|

| Mabel Seeley |

So, ironically, Seeley's career as a crime writer had just about peaked in 1941, the year Haycraft made his pronouncement.

Yet if she wasn't the "savior" of HIBK, Seeley was a highly-praised mystery author for a time.

Seeley's first novel, The Listening House, was seemingly universally raved; a dozen years later, Anthony Boucher called the book "one of the best of all first mystery novels." Her third novel, The Whispering Cup, he deemed "even more admirable" (indeed, Cup became Boucher's gold standard for Seeleys; when Eleven Came Back appeared in 1943 Boucher groused that the novel was slick but no Whispering Cup).

As a mystery author, Mabel Seeley in those years enjoyed not only uncommon critical, but also commercial, success. At a time when mystery novels averaged about 2000 sales per title (before the paperback revolution sales of mysteries mostly were confined to rental libraries), sales of Seeley's The Chuckling Fingers had topped 20,000 by October 1941, surpassing the total for Gypsy Rose Lee's The G-String Murders (see the Popular Library paperback cover illustration below too; I'm guessing this novel wasn't selling only to women in that incarnation).

This doesn't even consider the value surely accrued from serialization in glossy women's magazines, or "slicks" as Raymond Chandler derisively referred to them, a staple of such hugely successful HIBK writers as Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart (truthfully, the term "romantic suspense" might be a better one, but HIBK is what stuck).

One of the peculiar strengths that Mabel Seeley brings to her novels is the sort of plain, Middle American settings that she uses.

Where Rinehart and Eberhart tended to set their books in the abodes of the upper crust, Seeley elects more humble locales for her murderous mayhem (even The Chuckling Fingers, which deals with a moneyed family, stints readers of the trappings of great wealth). Seeley's heroines also hold "actual jobs," as academic Catherine Ross Nickerson puts it ("nurses, librarians and stenographers"), in contrast with the upper class spinsters and helpless ingenues we often see in the books of Rinehart and Eberhart (the latter women's respective nurse protagonists, Hilda Adams and Sarah Keate, excepted).

In The Chuckling Fingers, the protagonist, Ann Gay, comes to visit the Lake Superior shore home of her cousin, Jacqueline Heaton, recently married to Bill Heaton, a much beloved timber king (in contrast with his grandfather, Rufus Heaton, Bill is a conscientious capitalist, careful to responsibly harvest lumber and scrupulous and generous in his dealings with everyone).

|

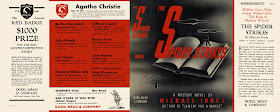

| She Walked in Horror and Fear (a--ahem!--striking cover) |

*(a family tree is provided, thank the Lord)

Could someone in the household be murderously insane? Or is a devious villain afoot, trying to make it look like someone is mad? These are the questions that Ann Gay asks herself as the pranks continue, and as, with deadly escalation, the dead bodies start to pile up, like cords of Minnesota wood.

But what the hey with that title, you may be asking, what does it mean? Well that's a good question. I give props to Seeley for coming up with a very odd'un. But it's easily explained. The Fingers are rock formations that resemble the digits of a hand and the "chuckling" is the noise made by the underground river below them. It's never quite as creepy as Seeley tries to make it, but it nevertheless makes for an interesting setting.

I liked the mystery plot here much better than that in The Crying Sisters, which The Chuckling Fingers resembles in some ways (in addition to the similar titles). Where the opening situation in Sisters struck me as extremely implausible (a supposedly levelheaded woman decides to go off to a remote lake resort with a surly man she has known for a couple of days and pretend to be his wife, all because she tales a liking to his young son), Fingers' Ann Gay behaves much more sensibly. Moreover, the narrative in Fingers is far less meandering.

|

| this jacket gives readers the fingers |

Near the end of the tale Ann and the man who obviously will become her future husband have no idea who the murderer is. In order to find out, they have to resort to a baiting a trap for the killer.

I eventually guessed who the fiend was and the motive (for the most part). However, I can't really say I deduced this, there not actually being the clues to allow one to do this (there are hints, but no more).

Still, Fingers is a good tale, with some clever elements.

I somewhat take issue with Catherine Ross Nickerson's presentation of Fingers as a feminist novel, however. Nickerson pointedly writes that in Fingers Ann Gay tries to help her "sister, not a boyfriend or husband" (actually it's her female cousin, not her sister).

Here Nickerson is advancing the idea of independent sisterhood, and I think there is merit in this view (Ann indeed is very committed to Jacqueline). Yet Nickerson does not mention that throughout much of the novel Ann Gay is collaborating in mystery investigation with a man, who clearly functions as her romantic interest.

Near the end of the novel, when Ann Gay is setting up her trap for the killer, her male friend arrives to take over: "He'd taken command," declares Ann happily, "and I saw the wisdom of his generalship." Hard to imagine those lines today! And the novel ends in the classical manner for this sub-genre: with the man and the woman locked in a passionate embrace and readers confident that they'll soon be hearing the peeling of wedding bells.

There's also this sentiment expressed at one point by Ann Gay, which seems to show that she subscribes to some extent to the idea of separate spheres for the sexes:

"Queerly I felt embarrassed, as if I'd looked at something I shouldn't see; the love one man can have for another is something no woman should ever look at."

It's important to remember that HIBK novels were, after all, genre books cut to a pattern, no matter how good individual ones might be. The idea that a protagonist, if young, attractive and female, might actually get killed--or, worse yet, be left single at the end of the novel--apparently was anathema to publishers, if not the authors themselves. To me, the knowledge that everything will always work out for the heroine in the end somewhat qualifies the "breathless suspense" that these novels always were said to have. It makes HIBK a kind of "cozy suspense," if you will.

However, the HIBK suspense novel would live on, into the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, as "psychological suspense" and "Gothic suspense" (anyone familiar with genre books will immediately recall, I'm sure, all those paperback Gothics in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with the beautiful women wandering at midnight in their nightgowns around the grounds of crumbling estates).

Books by Celia Fremlin and Ursula Curtiss, for example, were harder-edged, but still placed a premium on domestic suspense (I would say the harder edges made them more suspenseful). The early Ruth Rendell suspense novel Vanity Dies Hard (1965) is an exercise in HIBK devices (Rendell herself is now embarrassed by this book, but it's a fine, late example of the form). There's obviously something perennially appealing about HIBK, to men as well as women (whether the men admit or not). It's simply a form of suspense, and who doesn't like suspense?

|

| the Afton edition |

I prefer Hughes and Millar myself, but it's interesting to see a reader--and a male one at that (one who also read John Dickson Carr, Ellery Queen and Dashiell Hammett)--graduating from this one group of female suspense writers to the other as the decades passed. I'm sure he would have liked Mabel Seeley too! Plenty of male critics did.

Note: Four of Mabel Seeley's seven mysteries, including The Chuckling Fingers, are available in beautiful hardcover editions from Minnesota's Afton Historical Society Press. You just don't see this kind of deluxe treatment much anymore! These editions have especially fine dust jacket art--rather resembling WPA murals from the 1930s I think--by Paul S. Kramer.

.jpg)