Agatha Christie's accomplished biographers,

Janet Morgan and

Laura Thompson, were not particularly enamored with the Queen of Crime's second-string sleuthing duo, Tommy and Tuppence Beresford (both are single in their first appearance, 1922's

The Secret Adversary, but they have tied the knot when

Partners in Crime opens). Morgan deems them "

irritatingly perky," while Thompson goes farther yet, decrying them as "

appallingly twee."

But oh! aren't they just the cutest couple! To those of us who can appreciate the winsome charms of Tommy and Tuppence,

Partners in Crime--a new version of which will be airing on British television in 2015 (it has already been filmed once, back in 1983)--is a delectable confection of tales.

It's six years after the exciting events of

The Secret Adversary; and though Tommy and Tuppence still find married life blissful, it is sadly lacking when it comes to the thrills of crimesolving and spybusting. Happily for the bright young couple, they are offered the chance to take over a detective agency that is being used by the Soviets as some sort of intelligence gathering operation.

|

| After six years of marriage, life seems rather too tame |

Now Tommy and Tuppence can detect crimes and hunt spies again. What fun!

To aid them in the art of crime detection, the neophyte sleuths decide to imitate the great fictional masters, which gives Christie the chance to lightly parody some of her crime writing contemporaries (many of them forgotten today) and even herself. Yet more fun!

Although

Partners in Crime was first published in 1929, all but two of the stories were originally serialized in

The Sketch in 1924 (one story was published in

The Grand Magazine in 1923, while another did not appear until 1928, when it was published in

Holly Leaves, the annual Christmas special of the

Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News).

These Tommy and Tuppence tales followed two series about Hercule Poirot that were serialized in

The Sketch in 1923 and 1924. Some of these Poirot stories were collected in the volume

Poirot Investigates in 1924, while others Christie adapted as the novel

The Big Four in 1927.

Apparently the stories in

Partners in Crime are meant to take place in 1926, as the events in

The Secret Adversary take place, I believe, in 1920. However,

The Secret Adversary was published in January 1922 and the first of the

Partners stories in December 1923, so they in fact were only separated by about two years, not six.

I discuss the Tommy and Tuppence stories individually, as they appear in

Partners in Crime (their order in the book differs from the order in which they originally appeared in serial form). The original publication date is included in parenthesis, as well as the sleuth(s) parodied.

"A Fairy in the Flat"/"A Pot of Tea" (24 September 1924, as "Publicity")

"How prudent men are," sighed Tuppence. "Don't you ever have a wild secret yearning for romance--adventure--life?"

"What have

you been reading, Tuppence?"

"Think how exciting it would be," went on Tuppence, "if we heard a wild rapping at the door and went to open it and in staggered a dead man."

"If he was dead he wouldn't stagger," said Tommy critically.

"You know what I mean," said Tuppence. "They always stagger in just before they die and fall at your feet, just gasping out a few enigmatic words. 'The Spotted Leopard,' or something like that."

"

A Fairy in the Flat" sets the plot in motion, with Tommy and Tuppence getting hired by Mr. Carter, the government man from

The Secret Adversary, to take over Blunt's International Detective Agency.

This is a godsend to Tuppence, who, six years into marriage, is rather bored with her life. "

Twenty minutes' work after breakfast every morning keeps the flag [sic] going to perfection," she explains (I assume "flag" in the most recent HarperCollins edition should be "flat").

"I always like your cheery optimism, Tuppence. You seem to have no doubt whatever that you have talent to exercise."

"Of course," said Tuppence, opening her eyes wide.

"Yet you have no expert knowledge whatever."

"Well, I have read every detective novel that has been published in the last ten years."

"

A Pot of Tea" is an amusing trifle in which the resourceful Tuppence determines to find a cracking good case for Blunt's International Detective Agency. Tommy is masquerading as Mr. Theodore Blunt, the boss, Tuppence as his secretary, Miss Robinson, and the teenaged Albert (introduced in

Adversary) as the office boy.

The client in this case, the Wodehousian nitwit Lawrence St. Vincent (nephew and heir of the Earl of Cheriton, don't you know), will be referenced, along with his future wife, the shopgirl Janet Smith, in later tales (it seems they often tell their society friends what a wonderful job Blunt's did for them).

The Affair of the Pink Pearl (1 October 1924) (sleuths parodied, Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, R. Austin Freeman's Dr. Thorndyke)

"I'll tell you my idea of what we shall find at 'The Laurels,' said Tuppence, quite unmoved. "A household of snobs, very keen to move in the best society; the father, if there is a father, is sure to have a military title. The girl falls in with their way of life and despises herself for doing so."

Tommy and Tuppence are called in to to solve the case of Mrs. Hamilton Betts' missing pink pearl, which vanished at the Kingston Bruce's house party at The Laurels, Wimbledon. Reference is made to both Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Thorndyke, detectives who originally appeared in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, respectively.

For this case Tommy decides to go with Dr. Thorndyke, the great scientific detective, after his attempt at Holmesian deductions to impress the client fizzles miserably (his violin playing also is execrable).

Tommy has a new camera that he is just dying to use, and he thinks it will help him "do" Thorndyke.

Tuppence, however, is skeptical that her spouse can live up to the standard set by the Great Detective: "

I never heard that science was your strong point."

Tuppence is right. There really isn't much of Thorndyke to the case, even though Tommy does get to play around with the camera a bit.

It is an entertaining tale, however, with a decent plot and some nice shots taken at social snobbery.

"The Adventure of the Sinister Stranger" (22 October 1924, as The Case of the Sinister Stranger) (sleuths parodied, Valentine Williams' Desmond Oakwood, Sapper's Bulldog Drummond)

"Gott! What cowards are these English."

|

| a dangerous man to cross |

In this story, Tommy and Tuppence tangle with enemy spies who have tumbled on to their game.

The villain of the piece resembles

Valentine Williams' arch-fiend, Dr. Adolph Grundt ("Clubfoot"), so Tommy and Tuppence decide to model themselves after Clubfoot's opponents, Desmond Oakwood and his brother, Francis (as in the case of

Sax Rohmer's Dr. Fu-Manchu books, in Williams' Clubfoot series the over-the-top villain became the chief allurement).

Later Tommy decides their adversary is less like Clubfoot and more like Sapper's

Bulldog Drummond nemesis, Carl Peterson. Indeed, this is very like a Bulldog Drummond story with lots of action and not too cerebral a plot. Tommy even gets to call the villain a

swine.

Finessing the King/The Gentleman Dressed in Newspaper (8 October 1924) (sleuth parodied, Isabel Ostrander's Timothy McCarty)

"Be a sport, Tommy. Try to forget you're thirty-two and have got one grey hair in your left eyebrow."

Well, here we learn how old Tommy is! If the stories really do take place in 1926, then he would have been born around 1894 (this would make him around 26 in

The Secret Adversary, mid-forties in

N or M?, early seventies in

By the Pricking of My Thumbs and late-seventies in

Postern of Fate).

In an informative essay on

Partners in Crime,

Mike Grost says Christie does a good job parodying Timothy McCarty here. I wouldn't know personally, though I have at least one of his books. I have read one book by Isabel Ostrander but it did not have McCarty.

There is a murder in this tale, committed at the Ace of Spades, "

a queer little underground den in Chelsea," but it struck me as a rather simple affair. The upper class comes off rather badly in this one.

The Case of the Missing Lady (15 October 1924) (sleuth parodied, Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes)

As the visitor left the office, Tuppence grabbed the violin, and putting it in the cupboard turned the key in the lock.

"If you must be Sherlock Holmes," she observed, "I'll get you a nice little syringe and a bottle labeled cocaine, but for God's sake leave that violin alone."

An arctic explorer, recently returned to England, hires Tommy and Tuppence to find his missing fiancee. Tuppence declares that she is reminded of the Holmes case "

The Disappearance of Lady Carfax" (1911). The solution to the case (fairly clued and startlingly original to my knowledge) makes it one of my favorites in the collection.

Interestingly, the crime writer

Edgar Wallace (see more on him below) published a story, "

The Four Missing Merchants," in

The Strand Magazine in December 1929 that is similar in its plot to "

The Case of the Missing Lady," though Wallace puts an original twist on it. Had the Great Man read

Partners in Crime?

Blindman's Buff (26 November 1924) (sleuth parodied, Thornley Colton, the blind Problemist)

"One can't expect to be infallible straight away."

I have not read any of the adventures of the blind Problemist, Thornley Colton, but Mike Grost again assures us Christie does a good job with it. Even I, who have not read any Thornley Colton adventures, found Christie's writing about this detective and his assistant quite funny. Christie has to walk a fine line here, given the number of men who were blinded in the recent war (she has Tommy mention the war twice in this context).

There also is this comment, the book's most resounding sour note:

"The man two tables from us is a very wealthy profiteer, I fancy," said Tommy carelessly. "Jew, isn't he?"

The Great War "profiteer" who got rich from extortionate pricing of scarce and vital items while avoiding fighting on the lines was a stock figure in 1920s fiction. Often in English crime fiction he is portrayed as Jewish, clad in fur coat and flashy rings and speaking with a ridiculously exagerrated lisp.

This is another spy thriller story, with a resolution that resembles the one in a tale about another blind detective,

Ernest Bramah's Max Carrados.

"The Man in the Mist" (3 December 1924) (sleuth parodied, G. K. Chesterton's Father Brown)

|

ask a policeman

("The Man in the Mist") |

Christie has Tommy conveniently dressed as a priest, there's a commendable attempt at eerie atmosphere and the solution to the murder in the story is adapted from a very famous Father Brown tale. Yet this story in my view does not really capture the brilliant soul and richness of a Father Brown tale (a parody that conveys Father Brown very amusingly is

Leo Bruce's

Case with Three Detectives, 1936). Chesterton is a tough act to follow!

Not bad, but nowhere near my favorite in the collection. It has a perfunctory feel to it and the ending seems rushed.

The murder victim is a film actress, who is very stupid, Christie announces. This character reminded me of the actress character in the 1932 Miss Marple short story collection

The Thirteen Problems, except as I recall she turned out to be not quite so dumb after all.

"The Crackler" (19 November 1924, as The Affair of the Forged Notes) (sleuth parodied, Edgar Wallace's generic police detectives)

"Tuppence, we do need a larger office."

"Why?"

"The classics," said Tommy. "We need several hundred yards of extra bookshelf if Edgar Wallace is to be properly represented."

"We haven't had an Edgar Wallace case yet."

"I'm afraid we never shall," said Tommy. "If you notice he never does give the amateur sleuth much of a chance. It is all stern Scotland Yard kind of stuff...."

"I shall enjoy this case," said Tuppence. "Lots of night clubs and cocktails in it. I shall buy some eyelash-black tomorrow."

"Your eyelashes are black already," objected her husband.

"I could make them blacker," said Tuppence.

|

It is impossible not to be thrilled by Edgar Wallace

declared Wallace's English publisher--

and the English reading public seemed to agree

(Klaus Kinski starred in a series of

German Edgar Wallace films in the 1960s) |

Edgar Wallace, not Agatha Christie, was the bestselling English crime writer of the 1920s (he died in the United States in 1932 while working on the screenplay for

King Kong). As Tommy indicates, Wallace was also the most prolific English crime writer in the 1920s. In 1924 alone, he published six crime novels.

Christie's tale alluding to the king of the thriller puts Tommy and Tuppence on the trail of a gang of forgers passing their notes in London gaming society, but it is not nearly as exciting as a good Edgar Wallace tale. The best part is Tommy and Tuppence trying to get crook lingo straight (Wallace was considered an expert on such things; he even visited Chicago to study gangsters first-hand).

"

I always get mixed up between Busies and Noses," laments Tuppence.

|

The Great Man himself!

Edgar Wallace

(resembling a James Bond villain) |

I should add that Christie's title is brilliant. "The Crackler" is Tommy's nickname for the forgery gang boss they are after (banknotes "crackle," get it?). Wallace was known for his two word, three syllable book titles:

The Ringer (1926),

The Forger (1927),

The Squeaker (1927),

The Twister (1928),

The Gunner (1928),

The Terror (1929)--many of which he adapted into hugely popular London stage plays. You will notice that all these novels appeared after the serialized version of "

The Crackler" (called, prosaically, "

The Affair of the Forged Notes"). It seems clear that Christie came up with the better title after witnessing the appearance of all these additional Wallace books/plays, It makes me wonder how much Christie may have revised the stories for publication in book form.

"The Sunningdale Mystery" (29 October 1924, as The Sunninghall Mystery) (sleuth parodied, Baroness Orczy's The Man in the Corner)

"Of course," murmured Tommy, "I saw at once where the hitch in this particular case lay, and just where the police were going astray."

"Yes?" said Tuppence eagerly.

Tommy shook his head sadly.

"I wish I did. Tuppence, it's dead easy being the Old Man in the Corner up to a certain point. But the solution beats me. Who did murder the beggar?"

Mike Grost credits this story with being more than a surface parody, capturing both the form and style of Baroness Orzcy's Man in the Corner tales (mystery short story expert

Doug Greene tells me we should drop the "Old"), which are classics accounts of armchair detection.

Like Christie's recently published second Hercule Poirot novel, "

The Sunningdale Mystery" tells of a murder on the golf links. It is the most intricate tale in the collection, one that would have pleased Papa Poirot and thoroughly bamboozled Hastings.

Tommy and Tuppence solve the case through splendid teamwork, Tuppence supplying domestic psychology about the matter of choice of murder weapons (a hatpin in this case) and Tommy waxing wise about golf. As Tuppence reminds Tommy:

"And remember what [Inspector] Marriot once said about the amateur point of view--that it had the intimacy. We know something about people like Captain Sessle and his wife. We know what they're likely to do--and what they're not likely to do."

The House of Lurking Death (5 November 1924) (sleuth parodied, A. E. W. Mason's Inspector Hanaud)

"She's like those girls Mason writes about--you know, frightfully sympathetic, and beautiful, and distinctly intelligent without being too saucy, I think."

Tuppence reflected for a minute or two.

"I've got it," she announced. "Clearly he must have married a barmaid whilst at Oxford. Origins of the quarrel with his aunt. That explains everything."

"Then why not send the poisoned sweets to the barmaid?" suggested Tommy. "Much more practical."

This story with its splendidly lurid title tells of multiple poisoning murders at "

a great rambling old-fashioned house called Thurnly Grange."

There are four deaths and a rather melodramatic denouement, but then this is supposed to be Mason! It is fairly clued, although this is one of the cases where the culprit is rather too conveniently voluble with information.

I believe Mason's

The House of the Arrow, his first Hanaud mystery novel after a fourteen-year interval (

At the Villa Rose was published in 1910), appeared only shortly before "

The House of Lurking Death," but it certainly seems like Christie must have read it before she wrote this story.

A Hanaud short story, "T

he Affair at the Semiramis Hotel," also preceded "

The House of Lurking Death," in 1917.

"The Unbreakable Alibi" (December 1928, Holly Leaves) (sleuth parodied, Freeman Wills Crofts' Inspector French)

We were talking about detective stories. Una--that's her name--is just as keen about them as I am. We got talking about one in particular. It all hings on an alibi. Then we got talking about alibis and faking them."

"Inspector French, of course," said Tuppence. "He always does alibis. I know the exact procedure. We have to go over everything and check it. At first it will seem all right and then when we examine it more closely we shall find the flaw."

|

Tommy and Tuppence travelling by train

just like Freeman Wills Crofts' Inspector French |

Tommy and Tuppence are hired by wealthy young Montgomery Jones, yet another society nitwit. A young Australian woman, Una Drake--a detective fiction fan and "

simply one of the most sporting girls I ever met," says Jones--has promised Jones that she will wed him if he can break her alibi (I don't care what you say, I'm

sure this kind of thing happened

all the time in the madcap twenties).

Drake has provided evidence that she was in two locales, Torquay and London, at the same time. Jones--or actually Tommy and Tuppence--must determine which appearance she has faked.

Tuppence has read lots of books by Alibi King Freeman Wills Crofts and knows just what to do:

"We must get some other girls' photographs," said Tuppence.

"Why?"

"They always do," said Tuppence. "You show four or five to waiters and they pick out the right one."

"Do you think they do?" said Tommy--"pick out the right one, I mean."

"Well, they do in books."

The naive confidence of Tuppence notwithstanding, the bright young couple finds this a challenging task indeed. At one point Tommy pronounces: "

I am inclined to the theory of an astral body."

The solution is a (deliberate) letdown, putting this one very much in parody territory. Having written

Masters of the "Humdrum" Mystery, I have read everything by Crofts, and I think Christie's parody in this story is right on track, so to speak, and quite amusing.

It is odd that this story first appeared in print in 1928, four years after the previous one in the series and not long before

Partners in Crime was published. Was an additional story wanted for the collection, so that Christie wrote one more in 1928? Or had this tale been written back in 1923/24 with the rest and then set aside for some reason?

|

| Freeman Wills Crofts, probably thinking up another alibi |

By 1924,

Freeman Wills Crofts had published the landmark detective novel

The Cask and four other highly received mysteries, including

Inspector French's Greatest Case (1924), the first Inspector French novel, and was, along with Agatha Christie herself, one of the most popular "new wave" English detective novelists.

Inspector French himself would not have been the famous fictional figure in 1924 that he was in 1928, however, so I incline to the theory that Christie either wrote this story in 1928, or revised it then to specifically mention Inspector French. By 1928, Crofts had published three additional Inspector French detective novels:

Inspector French and the Cheyne Mystery (1926),

Inspector French and the Starvel Hollow Tragedy (1927) and

The Sea Mystery (1928).

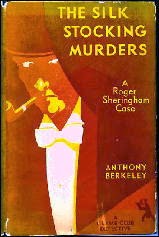

The Clergyman's Daughter/The Red House (December 1923, The Grand Magazine, as The First Wish) (sleuth parodied, Anthony Berkeley's Roger Sheringham)

"That's it," cried Tuppence. "We've got it! Solve the cryptogram and the treasure is ours--or rather Monica's."

Here is another story that Christie must have revised, if it really is true that it was originally published in 1923, because the detective parodied in it--he is mentioned by name--is Anthony Berkeley's Roger Sheringham, who did not even appear in an Anthony Berkeley novel (the author's first,

The Layton Court Mystery) until 1925.

By 1929, on the other hand, when

Partners in Crime was published, Berkeley had published three additional Sheringham detective novels, including

The Silk Stocking Murders, which shares similar elements with Agatha Christie's

The ABC Murders (Berkeley's celebrated

The Poisoned Chocolates Case would appear in 1929).

Was Agatha Christie that skilled parodist that she could parody a detective that the detective's creator had not yet created?!

Another reason that this story must have been substantially revised is that it appeared nearly a year before "

A Fairy in the Flat," the story that introduces the series' narrative "frame." Some enterprising person with access to the original sources, like

John Curran or

Tony Medawar,

really should check out this matter.

The story itself, a sort of treasure hunt tale, does not much resemble Anthony Berekely's Sherringham novels. The only real reference to Sheringham is that he likes to talk a great deal, so naturally the voluble Tuppence is the one who should "play" him..

This is certainly true, but Tuppence as Sheringham is not integrated into the story in any significant way. It is an enjoyable story, based on the familiar plot of faked ghosts being employed in an attempt to drive people out of their home (one might now call this the Scooby-Doo plot), but as a parody it is halfhearted as best.

The Ambassador's Boots (12 November 1924, as The Matter of the Ambassador's Boots) (sleuth parodied, H. C. Bailey's Reggie Fortune)

"Why are you being Reginald Fortune?"

""Well, really because I feel like a lot of hot butter."

This one is another rather weak parody, it seems to me, consisting of Tuppence occasionally mimicking foodie Reggie Fortune's supremely affected speech. Fortune had appeared in two H. C. Bailey short story collections before 1924 and in five by 1929. He was one of the most popular English sleuths in the Golden Age. The story, which deals with the question of why someone switched luggage with the American ambassador during his recent transatlantic voyage, is a good one.

The Man Who Was No. 16 (10 December 1924) (sleuth parodied, Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot)

"You comprehend, my friend?"

"Perfectly," said Tuppence. "You are the great Hercule Poirot."

"Exactly. No moustaches, but lots of grey cells."

"I've a feeling," said Tuppence, "that this particular adventure will be called the 'Triumph of Hastings.'"

|

| Will "Hastings" triumph this time? |

For the final tale in the collection, Christie parodies her own creation, Hercule Poirot, specifically referencing the Poirot stories published as

The Big Four. Matters with the Bolshevik spies are brought to a head in this tale; yet, despite the thriller elements, there is a very nicely plotted vanishing (Tuppence herself), in the classic Christie style.

Albert plays a bigger role in this one as well (he also has a funny bit with a lasso in the previous story). In fact, it is Albert who makes one of the most important implicitly feminist statements in the book, about the irrepressible nature of Tuppence:

"I don't believe anybody could put the Missus out, for good and all. You know what she is, sir, just like one of those rubber bones you buy for little dogs--guaranteed indestructible."

At the end of this tale, Tuppence announces that she and Tommy will soon be launching on a new, entirely different adventure. This adventure will take them out of commission from sleuthing fun until the outbreak of the Second World War, when they come back with a bang in

N or M? (1941).

Despite my

disappointment with the first Tommy and Tuppence book,

The Secret Adversary, I greatly admire

Partners in Crime.

I think that

Partners solidifies Tuppence's status in particular as an exceptional Golden Age sleuth and thriller character and that the stories themselves, while quite light for the most part, are consistently entertaining.

In short, like Tommy and Tuppence,

Partners in Crime is jolly good fun.