The Eighties saw the demise, finally, not of the Golden Age of detective fiction, which had ended long previously, but of almost the entire Golden Age generation itself. The Golden Agers had long entered their golden years, as it were, and increasingly they were shuffling off their mortal coils. Erle Stanley Gardner died in 1970, the cousins who comprised Ellery Queen, Manfred Lee and Frederic Dannay, in 1971 and 1982, Nicholas Blake in 1972, Christopher Bush and Anthony Gilbert in 1973, Rex Stout in 1975, Agatha Christie in 1976, John Dickson Carr in 1977, Ngaio Marsh in 1982, Gladys Mitchell in 1983, Hugh Wheeler, still a comparative youngster at 75, in 1987 and Michael Innes, belatedly at the age of 88, in 1994.

The list of genuine Golden Ager mysteries from the 1980s is thin indeed, but would definitely include these titles:

NGAIO MARSH

Photo Finish (1980)

Light Thickens (1982)

GLADYS MITCHELL

Uncoffin'd Clay (1980)

The Whispering Knights (1980)

The Death-Cap Dancers (1981)

Lovers, Make Moan (1981)

Here Lies Gloria Mundy (1982)

Death of a Burrowing Mole (1982)

The Greenstone Giffins (1983)

Cold, Lone and Still (1983)

No Winding Sheet (1984)

The Crozier Pharaohs (1984)

MICHAEL INNES

Going It Alone (1980)

Lord Mullion's Secret (1981)

Sheiks and Adders (1982)

Appleby and Honeybath (1983)

Carson's Conspiracy (1984)

Appleby and the Ospreys (1986)

Michael Innes was no piker here (Marsh's writing stride was ended for good by her death in 1982), producing six books between 1980 and his retirement in 1986 (I believe he was suffering from Parkinson's Disease), but Gladys Mitchell gave us ten volumes between 1980 and 1984! Indeed, she was so prolific at this time that at her death at the age of 82 on July 27, 1983 she left behind three complete Mrs. Bradley mysteries, which became her final published novels. The last of these, The Crozier Pharaohs, was received by her English publisher just two weeks before she died.

So it would seem that among the remaining Golden Agers it was Gladys Mitchell who was doing the most to keep the classic detective novel alive.

Several of Michael Innes' late books, it must be admitted, aren't even really classic-form detective novels at all and would be a disappointment to those expecting such. But how good are the later Gladys Mitchells, all of them written when the author was between the ages of 79 and 82? To be honest, it's rather a mixed bag. I can't abide Lovers, Make Moan (1981), for example. But one of the high points, in my view, is her novel Here Lies Gloria Mundy, her 61st of 66 Mrs. Bradley detective novels.

Gloria Mundy has a lot of similar features to other late Mitchells, to be sure. It anachronistically reads, on the whole, like it was written in the 1930s, in terms of character speech and setting. There is even a rhetorical attempt to pin the crime on a "passing tramp"! (Hurrah!)

|

| Down at our rendezvous...Three's company too! |

The lead character and narrator, Corin Stratford, a freelance writer and novelist (a common lead character type in late Mitchell), talks like someone out of Thirties detective novel, except when he very occasionally throws out some ill-advised Swinging Seventies slang like "pad," referring to the place he lives.

Were people still saying pad in that sense in 1982, during the early Reagan-Thatcher era? They sure weren't where I lived. I don't even think they were saying it on the TV series Three's Company, when the gang trooped down to swing at the Regal Beagle.

So too talk Corin's pals Hardie Keir McMaster, a old public schoolmate egregiously nicknamed "Hara-kiri," and Anthony Wotton, owner of the lovely ancestral country manor Beeches Lawn in the Cotswolds.

Why, there's even a house party at Beeches Lawn, which is pretty fully staffed with servants--maids in caps, cook, gardener and boy, though a butler is not in evidence--who say mum and master and the like and get agitated and disordered when there's murders and such on the premises. Really, it does quite take one back to the good old days!

Another characteristically Gladysian feature is that everyone in this novel seemingly loves nothing more in life than tramping about old churches and barrows and whatnot and discussing the intricacies of medieval architecture. There's more architecture in this book than there is a PD James novel, although in Mitchell it's not so long-windingly described as in James, thankfully.

I'd also say that with a couple of exceptions Gloria Mundy is a pretty phallocentric novel, in that women, including the title character, are most often seen through male eyes, especially those of the narrator. The exceptions are a couple of elderly ladies: perennial series sleuth Mrs. Bradley, aka Dame Beatrice, who actually doesn't appear in the novel that much, sadly (her sidekick Laura is in it even less, happily); and a wonderful cracked old woman with a witchcraft obsession, Miss Eglantine Brockworth, the great-aunt of Anthony Wotton's wife Celia.

The novel opens with Corin running into "Hara-kiri" at an old church, naturally enough (at least for a Gladys Mitchell novel).

McMaster is out collecting gravestone epitaphs (but naturally!), while Corin want to see the sheila-ma-gig. Um, sheila-me-what? "She's a rather rude lady who appears on some Irish churches," Corin explains. "My guess is that she represents something fairly unspeakable from the Book of Revelations."

But wait, this isn't just self-indulgent decorative matter, because, as we shall see, our good Glad is foreshadowing! In a review article on Gloria Mundy and her creator in which he highly praised "The Great Gladys," English poet Philip Larkin remarked that he enjoyed rereading Mitchell's detective novels purely as novels; and her best work does have something of the quality of good mainstream novels, even when the mysteries go somewhat awry.

In this one the mystery is pretty good, however. Mitchell's never going to have the supreme clarity of a Christie or Crofts, but it the plot here hangs together fairly well. (Would the police really have arrested that guy though?) Still, the most enticing part of the mystery is found in the author's dabbling with the witchcraft theme.

The title character, Gloria Mundy, is this waif-like creature with parti-colored head of red and black who has a most bewitching effect on the men around her, including both McMaster and Anthony Wotton, with whom she had flings which ended badly. Gloria actually is descended, apparently, from a former mistress of an ancestor of Anthony's at Beeches Lawn, a strange woman who had the same red and black hair and is said to have been a witch.

There's a striking nude portrait of this woman from the past hanging in a small house on the grounds of the estate, which the master of Beeches Lawn had built for his mistress. Is Gloria a reincarnation of this woman? Is she a witch too? Great-Aunt Eglantine sure thinks so--and, as she never tires of telling people, she has read the Malleus Maleficarum! She also identifies Dame Beatrice as a white witch, by the by, which I would readily believe.

Not only may Gloria Mundy be a witch, she might be a murderess--or a murder victim--or even a ghost. Or perhaps all of the above!

By all means read the book and see for yourself. John Dickson Carr fans may be reminded of Carr's novel The Burning Court (1937), one of the classics of the Golden Age of detective fiction. One might wish that Mitchell had written Gloria Mundy back in the Thirties, when she, like Carr, was at her peak as a writer, but the book still strikes me as quite effective indeed. One American reviewer called it "bizarre, sexy, unsettling." Certainly the final chapter of the novel is quite exceptionally eerie and as intriguing as anything in the Mitchell oeuvre.

As for sexiness, there is, as Philip Larkin noted, actual sex in this novel (apparently), when a virginal good girl canoodles with Corin. They are planning to get married though, so rest assured censorious readers! All through the novel Mitchell conveys the sexual appeal of women for men quite convincingly, though not so much the other way round.

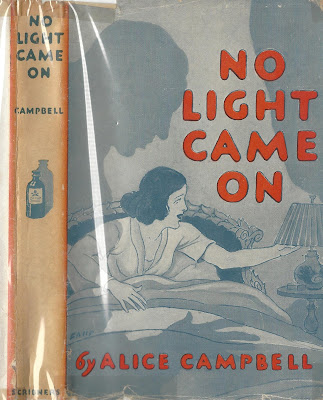

Both sexiness and eeriness are effectively conveyed on the novel's wonderfully weird and sexy dust jacket design, featuring the bare-breasted title character (see first pic above), for which Mitchell actually felt compelled to apologize when she sent an autographed copy to her sister, a nun, explaining abashedly that she didn't choose the cover art!

.jpg) |

| Gee, thanks, but you really shouldn't have! |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)