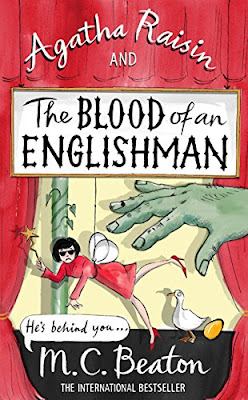

At the time of its publication, The Blood of an Englishman (2014) was advertised as something of an "event" in crime writer MC Beaton's long-running Agatha Raisin mystery series, as it was the author's 25th book in the series. Only five more Raisins from the author's hand (ostensibly) followed it before her death at age 83 on the last day of 2019. The series has since continued under the hand of R. W. Green (a man, Rod Green), who has been described as a longtime friend of Beaton.

Personally, I suspect Mr. Green, not of having done it with the revolver in the billiard room, but of having helped in the writing of the last of the Beatons ostensibly produced by his benefactor, Beating about the Bush, published the year of her death, because to me it doesn't read quite like Beaton herself and it is a huge improvement on her previous two Raisins, The Witch's Tree (2017) and The Dead Ringer (2018), which are, to be brutally frank, two of the worst mysteries I have ever read. Sadly, they are practically unreadable, like Agatha Christie's Postern of Fate (1973) without that novel's dotty, meandering charm. I haven't read the two Raisins which come between Blood and Tree (Dishing the Dirt and Pushing up Daisies), but Blood comes off like a work of sheer genius compared to Tree and Ringer, though in fact Blood is very much adulterated in my view.

.jpg)

When The Blood of an Englishman was published in 2014, the Agatha Raisin series had been in sharp decline for some time, since approximately 2008. The year before that, in the rather charming (if you like the series) Kissing Christmas Goodbye (2007), the eighteenth Raisin novel, Beaton had introduced Toni Gilmour, a young, beautiful sidekick for Agatha Raisin, who had graduated from amateur village snoop to licensed private detective in the fifteenth Raisin novel, Agatha Raisin and the Deadly Dance (2004). The first few PI Raisin books aren't bad, in my opinion, but the wheels start to come off the dead cart with A Spoonful of Poison (2008). I don't blame Toni for this but rather structural changes that Beaton made in the books at the time.

The books start to rely much more on barking mad murderers, the body counts rise to absurd levels, the plots become disjointed and chaotic, Agatha is put in more perils of her life than Pauline and there's this weird thing where the murderers get revealed early and then the last chunk of the novel concerns the murderer plotting, futilely of course, to kill Agatha, after which there is an epilogue introducing the setup in the next, apparently already written book.

Beaton's cast of longtime supporting characters continue to make appearances, but these appearances feel ever more rote. The charm of life in the Cotswolds village of Carsley, so well-depicted in the debut novel in the series Agatha Raisin and the Quiche of Death (1992) and others which followed it, is lost.

Indeed, after Kissing Christmas Goodbye, the lone bright spot in the series for me has been Something Borrowed, Someone Dead (2013), which immediately preceded The Blood of an Englishman. Although it shares the same narrative structure of the later Raisins, Borrowed benefits from a better plot and choice of murderer. But let's look in more detail at Blood below, shall we? Following this list of the Raisin novels, provided so that you can better follow what I have been saying, along with my ratings of them. (Imagine they are raisins rather than stars.)

Agatha Raisin and the Quiche of Death 1992 ****

Agatha Raisin [hereafter AR] and the Vicious Vet 1993 ***

AR and the Potted Gardener 1994 ***

AR and the Walkers of Dembley 1995 ***

AR and the Murderous Marriage 1996 ***

AR and the Terrible Tourist 1997 ***

AR and the Wellspring of Death 1998 ***

AR and the Wizard of Evesham 1999 ***

AR and the Witch of Wyckhadden 1999 **

AR and the Fairies of Fryfam 2000 ****

AR and the Love from Hell 2001 ****

AR and the Day the Floods Came 2002 ***

AR and the Curious Curate 2003 ****

AR and the Haunted House 2003 ***

AR and the Deadly Dance 2004 ****

AR and the Perfect Paragon 2005 ***

Love, Lies and Liquor 2006 ***

Kissing Christmas Goodbye 2007 ***

A Spoonful of Poison 2008 **

There Goes the Bride 2009 *

The Busy Body 2010 -

As the Pig Turns 2011 *

Hiss and Hers 2012 *

Something Borrowed, Someone Dead 2013 ***

The Blood of an Englishman 2014 **

Dishing the Dirt 2015 -

Pushing up Daisies 2016 -

The Witch's Tree 2017 NONE

The Dead Ringer 2018 NONE

Beating about the Bush 2019 (with R. W. Green?) -

In Blood, Agatha attends a pantomime of Babes in the Wood (mashed up with Mother Goose, Jack and the Beanstalk and other tales) in the nearby village of Winter Parva with her saintly friend and moral mentor (to the extent this is possible with Agatha), Mrs. Bloxley, the wife of the rather less patient and forbearing vicar of Carsley, improbably named (as Agatha herself thinks) Alf. When the man playing the ogre, bullying baker Bert Simple, is eviscerated by a metal spike when exiting the stage via a trapdoor drop, Agatha is hired by the play producer, Gareth Craven, to find the depraved culprit. Agatha is not notably successful in this endeavor (to be fair, neither are the police), for it's not long before, after a performance of The Mikado, another actor is decapitated with the (real) sword of the Lord High Executioner.

Why do they call these books cozies again? These are very unpleasant killings (and there's another one, which I can't divulge, which is even worse). Even Mrs. Bloxley doesn't mince words (well, not much) in reference to the neutering of Bert Simple, commenting that the villain "plotted not only to kill him but to destroy his manhood in the process." Nice to know that cozies can encompass emasculation and decapitation and--well, I can't mention the other thing. With some tonal shifts this book could have been written by Jo Nesbo!

Blood has a lot of the flaws characteristic to the late Raisins, including the sidelining of a great many of the series' longtime supporting cast members and an overemphasis on Agatha's dysfunctional love life, or more accurately lust life. Anyone reading many of these books must surely start to wonder how much MC Beaton actually liked women. So many of them, including Agatha herself, are messes, hot and cold.

Aside from the fact that Agatha Raisin, in the depiction of whom the author said she drew upon herself, repeatedly denounces feminism for ruining romantic relationships between the sexes, there's the fact that Agatha is such a basket case in her relationships with men. In Book 5 her marriage ceremony to her handsome neighbor James Lacey, a Jane Austen hero with the stodginess and emotional repression dialed up to 99, is interrupted when her long lost (and conveniently assumed dead) husband Jimmy shows up, then in Book 11, when Agatha and James finally do marry, the union is a train wreck that lasts out only this one novel.

There are other men whom Agatha gets interested in and even sleeps with over the course of the series, including charming if rakish aristocrat Sir Charles Fraith, but usually they turn out to be utter scoundrels. Still over and over Agatha falls head over high heels (she hates flats) in love with any handsome man she meets. No wonder in Blood, her friend with occasional benefits Sir Charles thinks: "It would be hopeless being married to her....He would never be able to trust her. Agatha would always be one woman looking for an obsession."

.jpg) |

"If I were only fifty years younger!"

MC Beaton tweeted this sentiment

in 2017 concerning this pic of herself

and scrumptious actor Matt McCooey,

who plays cop kindhearted Bill Wong,

Agatha's first friend by her own admission,

in the Agatha Raisin television series |

When I started this series I had a notion that Agatha, she of the breakfasts of back coffee and cigarettes and the perpetual gins and tonics, was some sort of tough feminist icon, but she's really nothing of the sort, even though she's a highly successful, frequently ribald, retired PR executive. Her neuroses. mostly over men and her appearance but also concerning her lower class social origins, pull her down constantly. She does have her genuine feminist, girl power moments, like when she storms the woman-averse pub in Fairies of Fryfam, one of the best books in the series, but all is canceled out with her desperate man chasing and pathetic obsession with her looks.

I recall there was a woman character in a satirical meta episode of the American sitcom Newhart, the horny middle-aged single woman neighbor, who was introduced as "Man-crazy Smitty." Well, that's Agatha to a "T." Despite all her professional successes she just can't get along without a man in her life. She even goes about with her ambiguously gay "toy boy" pal from the City, Roy Silver, when no other man is available, pale and weedy and effeminate as Roy is invariably described.

In Blood Agatha gets smitten with handsome men four (!) times, though in the one case the passion is somewhat lukewarm because the man has a weak chin, that bane of Golden Age crime fiction, at least as far as men were concerned. (Conversely with women strong chins were problems.)

|

| just your typical gay shindig |

In another case, the man sadly turns out to be gay, a fact to which Agatha tumbles when he invites her to a party he has thrown where the parking attendant is wearing a "hat, black leather thong and nothing else." I'm guessing Beaton got her notion of this little shindig from watching Elton John's forty year old "I'm Still Standing" video.

There at least is some relationship to the plot in all but one of these cases, but at this point in the series I just find Agatha's obtuseness in regard to men and her low self-esteem not sympathetic but simply exasperating. She's like the Bill Murray character in the Nineties romantic comedy Groundhog Day, had he never learned anything whatsoever from repeating the same day over and over again.

Was the author herself really anything like this? If so I think I can see how she ended up handing off authorship of the series (and the Hamish Macbeth one too)not to anoither woman writer but to a ruggedly handsome male friend--no toy boy he--named Rod. She strikes me as rather a man's woman.

|

| Rod Green |

The plot in Blood isn't bad, actually. The climax, which occurs when a fifth of the book yet remains, is actually intriguing, though it's stolen from another, rather famous crime source. (Let's call it an homage, since the source is actually mentioned in the book.)

Unfortunately, everything then is dragged out as the murderer pursues Agatha, even abducting her a second time and trying to kill her by throwing her in a river while confined in a barrel. (It really is very Perils of Pauline.) By my count this is only a 60,000 word novel, but at least 10,000 words could have been profitably cut from it.

Agatha's great days in book form were the fifteen years between 1992 and 2007, when you could still hold out hope that Agatha might come to her senses about men. Really, she and Charles, who latterly carried the series on his nattily-clad, aristocratic shoulders (Mrs. Bloxby and Roy help), should have married after Love, Lies and Liquor, by which time any fan of the series should have wanted to see James Lacey get his richly deserved comeuppance.

The popular ongoing television adaptation of the Agatha Raisin novels makes the characters more likeable generally, including Roy Silver, James Lacey and, most crucially, Agatha herself. The TV series is genuinely warm and cozy, Sex and the City-ish gay sex jokes notwithstanding. That the Agatha Raisin novels are "cozy" is something I have to question. The tea has a lot of gin in it, and the saucer is littered with stubbed-out cigarettes.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)