|

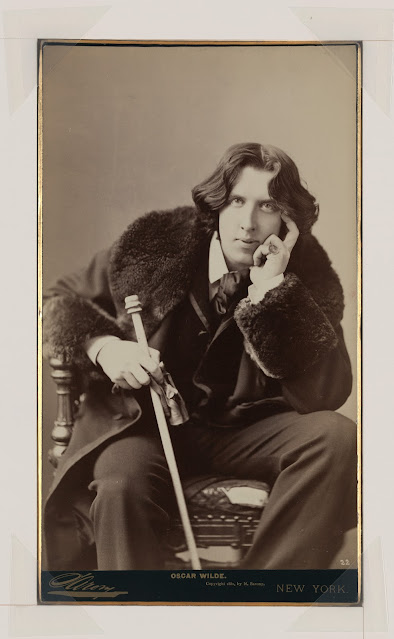

He said what?

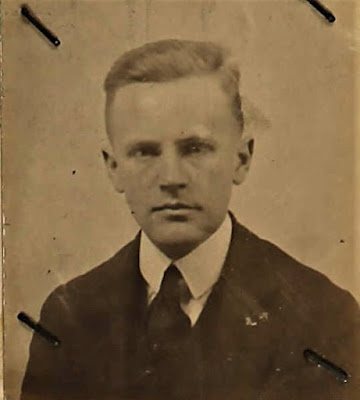

British crime writer and critic

Julian Symons (1912-1994) |

Most

of the generation of writers that produced the Golden Age of detective fiction,

that brief era when the puzzle plot purportedly reigned supreme, had departed

not only from the field but from life itself when, a half-century ago in the

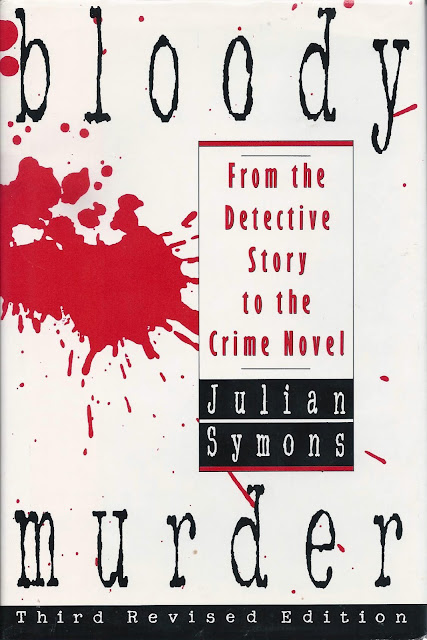

Spring of 1972, British crime writer and critic Julian Symons published Bloody Murder, his landmark study of

mystery, detective and crime fiction--there is a difference among them, to be

sure--and the first survey of the murder and misdeeds genre since Howard

Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure: The Life

and Times of the Detective Story, published three decades earlier in

1941. What made Bloody Murder significant in a way that Haycraft’s book, notable as

it was, had never been, is indicated by Symon’ subtitle, From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel. As one of the contemporary reviewers of Bloody Murder put it:

[Symons]

accepts that fiction’s criminal records are primarily entertainments but

contends that inside this limit there is a point at which escapist and serious

writing converge. He defines this as the

crime novel. Here, puzzles take second

place to characterisation: the concern is not with murder but its consequences

and it is not simply man who is indicted but society itself….Not everyone will

accept the thesis—the diehards will insist that the puzzle is all—but few will

be able to resist the cause.

In writing Bloody Murder, Julian Symons wanted to isolate and quarantine from

the crime novel the “frivolous” but infectiously entertaining detective story,

which in his view had for too long hampered, if not prevented, the genre from

being taken, and taking itself, seriously.

By his own admission Symons wanted both practitioners and public alike to

appreciate that “[i]n the highest reaches of the crime novel, it is possible to

create works of [literary] art,” if admittedly ones “of a slightly flawed kind”

on account of their intrinsic dependence on “sensationalism,” which went back

to the crime novel’s roots in the days of the Victorian sensation novel. Even in superior crime novelists, Symons

avowed, there still was something “that demands the puzzle element in a book,

or at least the element of uncertainty and suspense, as a diabetic demands

insulin.” Symons did not say, as the

consciously highbrow mystery-hating critic Edmund Wilson doubtlessly would

have, “as a drug addict needs a fix,” although it actually would have been a

more accurate expression of the point which Symons was making: that there was

something slightly seamy in all forms of fictional mystery mongering.

1972 seemed a propitious year indeed

for finally putting the “detective story” back in its proper place as mere

entertainment and apotheosizing the serious novel of crime (note that Symons

does not dignify the “detective story” with the word “novel”), as the

generation which had produced so many prime specimens of the detective novel--I will use the word novel--was passing

from the world’s mortal scene. The

review of Bloody Murder quoted above,

which appeared in the pages of The

Guardian on April 6, 1972, came from the hand of Matthew Coady, successor

in the “Criminal Records” crime fiction review column to Anthony Berkeley

(under his pen name Francis Iles), who had died just a little over a year

earlier, on March 9, 1971. Along with

Agatha Christie, who would pass away less than five years later on January 12,

1976, Berkeley had been all that remained on earth of the original founders of

the Detection Club, started in London in 1930 as a social club for eminent

practitioners of the fine art of clued murder, as opposed to the purveyors of

mere thrills, or the shocker-schlockers, if you will, inheritors of the lowly

penny dreadful tradition, like Edgar Wallace, “Sapper” and Sax Rohmer.

Then pushing eighty years of age,

Anthony Berkeley had steadfastly remained in the reviewing saddle throughout

most of 1970. On October 15 he submitted

his final column, which included a review of one of Agatha Christie’s last and

least novels, a muddled political thriller, or something, titled Passenger to Frankfurt. About the lamentable Frankfurt Berkeley had little on point to say (What could one in

kindness say?), aside from an unintentionally amusing and characteristically

cranky bit of carping: “Of all the idiotic conventions attached to the thriller

the silliest is the idea that a car whizzing around a corner at high speed can

be aimed at an intended victim who has, quite unseen, stepped off the pavement

into the roadway at exactly the right moment.

Mrs. Agatha Christie uses this twice in Passenger to Frankfurt.” One

can almost hear that final triumphant Harrumph!

Agatha Christie happily enjoyed a

brief Indian summer the next year with her goodish, if by no means great, Miss

Marple detective novel Nemesis, but

she then published two more mysteries, Elephants

Can Remember (1972) and Postern of Fate

(1973), which were remarkable only as indicators of the author’s rapidly

diminishing powers. Anthony Berkeley

himself had not published a mystery novel in over three decades, having

contented himself with reviewing them under his Francis Iles pseudonym. While there were still a few old timers

around plying the clued murder trade with evident zest, like Ngaio Marsh,

Michael Innes and Gladys Mitchell, their ranks were sadly diminished, like

those of Great War veterans at an Armistice Day commemoration. Even Edmund Crispin, for a few brief years

after the war the wunderkind of detective fiction but now an alcoholic walking dead

man, struggled, zombie-like, for over a decade to complete a final mystery

before his tragic, untimely demise in 1978 at the age of fifty-six.

Julian Symons was well aware of all the

death and decline going on around him.

He began writing Bloody Murder in

1970 at the relatively youthful age of fifty-eight, after having retired from a

decade-long stint as the crime fiction reviewer for the Sunday Times. (His

replacement had been his philosophical opposite Edmund Crispin.) In his critical magnum opus, which he

completed the following year, he predicted

this dire fate for the future of the “detective story”: “A declining

market. Some detective stories will

continue to be written, but as the old masters and mistresses fade away, fewer

and fewer of them will be pleasing to lovers of the Golden Age.”

Symons

omitted from his study any mention of rising British murder mistresses P. D.

James, Ruth Rendell, Patricia Moyes, Catherine Aird and Anne Morice, all of whom

wrote mysteries in the classic puzzler vein and were more than acceptable to

“lovers of the Golden Age.” (Morice, long

out-of-print, was republished last year by Dean Street Press.) The Seventies in fact would see continued

success for all five of these authors, particularly James and Rendell, and

additional notable practitioners of detective fiction joined the murder muster

during the decade, like masters Peter Lovesey and Reginald Hill, both of whom

actually had published their first detective novels in 1970, and masters Colin

Dexter, Robert Barnard and Simon Brett, who came along but a few years later. By 1992 a now octogenarian Symons, who was

just a couple of years away from his own death, was still doggedly insisting

that the market for the detective story “has declined,” although face savingly

he added, albeit somewhat confusingly, that “few old-fashioned detective

stories are written.” Did he mean books

with country houses, men-about-town, stately butlers, terrified maids, bodies

in libraries and other such impedimenta?

Writers like P. D. James and Ruth Rendell hardly had need of those to

devise classic detective fiction.

Yet

“A Postscript for the Nineties,” the valedictory chapter of the third edition

of Bloody Murder, was filled with the

author’s grim foreboding for crime writing’s future. In it Symons lamented the sadistic violence

of James Ellroy's “strip-cartoon” neo-noir tales like L. A. Confidential (1990) and Thomas Harris’ gruesome serial killer

novel The Silence of the Lambs (1989)

(“the literary equivalent of a video-nasty”), as well as the startling,

disturbing rise of…the criminal cozy. Seemingly contradicting his prior claim in

the same volume that the detective story market had declined, Symons acknowledged,

with a certain sense of rue, that the previous reports (mostly his) of the

death of detective fiction had in fact been grossly exaggerated, especially in

his native country, as evidenced by the success of what he called the cozy

mystery (referencing the founding of Malice Domestic in the United States in 1989),

which he conflated with puzzle-oriented detective fiction:

In Britain the cosy crime story still

flourishes, as it does nowhere else in the world. We are a long way away from the fairy-tale

crime world of Agatha Christie, but a large percentage of the mystery stories

in Britain are deliberately flippant about crimes and their outcome….it would

seem that the British crime story has always been marked by its lighthearted

approach, from the easy jokiness of [E. C. Bentley’s] Philip Trent through the

elaborate fancifulness of Michael Innes and Edward [sic] Crispin to the show

businesses mysteries of Simon Brett. A similar refusal to

be serious about anything except the detective and the puzzle can be found on

the distaff side in a line running from Patricia Wentworth through Margery

Allingham and Christianna Brand to half a dozen current exponents of crime as

light comedy. This is a product for which there is still a steady demand, as

the recent foundation in the United States of a club for the preservation of

the Cosy Crime Story shows.

Symons

attempted to distinguish James, Rendell, Lovesey and Hill, long leading lights

in what might be termed the Silver Age of detective fiction, from their Golden

Age forbears, praising their more “serious” crime novels, like James’ A Taste for Death (1986), where the murderer

is revealed two-thirds of the way through the novel. But the truth is these authors wrote

plenteous puzzle-oriented detective fiction (embroidered, to be sure, with

lively characterization and social observation), just like their forbears from

the Golden Age did. Today of the

aforementioned quartet only Peter Lovesey, now himself an octogenarian, is

still alive and active, yet younger writers have carried on with the writing of

detective fiction in the classic vein, which has now achieved a popular and

critical cachet that it has not enjoyed since the Golden Age itself. New reprints of Golden Age mysteries, many by

authors long out-of-print and forgotten, appear every month. It becomes more obvious with each passing

year that Julian Symons greatly underestimated the public’s passion for “mere puzzles.”

The

dismissiveness which Julian Symons in Bloody

Murder expresses toward many prominent writers of vintage detective fiction

might startle those unfamiliar with his writing (and perhaps some of those who

think they are familiar with it.) His

animadversion against those detective writers, like Freeman Wills Crofts, John

Street and Henry Wade, whom he notoriously termed “Humdrum” is well-known and I

have written about this at length in my 2012 book Masters of the “Humdrum” Mystery, so I will not go into that again

here. Here I want to look at Symons’

disparagement of other Golden Age greats, beginning with one of the towering

figures of the era, Dorothy L. Sayers, whom, in the first edition of Bloody Murder, Symons repeatedly disrespects,

as I am sure Sayers herself would have seen it, by omitting the “L.” from her

name. (The “L.” is restored in the third

edition.) Symons likes Agatha Christie--though

he declares that she was not a good writer from a literary standpoint and that her

fictive world was a “fairyland”-- as well as John Dickson Carr, Ellery Queen, Anthony

Berkeley (primarily on account of his Francis Iles crime novels), and even S. S.

Van Dine, creator of the extraordinarily obnoxious amateur sleuth Philo Vance;

yet when it comes to Dorothy L. Sayers he is positively withering in his

assessment:

There can be no doubt that by any

reasonable standards applied to writing, as distinct from plotting, she is pompous

and boring. Every book contains enormous

amounts of padding, in the form of conversations which, although they may have

a distinct connection with the plot, are spread over a dozen pages where the

point could be covered in as many lines.

This might be forgivable if what was said had some intrinsic interest,

but these dialogues are carried on between stereotyped figures…who have nothing

at all to say, but only a veiled clue to communicate….[Lord Peter Wimsey] is a caricature

of an English aristocrat conceived with an immensely snobbish, loving

seriousness….[His knowledge is] asserted rather than demonstrated, and when

demonstration is attempted it is sometimes wrong….Add to this the casual

anti-Semitism…and you have a portrait of what might be thought an unattractive

character. It should be added that many

women readers adore him….[Her later novels] show, with the exception of the

lively Murder Must Advertise, an

increasing pretentiousness, a dismal sentimentality, and a slackening of the

close plotting that had been her chief virtue.

Gaudy Night is essentially a

“woman’s novel” full of the most tedious pseudo-serious chat between characters

that goes on for page after page.

Altogether

more gently (the Sayers stuff is so edged as to seem personal), Margery

Allingham is faulted for not retiring Campion to the home for superannuated

aristocrat sleuths (her books “would have been better still without the

presence of the detective who belonged to an earlier time and a different

tradition”), while Ngaio Marsh is taken to task for seeking “refuge from [the

depiction of] real emotional problems in the official investigation and

interrogation of suspects,” with Symons adding chidingly that “one is bound to

regret that she did not take her fine talent more seriously.” He is even more critical of Josephine Tey,

long boosted by her many fans as something really new in crime fiction and the

Fifth Crime Queen (Christie, Sayers, Allinhgam, Marsh, and sometimes Tey), whom

he summarily dismisses as belonging to

the past and “really rather dull,” along with Ellis Peters, author of the

beloved Brother Cadfael mysteries (“I have tried three books without getting to

the end of one”), Gladys Mitchell, currently undergoing a revival (“an average

Humdrum….tediously fanciful….impenetrable”), and once hugely popular American mystery

writers Mary Roberts Rinehart (“crime stories which have the air of being

written specifically for maiden aunts”) and Mignon Eberhart, who barely rates a

sniffy mention. Repeatedly Symons

stresses his belief that the presence of a series sleuth was a ball-and-chain

around the narratives of Allingham and Marsh, stunting the artistic development

of their crime writing.

How

refreshing it is for me, as a lover of vintage detective fiction, to go back to

some of Symons’ earliest crime fiction reviews from the 1940s and 1950s—what

might be termed his pre-dogma days--and find him singing gustily a rather more

enthusiastic tune in regard to some of these same detective writers, as well as

others who were entirely omitted from the pages of Bloody Murder. It seems that

Julian Symons--like Raymond Chandler, another famous critic of Golden Age

detective fiction (see his essay “The Simple Art of Murder”)--was of a mind rather

more divided on the matter than he willingly acknowledged.

*******

One

of the biggest shocks, from one of Julian Symons’ “Life, People--And Books”

columns (1947) in the Manchester Evening

News, concerns Dorothy L. Sayers and the ardent devotion which Symons

professes to have for her criminal handiwork.

“A few weeks ago, Miss Dorothy Sayers, when asked if she was working on

a new detective story, replied that she was not,” Symons, then just

thirty-five, reported. “She added that

she did not even read new detective stories nowadays, because our present-day

mysteries were so markedly inferior to those of a few years ago. In common with many other readers I regard

Miss Sayers’ defection with dismay. I

hope she is really deceiving us, and is quietly hatching out a new story with a

brand-new detective.”

Were

Symons’ tears real human ones, or those of a crocodile? Perhaps his expressed hope that Sayers write

a new story with a brand-new detective really amounted to a wish that she would

rid the world of Lord Peter Wimsey. Yet

Symons claimed to regard her defection from detection with dismay. Symons even agreed with Sayers than detective

fiction in 1947 was worse than that from a decade earlier, although he praised

Christie, Carr and, more surprisingly, Ngaio Marsh, “who gives us every year a

piece of social satire with a mystery neatly embedded in it.” No complaints from Symons here about the “long

and tedious post-murder examinations of suspects” in Marsh’s mysteries, as

there would be in Bloody Murder.

In

a 1949 column Symons laments the loss of the “superman detective,” observing:

“The detective as a heroic or remarkable figure has almost vanished from the

detective story--and a certain liveliness has gone with him.” Fortunately for lovers of Super Sleuths there

was “Mrs. Agatha Christie,” who “may fairly be called the queen of detective

story writers now that Miss Dorothy Sayers has abdicated the throne; and it may

be fitting that, like Miss Sayers, she should have created one of the few

memorable modern detectives—the little Belgian Hercule Poirot….It is very

noticeable that the best of Miss Christie’s stories are those in which Poirot

appears.” So did Symons actually like

Lord Peter Wimsey at this time, then?

And if the presence of series detectives marred the work of Allingham

and Marsh, why did it not do so with Christie?

It

seems that back in the late Forties, Symons really liked those puzzles and he

was forthright in declaring his admiration for them, even at the expense of the

old Victorian masters of mystery whom he would later celebrate in Bloody Murder. “There are few more ingenious detective

writers than Ellery Queen and Carter Dickson,” Symons admiringly observed in

1949, sounding like a true modern miracle problem fanboy with a blog. “It is no exaggeration to say that in the way

they set and explain their puzzles these writers can knock Wilkie Collins and

Conan Doyle (or any other old-fashioned detective writer) into a cocked hat.”

By

1955, Symons, still conducting his column for the Manchester Evening News, admitted, in a review of Ngaio Marsh’s

latest mystery Scales of Justice, that he asked for “something more from the

modern detective story than a puzzle.”

Yet it seems that, at that time anyway, Marsh amply gratified Symons’

need:

The classical formula for the detective

story is well known. Introduce your

suspects in some rural scene. Let them

include the local vicar, doctor and solicitor.

Kill off the most unpleasant of them, and then proceed to long, long

interrogations by the police and amateur detectives….Ngaio Marsh uses this old

formula brilliantly….There are interrogations galore, conducted by that

gentlemanly professional Chief Detective-Inspector Roderick Alleyn. How is it that Miss Marsh managed to make all

this so wonderfully entertaining?

The

prime reason is that like all good modern crime writers she is also a lively

novelist. There is something individual

about her characters.

The

interrogation of suspects, as she manages it, reveals a genuine clash of

wits….Yet—and this is a rare thing—she can provide the puzzle, too. The solution…is highly ingenious. This is one of Miss Marsh’s two or three best

books. It is assured of a place on the

top shelf of crime fiction.

By

the time of Bloody Murder, however,

this “top shelf” Marsh had been, it seems, carelessly shelved. Yet in 1955 Inspector Alleyn and his endless

inquisitions had not served as an obstacle to Symons’ reading enjoyment--indeed,

far from it. What seems to have changed

is something in Symons himself. A

quarter of a century later, Symons selected, to represent Ngaio Marsh for the

1980 Collins Crime Club Jubilee Reprint series which he edited, not Scales of Justice but Spinsters in Jeopardy, an improbable

thriller that no one else I know of has ever praised as one of Marsh’s best

books. Citing “the problems facing the

writer [like Marsh and, presumably, himself] who wants to create characters,

yet knows the need to present and organize a puzzle,” Symons declared that happily

“Marsh has sometimes escaped from these problems by writing another kind of

book, the simple, pure, enjoyable thriller in which the puzzle is a secondary

element. Spinsters in Jeopardy is such a story.”

In

the same column in which he reviewed Marsh’s Scales of Justice, Symons assessed the detective novel Watson’s Choice by Gladys Mitchell. You remember Gladys Mitchell: the author

dismissed as “tediously fanciful” in Bloody

Murder. Back in 1955 Symons gratefully

deemed the author “an old reliable if ever there was one” and her latest book,

based on an “ingenious idea,” “well worked out” with “several good touches” (though

“rather lacking in liveliness”).

Admittedly this is a mixed review (Symons does so value “liveliness” in

murder fiction), but it is far from the curt dismissal which Mitchell receives

in Bloody Murder, where Symons acted

as if he could barely recall the poor woman.

At

least Gladys Mitchell merited a paragraph’s worth of notice in Bloody Murder. Other authors whom Symons once professed actually

to enjoy receive only the slightest of passing, patronizing nods in his 1972

survey. Take Elizabeth Daly, for

example. In Bloody Murder she is written off simply as one of the “Golden Age

writers whose work was once highly popular.”

However, in 1954 Symons reviewed her final detective novel, The Book of the Crime, in the Manchester Evening News, declaiming: “a

typical example of her craft, and very enjoyable it is too.” What was Daly’s craft, precisely? “[R]ather cozily horrific stories with a

strong feminine appeal.” Apparently this

appeal had become lost on Symons by 1972.

Then

there is the strange case of Mary Fitt, who in the Forties and Fifties had at

least three mystery books highly praised by Symons in the Manchester Evening News: the early Forties novels Death and Mary Dazill and Requiem for Robert, reprinted as Penguin

paperbacks (and soon to be reprinted in the present day by Moonstone Press with

introductions by me), and the short story collection The Man Who Shot Birds. The

novels Symons lauded lavishly as crime novels of character and atmosphere, although

he does not use the term explicitly. The

short story collection he raved as a model puzzler: “The detective short story

is a most difficult form—much more difficult than the full-length novel as

anyone who has tried to write both [like Symons] will know—and Miss Fitt

handles it very skillfully….the mysteries themselves are highly ingenious, with

false clues laid and misleading suggestions made most cunningly in limited

space.” By 1972, however, Symons

seemingly had forgotten that the talented Miss Fitt had ever existed, obviously

much preferring to write rapturously about the talented Mr. Ripley.

So

far I have detailed only women writers whom Symons left by the wayside or seriously

downgraded. One male writer who suffered

the same treatment, however, was versatile mainstream author Rupert Croft-Cooke,

who under his pseudonym Leo Bruce was during the Fifties and Sixties one of the

finest exponents of the classic detective story, which Symons insisted in Bloody Murder was rapidly wasting. In 1948 Penguin reprinted Bruce’s classic

debut detective novel Case for Three

Detectives, which simultaneously was an ingenious locked room puzzler and

an affectionate parody of Great Detectives Peter Wimsey, Hercule Poirot and

Father Brown. Symons’ praise for this

superb detective tale, which may have influenced his own poor attempt at

satirizing Philo Vance in The Immaterial

Murder Case, was high indeed:

I read “Case for Three Detectives” more

than ten years ago and thought highly of it then. I have refreshed my memory and can confirm

that this is one of the most slyly amusing tales of detection that has yet been

written. Lord Simon Plimsoll, Monsieur

Amer Picon and Monsignor Smith are three amateur detectives who bear a wicked

resemblance to the famous creations of Dorothy Sayers, Agatha Christie and the

late G. K. Chesterton.

Their

investigation of the mysterious death of Mary Thurston and the account of the

ingenious theories which are destroyed by solid, stolid sergeant Beef is very

good fun.

Yet

not a whisper of Bruce is heard in Bloody

Murder! Et tu, Brucey?

*******

Why

all these later revisions and omissions?

Was Symons simply a remarkably insincere reviewer in those Manchester Evening News pieces? Certainly there are always imperatives for

reviewers to give good notices to the books they review. Such notices make publishers happy, not to mention

readers, who are ever on the hunt for new books to read and do not like just to

be told how dreadful everything is. And

making both publishers and readers happy makes the reviewers’ employers happy

too, which is no small consideration. All

too often one has, after all, to sing for one’s supper.

Additionally,

most reviewers naturally dislike offending others. My previous blog post here at The Passing

Tramp, which criticized Julian Symons’ own first essay in crime fiction, that

weak little number The Immaterial Murder

Case (1945), provoked an internet friend of mine of over a decade’s

standing--a former blogger of fine distinction and discriminating taste who is also

something of a Symons fan, you might say--to accuse me, in rather off-color language, of wanting to “make Julian Symons

my bitch,” which took me aback. (I

assure you I have no desire to make anyone

“my bitch.”) In Symons’ case, he himself

was inducted into the Detection Club in 1950, meaning that he socialized with

some of the very writers he was reviewing above, like Christie, Fitt and

Mitchell. (Marsh, a native of New

Zealand, did not join the Detection Club until 1974.) Yet throughout his life Symons seems to me

to have been a man remarkably forthcoming, if not to say overbearing, with his

opinions and not especially concerned about hurting the tender feelings of

either authors or their fans.

In

the Sixties an incensed Margery Allingham took Symons’ mixed reviews of her novels

in the Sunday Times so personally that

she wanted to have him bounced from the Crime Writers Association. Across the pond, in the New York Times in 1977, not long after the death of esteemed

American mystery writer Rex Stout, creator of Great Detective Nero Wolfe,

Symons in a review of the recently published biography of the author boldly waved

a virtual red cape in front of the faces of Stout’s many fans, writing:

At the risk of outraging an accepted

American myth, it must be said that [Stout biographer Joseph] McAleer absurdly

inflates the [Nero Wolfe] stories’ merit….Stout was simply not in the same

stylistic league with Hammett, Chandler or Ross Macdonald. His prose is energetic and efficient, nothing

more. His plots lack the metronomic

precision of Ellery Queen’s….[The memorable Wolfe] operates in the context of books

that are consistently entertaining, but for the most part just as consistently

forgettable.

Letters of protest poured in from the late Stout’s offended American mythmakers, who angrily questioned whether any of this really must have been

said by Symons. Methodically Symons responded,

complaining at one point that one of the letter writers had been “gratuitously insulting”

to him.

Personally I do not doubt that in his

book reviews Symons was expressing his genuine beliefs at the time. What produced the change in them, then? I think over time Symons’ views hardened into

inflexible dogma, producing in Bloody Murder

a crusading book in which he was determined, finally, to put puzzle-oriented

detective fiction in its lesser literary (or non-literary) place for once and

all as the sort of freak it was, a changeling which had mischievously replaced

the crime novel in its cradle back in the Twenties and Thirties and continued ever

since to receive nostalgic genuflection.

Additionally I think Symons genuinely had gotten bored with detective

fiction, having had to read so many pedestrian examples of it in his capacity

as the Sunday Times mystery reviewer

for a decade. (Dorothy L. Sayers had

only been able to stick it out in that job for a couple of years). In Bloody

Murder Symons recalls that “I gave up [reviewing mystery fiction at the Sunday Times] chiefly because I knew I

was becoming stale, so that my reaction on seeing a parcel of new books was not

the appropriate slight quickening of the pulse marking the hope of a

masterpiece. I opened it rather with the

expectation that the contents would fulfill my belief that almost all crime

writers publish too much.”

Ironically

Bloody Murder--that lauded, landmark

study of mystery, detective and crime fiction--was written by a man nearing his

seventh decade who had lost his youthful enthusiasm for detective fiction and become

to a great degree jaded with the very genre to which he had devoted his

book. While he was able to summon up

something of his juvenile passion for Christie, Queen, Carr and even, in a true

testament to the power of nostalgia, Philo Vance—it appears to me that what he

now wanted desperately was for murder fiction to mean something, for tales of violent death to say something

meaningful to him about life. “Bloody Murder…makes discriminations

between thoroughbreds and hacks,” the ailing Symons declared in a cri de cœur near the end of the ‘92

edition, published not long before his death.

“It was part of my hope and intention that the book would, through such

discriminations, raise the status of the best crime stories so that they would

be considered seriously as imaginative fictions.” The books by “serious” crime writers like

Patricia Highsmith, Dashiell Hammett, Eric Ambler, he still found rewarding

reading, but so many other makers of mystery seem largely to have lost their

luster for him. Perhaps Bloody Murder should have been titled Bloody Bored.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.JPG)