|

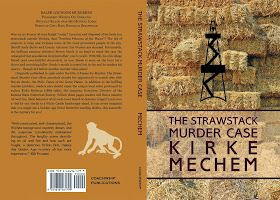

Raymond Chandler (1888-1959)

Chambers was no Chandler

but he is still worth reading |

2014 has been heralded as the 75th anniversary of a hard-boiled crime fiction milestone:

Raymond Chandler's first mystery novel,

The Big Sleep, which was published way back in 1939.

1939 also saw the publication of another first hard-boiled novel by a middle-aged American writer:

Some Day I'll Kill You, by

Dana Chambers, whose real name was the something less than hard-boiled Albert Leffingwell.

Kevin Burton Smith has expressed the view that a man with such a name as

Albert Leffingwell must be English, but this is not in fact the case.

Albert Fear Leffingwell (1895-1946) was the eldest son of two doctors:

Albert Tracy Leffingwell (1845-1916), a prominent social reformer, and

Elizabeth Fear Leffingwell (1864-1938), a pioneering woman gynecologist.

Albert Fear Leffingwell wrote admiringly about his parents in a short book dedicated to the memory of his brother, the ornithologist

Dana Jackson Leffingwell (1901-1930), who died of pneumonia before he reached the age of thirty:

Albert Leffingwell's book on "American Meat" shook Chicago long before racketeers were invented; his studies of the causes of illegitimacy in Great Britain were quoted in Parliament (once his intervention purely as an interested authority changed the whole course of English justice and saved a young mother from the gallows); his work in restriction of both human and animal vivisection probably achieved more than that of any other one person in the solution of that once-burning problem.

Elizabeth Fear--the young physician whom he married in 1892--was one of the first women in America to take a medical degree and to study in the great German clinics--at a time when the mere idea of Woman as anything but housewife and nursemaid excited either derision or alarm.

The daughter of Obediah Barnes Fear, an English Wesleyan Methodist who in 1850 migrated with his parents, wife and children to Pittson, a Pennsylvania coal mining town, Elizabeth Fear Leffingwell in addition to maintaining a successful medical practice home schooled her three sons at the sprawling Leffingwell abode on Cayuga Lake, at Aurora, New York, which the Leffingwells acquired in 1896, the year after their eldest son was born. Constructed in 1826 in the federal style and later remodeled according to the Italianate and Queen Anne fashions, the house, which still stands, is said to be the first brick building in Aurora.

Wanting her boys to experience Europe, Elizabeth took them on a tour of Bavaria and Italy the the spring of 1912 (this was right around the time of the Titanic disaster).

Dana Jackson Leffingwell received a doctorate from Cornell, while Albert Fear Leffingwell graduated from Harvard, in 1917.

The future hard-boiled writer early on showed literary inclinations, publishing a book of poetry,

Castles in Spain, while still at Harvard.

In 1925, he co-founded the advertising agency Olmstead, Perrin and Leffingwell, which four years later was absorbed by McCann (today the massive global advertising network McCann Erickson).

|

| the Leffingwell House at Aurora, New York |

Leffingwell did not publish his first crime novel until 1939, when he was 43 years old (this was also, incidentally, the year immediately following his mother's death).

Some Day I'll Kill You would be followed by twelve additional crime novels. All totaled, there appeared, between 1939 and 1947, ten books written under the pseudonym Dana Chambers, two under the pseudonym

Giles Jackson and one under the author's own name. Probably Leffingwell derived his most notable pseudonym from a Harvard dormitory building, completed shortly after he was born, called, yes,

Dana Chambers, that is now home to the offices of the Medieval Academy of America.

Leffingwell was praised in his day by no less than

Anthony Boucher and

Bill Pronzini has told me that he owns all the Leffingwell novels and has enjoyed his work.

In his

Saturday Review notice on

Some Day I'll Kill You (which appeared just one week after his notice on

The Big Sleep), "Judge Lynch" praised Dana Chambers for having "

lavishly overlaid" his "

antiquated plot nucleus" with "

rapid fire talk, brisk and bloody action, piquantly pulchritudinous females, and fervent drinking," rendering the verdict "

Lusty" on the novel.

This is a good summation.

Chambers' basic mystery plot design in

Some Day I'll Kill You definitely could come right out of an English country house detective novel. It is even set primarily at a house party in a country house, located near Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Several generations of Leffingwell ancestors hailed from this area. Albert Fear Leffingwell's great-great-great-great grandfather Thomas Leffingwell (1649-1723) started an inn at nearby Norwich, Connecticut in 1701 (it is a

house museum today).

|

| the Leffingwell Inn at Norwich, Connecticut |

Yet despite the novel's country house setting and the references to Sherlock Holmes we also have, as Judge Lynch indicated, booze, beatings, shootings, sexual byplay, beautiful women (four, to be precise) and criminal brutes, all presented to us in cool first-person narration by Jim Steele, surely

the toughest radio script writer ever.

I enjoyed it all immensely.

So here's the dope on the plot. Beautiful Lisa Ridgman calls on old beau Jim Steele, a writer of radio thrillers, to help her out of a jam. It seems someone is trying to put the squeeze on Lisa, claiming in anonymous letters knowledge that she murdered her first husband, Norman Barclay. This person will keep quiet for major hush money.

Lisa had a nervous breakdown not long after the death of Barclay in a mysterious fire on his yacht. She has since wed her psychiatrist, Mike Ridgman.

For Jim's part, after a madly passionate fling with Lisa (when she was in between husbands), he did a stint in the Spanish Civil War, fighting on behalf of the Republicans with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (had Leffingwell lived beyond 1946 to chronicle further adventures of his series sleuth into the Cold War, Jim's Spanish Civil War service might have made Jim a suspicious character to the American government).

|

life at the Ridgman country house doubtless is vastly

different from life at this Methodist church, built in 1805

in Timsbury, England, where Albert Fear Leffignwell's

maternal grandparents and great grandparents worshiped |

When Jim shows up with Lisa at the Ridgman house party near Old Lyme, he encounters:

- Mike Ridgman, Lisa's psychiatrist husband ("He wasn't my idea of a psychiatrist," says Jim, "he looked like a man who had captained the Princeton eleven in '05, say, and spent three decades since playing polo at Westbury.")

- Tommy and Marian Weston, a wealthy sportsman and his beautiful ex-actress wife

- Henry Allen, the Barclay family lawyer

- Mrs. Barclay, Norman's mother

- Marie Ridgman, Mike's nymphet half-sister

- Parker, the shifty English butler

Marian Weston dies that very night, from being fatally bludgeoned while taking a nap--i.e., passed out after too many highballs--on a porch swing.

Was someone after Marian, or could Marian have been mistaken for Lisa? Jim inclines to the latter supposition and he sets out to solve the mystery and save Lisa--even if she is, most inconveniently, married to another man.

There is a lot of action in this book. Our hero actually kills a bad guy, strangling him in Mike Hammer fashion (in his defense, however, it was, well, defense).

He also beats up a bad guy, shoots another bad guy in the face, kneecaps yet another bad guy and he gives serious thought to slugging an obnoxious cop.

Moreover, he gets sapped once by a bad guy and knocked out in a car crash. And not only does he never need to visit a hospital, he claims the second crack on the head actually jogged his brain, allowing him to reach the solution of the mystery.

If all this is not exciting enough for you, there's also a second murder (a shooting this time), a kidnapping and a massive explosion on the grounds of the Ridgman mansion (in his crime fiction Leffingwell had a great fondness for explosions).

Yet there's also some good byplay and nice little character studies to go along with all the mayhem.

Here's Steele talking to the soon-to-be late Marian Weston:

La Weston said: "But how is it you [Jim and Mike Ridgman] haven't met before?"

I said: "Oh, we don't move in the same circles. Dr. Ridgman cures the idle rich. I distract the idle poor."

"Sociologist?"

"No, radio scripts. I write half-hour thrillers. Sell toothpaste."

There's some nice sardonic description from Steele too:

Parker's great white ham-like face was beaded with perspiration as though he had been running. His features were clustered too close together in the middle of it, and I had a sudden irrelevant thought that he looked like Herbert Hoover.

There's quite a measure of sexual frankness in the book. Lisa tells Jim that her first husband, Norman Barclay, was a degenerate who sexually assaulted her that fateful night of the boat fire:

"

Norman was--he was--oh, skip it. He was a Krafft-Ebing case. I was unconscious and he--"

|

Undercover Work?

Jim and Louise |

There are some first class scenes between Jim and the manager of Lyme hotel, "

an aged Downeaster with steel-bowed spectacles and a face like a dried prune." He's a great little comic Yankee "character."

That's the old man's granddaughter, the luscious blonde Louise, in the great cover illustration to the Popular Library edition of the novel.

Louise provides Steele information on the shady roadhouse owner Maclay, as well as something of a third point on a love triangle.

Late in the novel Lisa gets jealous about Louise:

"What was all the blonde stuff?"

"One of my assistants. Undercover girl for Dr. Steele."

"I imagine she's quite good under covers."

Lisa is an interesting character in this book. She's smart and sexy and it's refreshing here, compared with so many traditional mysteries, to see a love interest who has been around the block several times, so to speak, and makes no apologies about it, nor is expected to.

How does it all get resolved? Does Jim crack the case? And, just as important, what happens with Jim and Lisa?

You will want to read on to find out. I certainly did.

Some other hard-boiled pieces at the Passing Tramp:

Murder with Pictures (1935), George Harmon Coxe

The Gentle Hangman (1950), James M. Fox

The Barbarous Coast (1956), by Ross Macdonald

The Ferguson Affair (1960), by Ross Macdonald

Detections and Tribulations:

Dashiell Hammett and

Bill Pronzini

Ray and Jimmy: Correspondence between Raymond Chandler and James M. Fox