One of the great twentieth century public intellectuals, the historian and literary critic

Jacques Barzun, died yesterday, at the age of 104. You will find tributes to Professor Barzun's myriad accomplishments over his long life in the

Washington Post, the

New York Times, the

Telegraph, the

Independent and many other locations around the internet.

At

The Passing Tramp, of course, we focus on the mystery fiction genre. Professor Barzun's contribution to the study of this branch of literature was of great significance, though it does not get much attention in the newspaper obituaries.

|

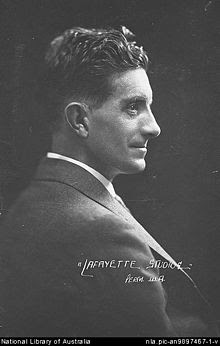

| Jacques Barzun (1907-2012) |

Much to my regret I never met or corresponded with Professor Barzun, but as a reader of mystery fiction (and more recently a historian of it) I have lived with Barzun's powerful presence in my mental life for over two decades, ever since I read his and his colleague Professor

Wendell Hertig Taylor's magisterial critique of crime fiction,

A Catalogue of Crime (ACOC).

Originally published in 1971, ACOC was revised by Barzun and Taylor and reprinted in 1989 (Professor Taylor died four years before the new edition appeared, at the age of eighty; incredibly, Professor Barzun would outlive his old friend by nearly thirty years).

The new edition of ACOC fell just short of 1000 pages, with entries on over 5000 works: novels, short story collections, mystery genre studies, true crime studies and Sherlockiana. Additionally both the revised edition and the original editions have characteristically incisive essays by Professor Barzun on the nature of mystery fiction.

|

| a magisterial, controversial, volume |

ACOC is best known for its defense of the true detective story--i.e., a story centered on true detection or ratiocination, or, as Barzun cogently put it, "

the rational linking of fact, motive and explanation."

Professor Barzun greatly admired detective fiction, but he argued that it was properly understood as belonging to that category of literature known as the

tale. As a tale, the proper aim of the detective story is entertaining the reader by "

exercising the imagination."

Any "

attempt to make a crime story 'a real novel' is headed for failure," Barzun pointedly pronounced in the 1989 edition of ACOC.

This position naturally put Professor Barzun at loggerheads with those who believed that the highest aim of mystery or crime writers should be to "

transcend the genre," as the phrase goes, and produce what essentially are "straight" novels, albeit with a crime element.

A year after ACOC originally appeared, the eminent English crime writer and critic

Julian Symons (1912-1994) published his seminal history of the mysterious genre,

Bloody Murder (originally titled

Mortal Consequences in the United States). Like ACOC,

Bloody Murder was an influential work over the 1970s and 1980s and into the 1990s (it had three editions, the last appearing twenty years ago, in 1992).

|

| a contrary opinion |

Julian Symons took the opposite view from Professor Barzun, arguing that the best crime genre fiction was precisely that which attempted to approach so-called "mainstream" novels, by emphasizing psychological character studies and searching examinations of society (it should be noted that Symons eventually declared that crime fiction by its inherent nature could never attain the highest level of great literature, a position that confounded and vexed many of Symons' admirers).

These two polar opinions dominated much of mystery fiction analysis for some time, with partisans of both men exchanging rhetorical fire (Symons had more supporters, but long odds and lack of reinforcements never daunted the intrepid Professor Barzun).

Only in the last twenty years has the explosion of academic crime fiction criticism largely turned the preferred subjects of conversation to other things, particularly the genre's approaches to the subjects of race, gender, class and sexuality (you see, just like the mainstream novel!).

Yet the concerns of Barzun and Symons remain alive today with mystery writers and readers.

Ian Rankin complains bitterly about "serious" crime novels not winning Bookers, while traditionalist detective fiction fans pine for that mystery in which the author might actually deign to dangle clues before readers.

I first came across reference to Jacques Barzun's writing on mystery fiction in 1989, when reading the English mystery writer

Robert Barnard's fine study of the genre fiction of

Agatha Christie,

A Talent to Deceive (like Barnard, Barzun held Christie's writing in great esteem).

When I started my graduate school studies in history in 1991, I sometimes used to spend time in between classes reading the massive second edition of ACOC in the reference library of

Louisiana State University in

Baton Rouge (other favorite references of mine at this time was

Bill Pronzini's and

Marcia Muller's

1001 Midnights and Pronzini's

Gun in Cheek). Although I had read

Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie and the other British Crime Queens and started my way through

John Dickson Carr's books (

Doug Greene's splendid biography of the locked room master would soon be out), I had had no clue previously that detective fiction was so rich and varied.

|

| Dedication in Masters of the "Humdrum" Mystery |

Reading ACOC started me off on the long, long trail of writing

Masters of the "Humdrum" Mystery: Cecil John Charles Street, Freeman Wills Crofts, Alfred Walter Stewart and the British Detective Novel, 1920-1961, which, as readers of this blog will know, was just published by McFarland this year.

It's inconceivable to me that this book ever would have happened had Professor Barzun not lived. Barzun greatly admired the work of Street (

John Rhode/Miles Burton), Crofts and Stewart (

J. J. Connington), particularly that of Street (there are entries on 93 of Street's novels in the second edition of ACOC, taking up over sixteen pages). I felt it only proper that I dedicate

Masters to Professor Barzun (along with Doug Greene and Bill Pronzini).

|

| John Street (1884-1964) |

Julian Symons somewhat derisively labeled these authors "Humdrums" (Street and Crofts, anyway; he was less clear about Connington). Barzun begged to differ. Major Cecil John Charles Street "

has been called dull," noted Barzun in the second edition of ACOC, "

most unjustly." Street, Barzun asserted, "

achieved excellence, again and again....Not only were his plots based on solid and original schemes, but at his best he made character and action fresh and engaging as well as functional."

To be sure, Professor Barzun's taste in mystery fiction tended to be austere. For example, Barzun disliked broad humor in detective fiction. John Dickson Carr,

Ellery Queen and other ingenious American masters of mystery he tended to find too outre for his taste, thus cutting himself off from natural supporters among fans of these more colorful practitioners of true detection. Additionally, Barzun generally favored classical mystery over more tough (hard-boiled) stuff.

Yet when Julian Symons asserted that he and and Barzun shared no common aesthetic ground, he went too far. Barzun lauded novels by authors whom Symons similarly highly praised--

Raymond Chandler, for example (Barzun rightly challenged the myth that Chandler was incapable of plotting coherently). Indeed, Professor Barzun even praised works by Julian Symons and included Symons'

The Narrowing Circle (1954) in his

One Hundred Classics of Crime. Where specific crime fiction titles are concerned, there is more common ground to be found between these two men than generally is realized.

|

| Jacques Barzun |

Jacques Barzun began writing about crime fiction as far back as the 1940s, when he was a young professor at

Columbia University. Up until yesterday, he was one of the few remaining living people who read

Sherlock Holmes stories in their first appearances in the

Strand.

Professor Barzun's views on detective fiction were controversial from the beginning. The prominent and beloved mystery critics

Anthony Boucher and

Howard Haycraft both took aesthetic issue with him in the forties. Haycraft refused to include a Barzun essay in his 1946 anthology

The Art of the Mystery Story, dismissively labeling Barzun, in a blunt letter to Boucher, "

a very dilly tante" (rather a clever pun, if unmerited).

Whether one agrees with Barzun's general view of mystery fiction or his opinions on specific authors, there is no denying his forceful and eloquent defense of the place of

detection in detective fiction. Among his many accomplishments in literary criticism, Professor Barzun made a persuasive case for the true art of detective fiction that entertains through stimulating the mind's ratiocincative capacity; that is no mean thing.

I salute your distinguished life and work, Jacques Barzun.