Now the request is fulfilled by a generous collection: The Ordeal of Mrs Snow and Other Stories by Patrick Quentin. The title novelette is an almost too professional and neat exercise in suspense, but the eleven short stories are superlative. Many may be familiar to you from anthologies: still, they reread admirably, and seem even more impressive as a collected corpus. And now that these stories crime have at last been assembled, I have one further request: a comparison volume of the same team's equally skilled pure detective stories. (Note of complaint and correction: The publishers identify Patrick Quentin as "born Hugh Wheeler," and go on to a biography of Patrick Quentin, solo--which seems a marked injustice to the now retired Richard Webb, who created the pseudonym and was still an active collaborator when these stories were written.)

--Anthony Boucher review of The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow

Patrick Quentin produces a cool chill and a calculated thrill.

--Kirkus review of The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow

In the 1950s and 1960s Patrick Quentin, now inhabited solely by Hugh Wheeler (Richard Webb having left the partnership), was a much praised author of mystery and suspense fiction in the US and UK (as well as continental Europe), where he was lauded by such authorities as Anthony Boucher and Francis Iles (aka Anthony Berkeley Cox). Indeed, at this time Patrick Quentin was an accepted master of the sort of crime fiction which writer Sarah Weinman has vigorously publicized as "domestic suspense" (in its day usually more broadly characterized as "psychological suspense").

|

| with commendation from Mr. Iles |

Presumably on account of Patrick Quentin being a man (or two men, once) he was excluded from consideration for inclusion in Sara Weinman's 2013 noted short story anthology, Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense (see my review here). Yet several of these tales would be right at home there.

Besides being excellent suspense stories, many are self-revelatory works, drawing on details from the author's own lives, making them interesting on that level as well. The volume contains probably some of the most personal writings by these authors.

Original to this volume and one of the last pieces of crime fiction which Hugh Wheeler wrote, the title story, The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow is, as Anthony Boucher noted, a neat little suspense job that's almost too neat. Patrick Quentin didn't write for the slicks for nothing! When I read it I thought, this is just like an Alfred Hitchcock Presents episode (the hour long ones) and, sure enough, it appeared in 1964 in Season 2 of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow is about one of those popular types of 20th century crime fiction, the wealthy widowed (or never married) aunt, in this case an "old lady" of sixty (just a decade older than the author), whose suspicion that gorgeous Bruce Mendham, the husband of her beloved niece, Lorna (played by Jessica Walter in the television version), is nothing but a gold digger is confirmed when she finds that he has been brazenly forging checks in her name.

When she confronts Bruce with the evidence he locks her in her vault safe to die. Conveniently for Bruce, he and Lorna are going away to the Long Island coast for the Labor Day weekend, so Bruce figures he's got it all taped. But can resourceful "Aunt Addy" outwit the ruthless gigolo in the end? This one includes some sailing detail (read it and see), drawing on Rickie and Hugh's experiences in the Caribbean.

The locked-in-the-vault plot actually occurs in another, earlier story in the collection, but Mrs. Snow is a slick little number even when wearing something slightly shop-soiled. The next ten stories are:

A Boy's Will

Portrait of a Murderer

Little Boy Lost

Witness for the Prosecution

The Pigeon-Woman

All the Way to the Moon

Mother, May I Go Out to Swim?

Thou Lord Seest Me

Mrs. Appleby's Bear

Love Comes to Miss Lucy

This Will Kill You

The first four stories all crucially involve young children or adolescents with murder. "Naughty youngsters all over," is how the Saturday Review put it, evincing, like Anthony Boucher, a certain touch of cynicism about the innate goodness of human nature. Today one might be reminded of some of Patricia Highsmith's essays in this arena. In A Boy's Will, American expat John Godolphin not long after the Second World War encounters in Italy one Sebastiano, a Palermo street urchin "who could not have been more than fourteen....watching him from unblinking dark eyes, soft as wallflower petals. The sturdy, honey-brown body was scantily covered by a tattered G.I. T-shirt and a pair of faded blue shorts. A hand was stretched out--dirty, broken-nailed, quivering with hope."

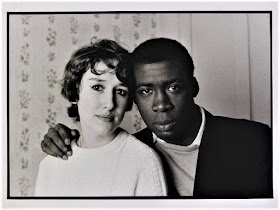

|

| John Godolphin spent the morning studying Byzantine mosaics in the churches of Palermo before he encountered his secular "angel," Sebastiano |

Its appearance in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine in June 1950 somewhat hamstrings this story about a predator--in this instance a highly predatory Italian youth. Does John Godolphin worship "Beauty" in some lofty aesthetic way or is he simply attracted to beautiful Italian youths? I thought his character too innocent to be believed, whatever 1950 readers of EQMM may have thought.

Although the story elides sexual implications, it is obviously drawing on Thomas Mann's famous novella Death in Venice (1912) and in a queer case of coincidence it actually preceded by a few months Tennessee Williams' The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, a novella about a middle-aged American widow who while traveling in Italy becomes a client of a much younger male hustler. The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, incidentally, was adapted in 1961 into a film directed by Jose Quintero, who the same year directed Hugh Wheeler's second stage play, Look, We've Come Through. Hugh probably wrote similarly-titled The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow that same year. Coincidence?

|

| Need a light? Vivian Leigh as the title character in The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone |

That's some big names to throw around, but unfortunately, I thought that A Boy's Will, which with cruel irony recalls the lines from a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem--"A boy's will is the wind's will/And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts"--only skimmed surfaces for shock value. Rickie and Hugh did make at least one trip to southern Italy, in 1947 (around the same time as Tennessee Williams). Hugh also would write about Italy in a 1951 solo novel, The Crippled Muse, which he dedicated to Rickie and published in his own name.

Better than A Boy's Will, I thought, is Portrait of a Murderer, originally published in Harper's Magazine in 1942. It's a strange, sardonic and dark story of an English schoolboy driven to the ultimate sin by his loathsomely unctuous and controlling father. It's another story suffused with sexual undercurrents. (There's sadism and--it seems strongly implied to me, at least--molestation of a child by a father.) Both Rickie and Hugh were graduates of English public schools and they knew that world, so alien and strange to so many of us today (though this feels more like a Rickie story to me).

|

| Afternoon of a Faun Vaslav Nijinsky |

Next is another child-centered tale, Witness for the Prosecution, which is narrated by an eleven-year-old girl who is the key witness in a murder case. This is one which would have made a good inclusion in Sarah Weinman's book, in my view. The Pigeon-Woman involves a waitress with a heart of gold, a developmentally challenged man, some pigeons and, oh yes, a maniac killer. I wasn't quite persuaded by this one, which gets a little stickily sentimental, uncharacteristically for the author.

All the Way to the Moon tells the story of a business executive who wants to get rid of his invalid wife so he can relocate to Mexico, a country symbolizing ultimate freedom to him. It probably won't surprise you to hear that Hugh Wheeler regularly vacationed in Mexico. This one has a nice little alibi trick, but will it hold?

|

| I don't like that look in his eyes.... William Shatner in Mother, May I Go Out to Swim? See William Shatner's Toupee |

By the way, has anyone ever explored William Shatner's rather impressive pre-Star Trek contribution to suspense anthology television? Ah, here's one! Also see my take on a Shatner genre performance here.

Next is Thou Lord Seest Me, about mild Mr. Loomis (or as little girls know him, "Daddy Bloomers"), a middle-aged English clerk with a horrid wife of the nature that used to get dubbed "castrating." All poor Daddy Bloomers wants is just to be left alone to spend more time with sweet little girls....This story, which originally appeared in EQMM in 1949, gets seriously creepy. Even though things are never explicitly called out by their names, the message definitely gets across.

Perhaps a story about a middle-aged man chasing after young girls was more acceptable to the mid-century EQMM reading public than one about a middle-aged man chasing after young boys. "Daddy Bloomers" is particularly obsessed with a photo of one of the secretaries in his company taken when she was a child, which he has purloined as a a sort of memento: "barelegged little Rosie Henderson at the age of eight, happily sucking a stick of candy rock on the sands of Burnham-on-Sea" (Rickie's home town again recollected). I found this a far more unsettling story than the somewhat synthetic and slick A Boy's Will.

Next there's the other original story to the volume, Mrs. Appleby's Bear, a mordant tale about a tyrannical, elderly, wealthy invalid aunt and her two rather resentfully dependent middle-aged nieces. Very much a case of malice domestic, and very much a good one, even if Hugh snitched the murder method which he and Rickie had used in their 1945 Jonathan Stagge novel Death and the Dear Girls. It was worth the snitch, however.

The last-placed story in the collection is This Will Kill You, a dark comedy of death about a husband, a retail druggist, who keeps trying, and failing, to kill his much-loathed wife. I'm surprised Hitch's TV series never got around to doing this one. Rickie's background as a pharmaceutical executive is drawn upon profitably.

I think it's the penultimate story, however, that is the brightest gem in the collection, the Hope Diamond of the volume let us say. It is Love Comes to Miss Lucy, originally published in EQMM in 1947. At the risk of overselling (something I was accused of doing in my last blog article), I have to say this is one of the best crime stories I have read. (Now I've done it!) Every detail fits into place perfectly. It's another Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone-ish story, but the conviction here feels stronger, perhaps because of the fact that it's dealing with a heterosexual relationship rather than a homosexual one, allowing Hugh freer reign to explore sexuality and passion.

The story concerns a wealthy spinsterish middle-aged American tourist, Lucy Bram, who with two lady companions travels to Taxco, Mexico. "They looked exactly what they were," we are told in the opening paragraph, "three middle-aged ladies from the most respectable suburbs of Philadelphia."

|

| "the fantastic Churrigueresque altar of gold-leaf flowers and cherubs gleamed richly back at her" Church of Santa Prisca, Taxco |

This is both a clever story and a poignantly ironic one, giving rise not only to speculations about sexuality and the complexity of human connection, but the impact of American and European colonialism in the developing world. It's also easy to discern, like in the work of Tennessee Williams, gay subtext. Around this time Hugh himself, like Tennessee Williams, had a relationship with a handsome young man from Mexico; so in this case he directly knew of what he wrote, and I think it shows. Additionally, Miss Lucy's background recalls that of privileged women he would have known in Philadelphia.

Love Comes to Miss Lucy was adapted for the American television series Danger in 1951, although it never appeared on Alfred Hitchcock Presents or The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. However, it was included in the Alfred Hitchcock print anthology Stories They Wouldn't Let Me Do on TV. Was that just a tease for a book? Perhaps not; some of the stories in The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow push the envelope by the standards of the 1950s, though Love Comes to Miss Lucy was previously aired on Danger. I'd be interested to see that adaptation.

In his assessment of the fiction of Patrick Quentin, whom he treated as one of the more notable crime writers of the period, English crime writer and critic Julian Symons contended that "The books don't dig quite deep enough to be called serious crime novels, but all are alert studies of people who commit crimes for plausible reasons. On their own level these stories are credible, where a book like [Ellery Queen's] Ten Day's Wonder is not." Whether one agrees with Symons' assessment entirely or not, I think some of the stories in The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow are "serious crime stories"--and notable ones at that.

Note: The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow will be reissued this August by Mysterious Press/Open Road, making it the first time it has seen print in a half-century. As for the "equally skilled pure detective stories" by Patrick Quentin which Anthony Boucher mentions in his review, expect to be seeing those soon!