Mrs. Carter Giles, for decades the dowager of Bridgehaven, decided that her contribution to the war effort would be opening her house to the war workers who were overcrowding her little city. She expected to be able to pick her lodgers with the discrimination for which she herself had always been noted. But Fate and the lodgers decreed otherwise, and a few hours after the invasion of her motley crew, Mrs. Giles found a body under the bushes next to the house....

--from the front jacket flap of

The Case of The Dowager's Etchings (

Doubleday Doran, 1944)

River Rest was a JUNGLE--And he would be king of this jungle. He moved down the carpeted hall, his animal senses alert and quivering....Only an old woman stood between him and his dream of wealth....Without realizing it, Carrie Giles had become a stranger in her own home. Four roomers had moved in. Three were cold-eyed men. The fourth was a predatory female whose every word and gesture was a wanton invitation. All four were interested in Carrie's etchings. But she never knew why--until a silent killer walked into her room!--from the back cover of

Never Walk Alone (formerly

The Case of the Dowager's Etchings) (

Popular Library, 1951)

|

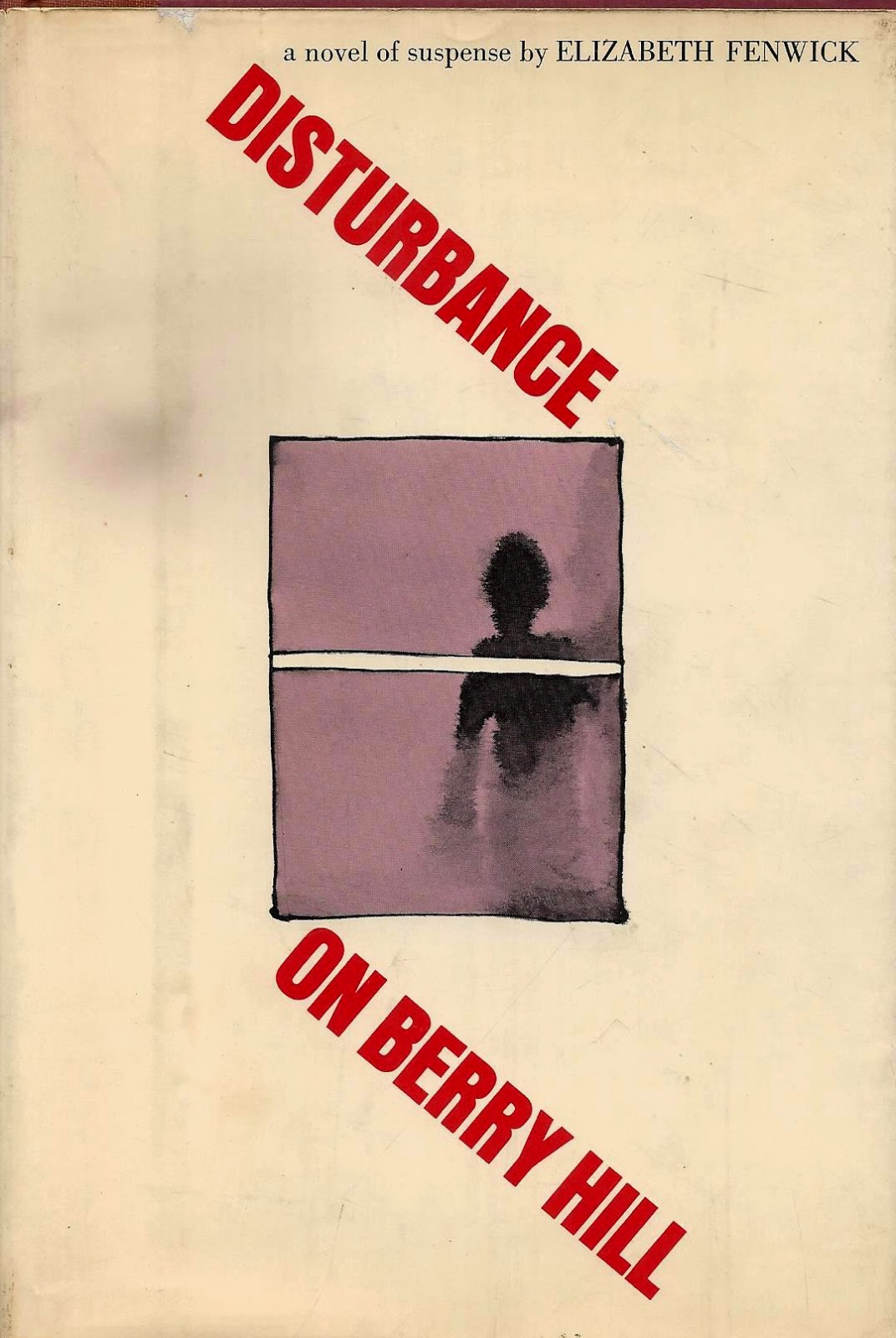

| Going stag: the hardcover edition |

Surely nothing in crime fiction illustrates the calculatedly salacious marketing of fiction in the early years of the paperback revolution than the startling transformation of

Rufus King's

The Case of the Dowager's Etchings (a 1944 hardcover) to

Never Walk Alone (a 1951 paperback).

This remarkable publishing alchemy is a process that academia now metaphorically designates "pulping," i.e., making books more available to readers as cheap paperbacks with vivid, sexualized covers--often adapted by artists from original pulps art--guaranteed to catch the eye, titillating many, while outraging others (in the 1950s Congressional pressure would encourage publishers to tone down the covers).

In 1944,

The Case of the Dowager's Etchings was published by that great warhorse of American crime fiction publishing, Doubleday Doran's Crime Club. By this time the Crime Club had a visual categorization system with an array of symbols meant to immediately signify to Crime Club members and potential buyers what kind of mystery they were getting with each title.

The Case of the Dowager's Etchings was denoted with a clutching hand, signifying "

character and atmosphere."

|

| Rufus King in the 1930s |

This is a fair classification. Although in the 1930s Rufus King, like

John Dickson Carr, opted in his mysteries for fleeter, more thrilling fictional narratives than those of the so-called "Humdrum" school of

Freeman Wills Crofts,

John Street and others, he nevertheless fashioned these narratives in the form of classical detective fiction. By the 1940s, however, King was moving away from the traditional detective fiction form to something more on the order of the suspense thriller. Perhaps the best known of this group of King crime novels is

Museum Piece No. 13, a modern Bluebeard fable that was filmed, with significant differences from the novel, as

The Secret Beyond the Door (1947) (see my review of the novel

here).

The Case of the Dowager's Etchings is a fine example of suspense fiction, but where

Museum Piece No. 13 is predominantly Gothic and gloomy,

Etchings conforms much more to the novel of manners style most associated today with the British Crime Queens

Dorothy L. Sayers,

Margery Allingham and

Ngaio Marsh, with some good character studies, witty writing and minute social observation.

The protagonist of

Etchings, the blue-blooded Carrie Giles (

Mrs. Carter Giles), is a skillfully-delineated character, one of a long line of memorable wealthy matrons in Rufus King's fiction. King, who grew up in New York City in privileged circumstances--prep school and Yale; summers in Rouses Point, a town at the northern tip of Lake Champlain just below Canada; winters in Florida) no doubt knew such people well (I suspect he drew partly on his own mother).

Although it is unquestionably a slighter novel,

Etchings reminds me to some degree of

Elisabeth Sanxay Holding's brilliant crime novel

The Blank Wall, which it preceded by three years. Holding's novel, also set during the Second World war, offers a fascinating look at social changes wrought by the conflict, particularly in the roles of women, including, in the case of the protagonist of that novel, wealthy, sheltered white matrons.

King skillfully navigates this same process of personal growth with Carrie Giles, who feels, in an increasingly democratic age, obsolete and resented by the local

hoi polloi, some of whom make their feelings vocal when they see her being driven about town, to their disgust, in a Victorian carriage, pulled by a "

roached black mare" (Mrs. Giles brought out the carriage again because of wartime gasoline rationing).

|

| Rooms to let: all just as Papa left it |

Her dashing grandson is a war hero, but Mrs. Giles wants to do more personally for the patriotic cause; so she decides to open her mansion to take in a quartet of war factory workers, having learned that housing for these people is inadequate and overcrowded. Regrettably for Mrs. Giles, trouble soon flows from this noble resolution. As the hardcover edition explains, not long after she takes in her new boarders, she finds a dead body in the bushes. Soon Mrs. Giles is tangling with mysterious forces that seem to have criminal designs centering on her house. Who can she trust? And will the killer feel compelled to kill again?

Mrs. Giles does some investigating in her own right and King offers readers one splendid clue, so there is genuine detective interest in

Etchings, but I think readers may enjoy the novel most, like I did, for its "manners."

One of my favorite aspects of the novel is how King has Mrs. Giles, a woman in her seventies, constantly reflecting on the things her Papa did or said. It seems like practically everything in the mansion, River Rest, was purchased by Papa or chosen by Papa. It's a wonderful portrait of a masterful Victorian father, sublimely confident even when utterly mistaken and though long dead still a great influence on his daughter (however there are signs his grip finally may be slackening).

In its blurb the hardcover edition of

Etchings doesn't mention, oddly, the Victorian-era etching, a pastoral scene with stag done by Mrs. Giles, that figures significantly in the plot, though it is depicted in the somewhat stodgy front cover illustration. On the whole, however, the plot description details the novel's doings dutifully, if a bit dully.

|

| Cinematic: ready for their closeups |

With the 1951 Popular Library paperback edition,

The Dowager's Etchings got a major makeover. On the cover we have quite a dramatic moment, courtesy of

Rudolph Belarski (one of his best pieces of work I think). A character in the book explicitly is compared to

Humphrey Bogart, and certainly that man on the cover bears resemblance to the actor.

In the novel there also is a sexy, brassy woman factory worker (

Rosie the Ravisher one might say, or, as the back cover blurb rather overheatedly puts it, "

the predatory female whose every word and gesture was a wanton invitation"). I assume this is meant to be the woman on the cover who resembles

Rita Hayworth (it's certainly not Mrs. Giles).

The problem is this scene never quite occurs in the book! Nor does the new title seem very particular to the novel. Perhaps it's meant to reflect how Mrs. Giles has to rely, amid great danger, on her own devices in the crisis she faces, with her beloved grandson frequently sidelined? Was the publisher drawing on "

You'll Never Walk Alone," the

Rodgers and Hammerstein hit from

Carousel (1945)? (The song is vastly more familiar to my British readers, I suspect, in this

version by

Gerry and the Pacemakers.)

Don't let any misleading cover art or blurbs spoil your enjoyment of the actual text of the book.

The Case of the Dowager's Etchings is another great novel from an American Golden Age Crime King, whatever one puts on its covers.

Other Rufus King novels reviewed at The Passing Tramp:

Maneaters: Murder by Latitude (1930)

Tempests: Murder on the Yacht (1932)

Reefs: The Lesser Antilles Case (1934)

Good news too for fans: All the Rufus king novels are being reprinted, by Wildside Press. I wish I could say I has something to do with it (I had been trying for years), but at least it's finally happening.

.jpg)