--Death Sails the Nile, by Frances Burks

McKinley

Earlier this year Coachwhip reprinted Death Sails the Nile by F. Burks Mckinley, the semi pseudonym of native Tennessee author Frances Burks. It was published four years before Agatha Christie's rather more famous Nile slay sojourn, but in my opinion it merits reading today, being a nifty mystery tale. Additionally the author was an interesting person from a fascinating, if sometimes tragic, family background. That part of the story will appear in a second post. For now, here is some more about the book.--TPT

During her leisurely 1929 Mediterranean honeymoon with her new husband, Vanderbilt history professor Silas Bent McKinley, Vanderbilt graduate Frances Burks with Silas visited the Egyptian city of Luxor, where, in addition to seeing some of the greatest antiquities known to mankind, the couple encountered that “Lord of Reptiles” and veritable “King of Wizards,” Sheikh Moussa (or Musa, which is Arabic for Moses), who was then the most renowned of Egypt’s fabled snake charmers. Four years later, when writing her detective novel Death Sails the Nile, Frances placed Moussa/Musa, his name changed to “Nusa,” in the first chapter of the novel. There he is overheard by newspaperwoman Mona Case and her young shipboard pal Jimmie Bean, both of whom are passengers on the Nile River dahabeah (tour boat) Assuit, in the act of presenting an unknown person with a baneful gift of two deadly asps.

Is it a coincidence, then, when, on the very next day, another passenger on the boat, glamorous ash blonde Celia Lawton—“a magnet that attracted to its dynamic center every male eye within range, and every woman’s too, for that matter”—suddenly crumples and dies, while standing before an image of Anubis, dread Egyptian god of the afterlife, at the ancient Abu Simbel temple complex, the victim (like, legend tells us, Cleopatra before her) of a fatal bite from an asp? You surely already know the answer to this question, my dear blog readers!

Thus begins a reign of terror aboard Assuit that ultimately will claim three more lives before the ill-fated dahabeah reaches the protection afforded by modern civilization’s gendarmerie. Besides Mona and Jimmie and the late Celia Lawton, the boat’s other Europeans and Americans (this being a Golden age mystery, the Arab crew is considered, to borrow John Dickson Carr’s apt phrase, “below suspicion”) are the rotund medico and captain, Dr. Bradshaw, and the remaining surviving passengers.

These are:

Professor Cross, an acerbic archaeologist

Jack Spencer, a devilishly charming man-of-the-world

Ella Singlefoot, Mona’s primly outspoken spinster aunt

Tom Amory, a hulking engineer said to have been, up until her ghastly untimely death, Celia’s fiancée

Colonel Worthington, late of the British Army, and his wife, Sophie, formerly a chorus girl in the Ziegfeld Follies

and last but not--well, yes, actually--least, Celia’s plain Jane maid, Jane Davet.

Who among them next will be dastardly done to death before intrepid Mona Case discovers both a motive and a murderer?

Readers who peruse my forthcoming biographical post on Frances Burks may perceive some similarity between Mona Case and the author. Not only is 25-year-old Mona Case the same age as Frances Burks when she was writing the novel, she bears a physical resemblance to her as well and seems in some ways a fantasy projection: a person who chose the life of an independent career woman, which the author herself forswore when she married Silas Bent McKinley. After her divorce from Silas, Frances talked of becoming a journalist. She tellingly describes Mona as follows:

Twenty-five years of active and strenuous American life had given Mona Case unusual poise and an air of assurance. In four years after leaving college she had established a definite place for herself in the newspaper world….She was of medium height, slender, with a mass of short auburn curls topping a well-shaped head. She combined in her person the qualities of physical strength and vivacious charm. Her blue eyes, set far apart, gave an impression of candor, yet it was the square clean cut chin, which while preventing her from being beautiful, stamped her character as forceful.

Possibly Mona’s aunt, Ella

Singlefoot--arguably the most memorable character in Death Sails the Nile with her caustic observations on the other

female passengers on board the Assuit

(“Long years of spinsterhood in a small southern town had made her critical of

women surrounded by male admirers. She

had seized upon each morsel of gossip concerning Celia Lawton…and had devoured

it avidly.”)--was inspired by Frances’ only real life aunt, Ida Frances Burks, the

wife of beloved small town doctor William Martin Breeding, whom Frances would

have known when she resided in Livingston, Tennessee.

Certainly Jimmie Bean, afflicted on the cruise “with the boredom of one

just out of college,” recalls Frances’ brother, James Willis Burks III, who

seems to have been something of a gay blade in the Thirties, attracted to women

rather like the former Follies dancer Sophie Worth.

|

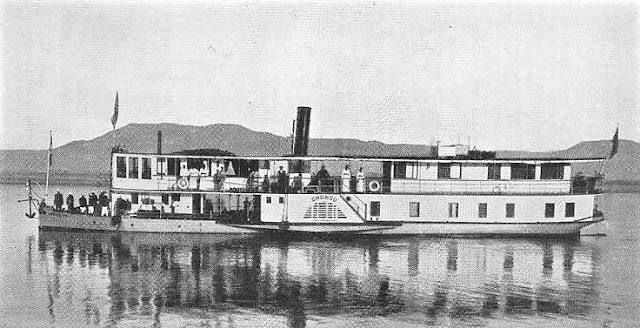

| approaching Abu Simbel temple complex |

As for the question of whether Agatha Christie might have been influenced by Frances Burks’ Nile murder mystery, who really knows? The novel does not appear to have been published in England, but certainly its second murder—the stabbing of the blackmailing crewman Abdu, who is found clutching a fragment of a banknote in his hand—recalls the second murder in Death in the Nile, a novel which enjoys, if that is the right word, a similarly high body count. Additionally, the first murder victim, the wealthy, beautiful and proud American Celia Lawton bears a certain resemblance to Christie’s murdered American heiress, Linnet Doyle.

Although no Death on the Nile, to be sure, Death Sails the Nile in the estimation of contemporary critics was a fine detective novel, despite some technical blemishes characteristic of a novice in the field. It was lauded in the New York press by crime writer Norman Klein in the New York Evening Post (“Contains many an attack of gooseflesh—suspense very well maintained”), Isaac Anderson in the New York Times Book Review (“An exciting crime puzzle”), Will Cuppy in the New York Herald Tribune (“Has real excitement, not to mention an interesting background, shuddery until the final revelation”). The American heartland chimed in with praise as well, the Minneapolis Star, for example, assuring readers, “You’ll find clues aplenty and a logical plot, but [as well] some queer turns that will surprise you….[The author] has indeed made an auspicious start.”[1]

With such reviews as these, Frances Burks seemingly had ample reason to launch Mona Case on a second amateur mystery investigation, yet soon after the publication of her book she seems effectively to have laid down her pen. Although Frances had hopefully dedicated Death Sails the Nile to her husband Silas, her character Ella Singlefoot’s rueful reflection on men and marriage—“So much was demanded of their wives, yet the men themselves were frequently indiscreet”—hints at the draining emotional storms that lay ahead of the couple. It is most regrettable that intense marital turmoil capsized Frances Burks’ nascent mystery writing career, but happily her sole detective novel, a worthy example of Golden Age art and artifice, now stands as a tribute, in its own modest way, to a woman of evident promise.

|

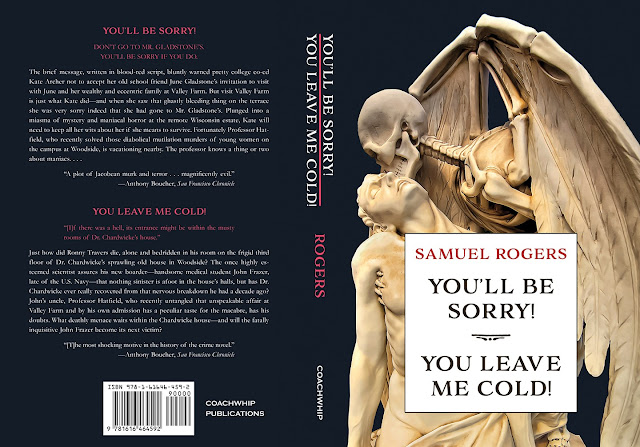

| not a miss--Cleopatra and the asp by Michelangelo (c. 1535) |

Even genre masters have occasional misses!