|

| cover by Barnard's English publisher in his later years, Allison & Busby |

Wednesday, September 21, 2022

Butcher's Dozen: Robert Barnard's Thirteen Best Mystery Novels

More of the Art of Agatha: Further Examples of (Mostly) Exquisite Christie Paperback Art

.jpg) |

| William Teason, 1968 Readers of the book will know how clever a cover this is |

Mid-century Agatha Christie hardcover art was often deadly dull indeed, with the publishers seemingly relying on Christie's name alone to sell books (not a bad call either, that).

However the paperback art for Christie's books was another case entirely. I have already done posts on some of the superb artwork for Pocket done by Tom Adams and the lesser known Mara McAfee.

Here are additional some examples of Christie paperback art:

Works by William Teason, who did Christie covers for Dell from the Fifties into the Seventies

Some of the more surrealistic Christie covers Tom Adams did for the English publisher Fontana in the Seventies and a couple more of his wonderful Pockets I have found

Some examples of Bantam and Pocket paperback editions I purchased as a kid back in the Seventies and the Eighties with appropriately, my own pocket money

Those later Pockets bring back tremendous nostalgia for me, of a time when reading mysteries was really exciting, in a way it never has been quite since: the thrill as a kid of desperately trying to determine just whodunit--and usually never coming close succeeding!

.jpg) |

| Some of the surrealistic images from Tom Adams' wild Fontana covers As weird as this Caribbean Mystery cover is, he did an even weirder one, with just the old Major's glass eye! |

.jpg) |

| Here Adams vividly depicts the murder scene in MMD and a pivotal moment in TMC. Clever! |

.jpg) |

| the back covers |

.jpg) |

| These later Pocket designs were rather minimalistic, but I always found the Ordeal cover from 1976 rather sinister. I remember trying to figure it out and being completely gulled. |

.jpg) |

| William Teason, 1970 and 1969 He loved the skull motif and a variety of weapons. |

.jpg) |

| presumed William Teason, the classic items composition design |

.jpg) |

| William Teason |

.jpg) |

| presumed William Teason |

.jpg) |

| William Teason, 1959 a droll, ironic design |

.jpg) |

| back cover |

Monday, September 19, 2022

Butcher's Dozens:The Thirteen Best John Rhodes and the Thirteen Best Miles Burtons

Cecil John Charles Street was both John Rhode and Miles Burton, so it's cheating a bit to allow him two sets of bests, I suppose, but then we are talking 140 novels! I think the man deserves it.

Best John Rhodes (all with Dr. Priestley)

The House on Tollard Ridge 1929 classic case of Rhodian murder gadgetry and some good spookery

The Davidson Case 1929 Early use of a famous gambit, which Dashiell Hammett thought unfair, with some interesting philosophical reflections

The Claverton Affair 1933 classic poisoning case in gloomy house with spiritualism too

The Robthorne Mystery 1934 dares to use twins, in violation of Father Knox--can you go to Hell for that?

Poison for One 1934 another classic poisonings

Shot at Dawn 1934 the last word on tides

The Corpse in the Car 1935 yet another classic poisoning with some acute satire

Death on the Board 1937 classic multi-murder case with a multiplicity of ingenious murders, with some acute social commentary

Invisible Weapons 1938 a rare venture into locked rooms

The Bloody Tower 1938 family curses and rural squalor

Death at the Helm 1941 another classic poisoning, with serious treatment of love triangle

They Watched by Night 1941 classic wartime tale

Death in Harley Street 1946 death that is neither accident nor suicide nor murder???

Best Miles Burtons

The Secret of High Eldersham 1930 a classic treatment of the witchcraft theme

Where Is Barbara Prentice ? 1936 high jiggery pokery with a body

Death in the Tunnel 1936 if you want to stage a railroad tunnel murder, this is the way to do it

Death Visits Downspring 1941--wartime mystery; the butler didn't do it but it was done to him

Murder M. D. 1943 (strong character interest in this one)

The Three Corpse Trick 1944 striking complexity in a tiny habitation

The Cat Jumps 1946 one of the early cat mysteries and a locked room situation

Situation Vacant 1946 Why do the secretaries keep dying in the village?

Death Takes the Living 1949 not his most brilliant plot but an interesting look with disgruntlement at post war England

Ground for Suspicion 1950 excellent postwar provincial mystery

Murder in Absence 1954 partially a cruise mystery, though it's a tramp steamer

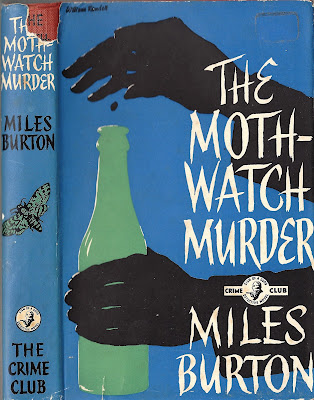

The Moth Watch Murder 1957 notably unique specimen

Bones in the Brickfield 1958 excellent late village mystery involving a found dinosaur fossil

Some More Butcher's Dozens: The Thirteen Best Christies and Carrs

I thought I'd try some more of these, after having done Mr. Symons. These were much harder!

Best Agatha Christies

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd 1926 Poirot--the famous twist, plus good village satire and a great last line

The Murder at the Vicarage 1930 Marple--debut Miss Marple novel, she at her most vinegary, before Christie fluffified her--as a kid I didn't like this one much, but now I love the village satire and the solution is a classic gambit for her

Murder on the Orient Express 1934 Poirot--one of her classic solutions, one of the great train mysteries

The ABC Murders 1936 Poirot--classic serial killer mystery, the best one book with Hastings

Death on the Nile 1937 Poirot--possibly the most purely entertaining Christie--classic boat setting, brilliant solution, strong central characters

And Then There Were None 1939 nonseries--THE enclosed location mystery, perhaps the greatest mystery of them all

The Body in the Library 1942--classic return to St. Mary Mead, in one of her strongest depictions of the village, along with some well-rendered hotel types and another classic solution

Five Little Pigs 1942 Poirot--the best of the more "novelistic" Christies from the Forties, where the emphasis to the solution is based on characters--classic murder in the past treatment

A Murder Is Announced 1950 Marple--perhaps her greatest village mystery (not St. Mary Mead but Chipping Cleghorn)

Ordeal by Innocence 1958 nonseries--Christie deemed this one of her best and authors often get that judgment wrong (!), but this is notable as it looks forward to the rather gloomy, modern dysfunctional family mysteries of PD James and Ruth Rendell, with a solution turning on psychology

The Pale Horse 1961 nonseries with Ariadne Oliver--her best mod mystery, a fantastic mutrder plot with supernatural trimmings that owes a bit to Philip Macdonald

Endless Night 1967 nonseries--a classic psychological crime novel in the modern manner, with a well-rendered angryish young man

Curtain 1975 (written 1940s) Poirot--opinion divided on this one, but I think it's a classic performance, a brilliant finish for a great detective, though it's very much autumnal and the characters by design are a pretty unlikeable lot

Best John Dickson Carrs

The Three Coffins 1935 Fell--highly atmospheric and the locked room lecture, of course, though it gets a bit fiddly in the murders

The Arabian Nights Murder 1936 Fell--impressive essay in multiple narratives, onion like plot

The Burning Court 1937 nonseries--the classic mystery with supernatural undertones (overtones)

The Ten Teacups 1937 Merrivale--review here

The Crooked Hinge 1938 Fell--jaw-dropping solution, whether you buy it is up to you--classic claimant mystery

The Judas Window 1938 Merrivale--classic courtroom mystery, one of Merrivale's best performances

The Reader Is Warned 1939 Merrivale--the insidious idea of teleforce seems to take this in supernatural/sci-fi direction

Murder in the Submarine Zone 1940 Merrivale--classic wartime, shipboard mystery

The Man Who Could Not Shudder 1940 Fell--classic haunted house mystery

The Case of the Constant Suicides 1941 Fell--great Scottish setting with some more supernatural undertones and some lighthearted humor as well

She Died a Lady 1943 Merrivale--one of Carr's best examples of the serious, character-driven mystery from the Forties

He Who Whispers 1946 Fell--superbly shuddery and suspenseful, with providing some strong character interest

The Devil in Velvet 1951 nonseries--Carr's best historical, character driven with a very strong sense of interest and a sinister cameo by Scratch himself

Sunday, September 18, 2022

Butcher's Dozen: The 13 Best Julian Symons Crime Novels

Whenever I post something critical in some way of British author and critic Julian Symons, who died nearly three decades ago, I usually get met with some pushback to the effect of I shouldn't be criticizing Julian Symons, as it just isn't done apparently. It would seem by doing so I am sowing disharmony in the vintage crime fiction community.

I find this ironic since Julian Symons himself fearlessly criticized anyone and anything he felt like criticizing and was so ensconced that it never seemed to harm him in any way. Sure, there was an effort to boot him from the Crime Writers Association, but I gather it gained little traction, and perhaps there were some offended Rex Stout fans, outraged by his criticism of the author and his biographer, who didn't buy Symons' books (though they probably had never done so in the first place); but this was small beer to the esteemed president of the Detection Club and New York Times and London Times columnist.

What I regret is that some people seem to take my criticism of him personally on his behalf. I will say again that it's not personal with me. I like much of Symons' crime fiction and I find him rather a remarkable person indeed (far more so than I am). Obviously he was a very important in the history of his crime fiction, both on account of his fiction writing and his highly personal criticism of the genre.

If you were brought to reading crime fiction on account of his genre study Bloody Murder and it led you on to read John Franklin Bardin and Patricia Highsmith and that Face on the Cutting-Room Floor guy (or better yet, Patrick Quentin), that's all well and good. I wasn't, and I find it a flawed book that contributed greatly to a flawed narrative of the history of crime fiction. However, I don't "blame" Symons for altering the course of crime fiction. Change was inevitable and not altogether a bad thing either.

Incidentally (or not), I have read all of Symons' crime novels and I have enjoyed many of them. My personal favorites are, in chronological order:

Bland Beginning 1949--Symons' essay in Innes-Crispin literary detective fiction, brilliantly drawing on his own family background--not flawless but well carried out and rather charming--reread several months ago and will review here soon

The Thirty-First of February 1950--Symons' first uber-gloomy crime novel, but influential in its deathly seriousness and grim rejection of classic puzzle plotting--influenced by Dostoyevsky, and there's nothing gloomier than a 19th century Russian novelist!

The Narrowing Circle 1954--chosen by Symons' philosophical opponent Jacques Barzun for his 100 Classics of Detection--bears a certain debt to Kenneth Fearing's The Big Clock, but one of S's best examples of a classic mid-century mystery

The Colour of Murder 1957--another classic Symons downer, a study of a downtrodden victim embroiled in a murder case. winner of the CWA gold dagger.

The Progress of a Crime 1960--a documentary style analysis of crime, trial and punishment, which acquainted the UK with the fact that they had police brutality in their country as well; won the MWA's EdgarThe Plain Man 1962--another classic-style mid-century mystery, on the order of Narrowing Circle

The End of Solomon Grundy 1964--another sardonic and ironic murder and trial case, I think better than Progress, but I suppose they didn't want to give him a second Edgar

The Man Who Killed Himself 1967--a dark but droll, twisty inverted mystery, in the manner of Francis Iles

The Players and the Game 1972--one of the classic serial killer novels--Symons wrote a lot of tosh around this time but this is good

The Blackheath Poisonings 1978--Symons' first venture into Victorian mystery, quite good but very gloomy--a classic Victorian family poisoning that likely draws some on his own family history

The Detling Secret 1982--another Victorian mystery, lighter than its predecessor but quite charming--Symons had charm when he chose to exert itDeath's Darkest Face 1990--Symons' venture into Barbara Vine territory and very good too--He died four years later and his last two books show a falling off in quality, but this is superb, one of his very best at age 78--sophisticated mystery at its best.

Something Like a Love Affair 1992--an impressive though slim coda, this one a moving venture into Ruth Rendell domestic morbid psychology

Only one of these books has even been reviewed here, a decade ago now, but I will try to rectify that in the future.

Friday, September 16, 2022

More Great Moments in Julian Symons Crime Fiction History: The Criminal Case of His Cornell Woolrich Criticism

|

| Not Julian Symons again! |

One thing you know if you've read much Julian Symons mystery criticism: He really liked the work of Dashiell Hammett. He devoted four whole pages to Hammett in the first (1972) edition of his genre survey Bloody Murder, a book which modestly runs to under 270 pages.

Symons liked Raymond Chandler too, though he avowed that "it must be said" that Chandler, lacking Hammett's "toughness," "comes off second best" in comparison with Hammett.

All this has to be said," declared Symons redundantly after surveying Chandler's faults as he saw them--verily, Symons was a great sayer of things that that in his view had to be said--yet he allowed that Chandler "was a very good writer." Fair enough!

What's striking to me, however, is how, Chandler aside, other hard-boiled or noir writers from the Thirties fared so vastly more poorly in comparison with Hammett and, indeed, were treated almost as negligible. William Faulkner, a great writer but a crime fiction dilettante, gets an entire paragraph from Symons, but James M. Cain, W. R. Burnett and Jonathan Latimer are confined to one or two sentences apiece, as is Cornell Hopley-Woolrich, as Symons calls him, while many others go unmentioned. Symons backhandedly credits Woolrich with "plots which dazzle by their ingenuity in the half-light of evening, but when the morning comes seem rather contrived," singling out for mention his novels Phantom Lady and The Bride Wore Black.

At his death in 1968, four years before the first edition of Bloody Murder was published, Cornell Woolrich had become something of a forgotten man, though the great French director Francois Truffaut made films from two of his novels in 1968 and 1969. His now long and steady rehabilitation began with the publication in 1971 of the Woolrich short fiction collection Nightwebs, edited by Francis Nevins, but one does not get the impression that Symons was acquainted with Nevins' anthology when he was drafting the first edition of Bloody Murder.

However, in the final edition of Bloody Murder, published two decades after the first, Symons made clear he had read Nightwebs (or at least parts of it)--though the effect of it had only been to prompt him to become further dismissive of Woolrich. People who are aware of Symons' dismissal of the "Humdrum" British detective novelists and some of Britain's Crime Queens (especially Dorothy L. Sayers) may yet be surprised to see the casual dismissiveness with which Symons writes of Woolrich, his great advocate Francis Nevins and the United States in general:

Cornell George Hopley-Woolrich (1903-1968)...is at present a cult figure in America, "one of the greatest suspense writers in the history of crime fiction," as one enthusiast mistakenly puts it....His best writing is in the novels he produced at great speed in the early forties, especially The Bride Wore Black (1940)…and Phantom Lady (1942), but the melodramatic silliness and sensationalism of many of his plots, and the continuous high-pitched whine of his prose--seen at its worst in the collection of stories Nightwebs (1971)--preclude him from serious consideration.

Doubtlessly all this "had to be said," but while my observation which follows here may not truly have had to be said, just let me say it anyway, borrowing a word from Archie Goodwin, as I recollect (at least the television version of Archie as played by Timothy Hutton): As a critic, Julian Symons can be a poop.

What arrogance on his part! One has to wonder what Nevins--the "enthusiast" to whom he patronizingly refers--did to provoke him. I suppose praising Woolrich's writing so effusively.

God knows I have my criticism of Nevins--mainly centering on his calumnies against Woolrich on a personal level and a general attitude which I deem antigay--but the man did do an incredible amount of work on the author and almost singlehandedly revived his work in the Seventies and Eighties. For that he deserves some respect. Symons could not even bring himself to name Nevins in Bloody Murder. Pah! Pfui!

The only effect of Nevins' work on Symons was to cause the critic to downgrade Woolrich further, damning his work as marred by "melodramatic silliness and sensationalism." His comment about "the continuous high-pitched whine of his prose" is one of the nastiest cracks which Symons makes against another crime writer in Bloody Murder.

Certainly Woolrich is not a strictly "realistic" writer like Hammett supposedly is, but this sweeping dismissiveness seems manifestly unfair on Symons' part. I don't really know how well read Symons was in Woolrich--all we really know, apparently, is that he read The Bride Wore Black, Phantom Lady and Nightwebs--but even a reading of some of the tales in Nightwebs (Did Symons not get past the first section?) shows that there is realistic detail to the stories, including a forthright treatment of police brutality and the economic privation of the Depression.

There is also emotional honesty and intensity, though I suppose this is what Symons dismisses as Woolrich's "high-pitched whine." Certainly Symons is not the first person to criticize purple patches in Woolrich's passionate prose, though those particularly sneering words are unique.

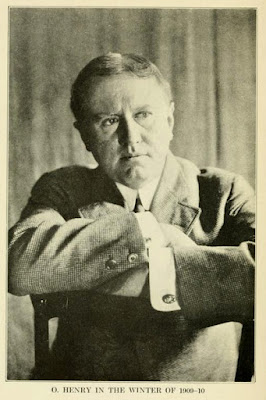

In the end I suppose Symons disliked the emotionalism and artifice of the Woolrich tales, which owe a certain debt not only to Edgar Allan Poe but yet another great American writer, O. Henry. Symons also never thought much of most of the between-the-wars Had-I-But-Known and mid-century domestic suspense writers (mostly women) with whom Woolrich shares an affinity, judging by Bloody Murder, where he deems few of them worthy of inclusion and serious discussion.

Conversely Symons upgraded Burnett and Cain in the last edition of Bloody Murder, crediting them despite limitations with making "considerable contributions to the American revolution in the crime story." It is astonishing to me, however, that Symons could not see the same thing in the case of Woolrich, whose influence on noir in his own work and the many radio and film adaptations made from it seems patently obvious.

Symons seems to have been blinded, not for the first time, by his own strong opinions, which conflict with his job as a genre historian. Personally I don't like the writing of, say, Jim Thompson all that much, frankly, but his influence on the genre obviously was great, whatever I think of his work.

But then Symons is dismissive of Thompson too. He briefly shoehorns Thompson into a discussion of pulp writers from the Thirties, declaring that he was nothing "more than an efficient imitator of other writers in the genre." Thompson, he incredibly concludes, lacks "individuality," making it difficult to tell his work from anyone else's! This would shock Thompson's American fans, though being, I suppose, according to the Symons view, a bunch of naïve American cultists, what would they know? At least Thompson fares better than David Goodis, who gets only two microscopic mentions in the final edition of BM. (Neither is mentioned in the first edition.)

As the years go by, I like Symons less and less as a crime fiction historian, though I do believe his due should be paid to him as a crime writer--he wrote some fine books and even some genre classics--and more generally as a critical essayist. The problem with Symons as genre historian, it has to be said, is that he just could not or would not step back enough from his own personal biases. Bloody Murder needed less of his opinions, in my opinion, and more objective history. There, I've said it.

Wednesday, September 14, 2022

Black Shards from a Broken Heart: Hotel Room (1958) and The Dark Side of Love (1964), by Cornell Woolrich

The consensus on Cornell Woolrich is that in the 1950s his fiction writing went into a steep decline, accelerating after the death in 1957 of his beloved mother, Claire, with whom he had resided at New York City's Hotel Marseilles for the last quarter century. The Thirties and Forties were Woolrich's great decades as a writer, when he produced the short and long fiction that made his name and launched scores of films. There were over 170 (!) crime short stories and novelettes--over 100 of them just in his peak pulp years between 1936 and 1939--as well as eleven novels, including classics like The Bride Wore Black, Phantom Lady, The Black Angel, Deadline at Dawn, Night Has a Thousand Eyes and I Married a Dead Man.

Certainly in the Fifties Woolrich's work production declined precipitously. Often the author mendaciously presented old work as new, albeit after giving it a certain amount of revision. As he himself sank into the torpor of alcoholism, squalor and desolating loneliness, so too did his once astonishing work ethic begin to decay.

In August 1958, about ten months after Claire passed away, Woolrich published a mainstream work of fiction which he had been working on for several years. Entitled Hotel Room, the book was a collection of short stories tied together by the fact that each story is set in the same room, #923, at the fictional Hotel St. Anselm in New York, doubtlessly modeled after Cornell's and Claire's own Hotel Marseilles. The author dedicated the novel to his late mother, calling it "Our Book." An up-to-date photo of a pale and gauntly forbidding Woolrich was included on the back of its dust jacket.

Woolrich's biographer, Francis Nevins, is condescending toward Hotel Room, as only he can be, sneering in his biography:

Woolrich was straining to write significantly....the style is ponderous, laughably overloaded with elephantine metaphors and similes, posturings and preachments....a book that is often positively painful to read.

I don't get Nevins at all here, but then I frequently don't get Nevins on Woolrich, when he puts him down so hard (and occasionally overpraises him). Much of the book is well written, I think, and in any event it's not worse written, in my eyes, than his crime writing, which Nevins professes to adore. Nevins scoffs that "the book wasn't even reviewed in the New York Times," but it was in fact reviewed favorably in many newspapers. Ultimately, I think, the book is not a great success, but it is interesting and successful in pieces, something of a curate's egg, though with more good parts than bad.

Nevins thinks that the brilliant "The Penny-a-Worder" (which Nevins calls--and I agree--Woolrich's best original short story from the Fifties) was cut from the book because the publisher, Random House, wanted all the stories, outside of the framing ones, to be tied in with historical events, If true, as seems likely, it was an unfortunate and indeed rather stupid decision, but there are still several good stories remaining in the volume.

Nevins also cites several other stories that might have been originally intended for inclusion in Hotel Room, including "The Poker-Player's Wife," "The Number's Up" and "The Fault-Finder," the latter of which is non-criminous and was never collected. I hope that it will be someday, though Nevins is dismissive of the tale. Another possible Hotel Room discard was recently rediscovered by Nevins and it was published last year in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine under the title "The Dark Oblivion," impressively netting the author an Edgar nomination, fifty-four years after his death. I have not yet read this story, but I certainly need to do so.

It is worth noting as well that Woolrich's brilliant 1938 mystery story "Mystery in Room 913," aka "The Room with Something Wrong," (reviewed by me here) is set at the St. Anselm too--just a few doors down from the room in Hotel Room. It is a story which graces any crime fiction anthology, but the pure mystery content in it is too high for it to have been included in a mainstream work like Hotel Room.

|

| Hotel Marseilles, New York |

All of the stories in Hotel Room are titled The Night of...., with a specific date attached. The first of them takes place when the hotel opens in 1896. It is one of Woolrich's "Annihilation stories" as analyzed by Nevins, wherein a person seemingly vanishes off the face of the earth, though here the purpose of the vanishing is to not to produce a crime baffler or spine-tingling suspense but rather tragic melodrama.

The vanished person is a young newlywed husband from Indiana, on his honeymoon night at the St. Anselm with his even younger bride. He shyly steps out for a minute to allow her even more shyly to get changed for bed--and we never see him again.

It's a moving tale, achingly evoking the desolation of enforced solitude in a hotel room, something Woolrich himself knew so well; and, if one is so inclined, one also can see in it reflections on Woolrich's own disastrous, extremely short-lived marriage, about which I have written over at Crimereads.

Woolrich's marriage failed, apparently, because he did not desire to, or was unable to, consummate it, leading his frustrated wife to leave him and eventually secure an annulment, after humiliating him nationally in the newspapers, with accounts of how he was a pallid aesthete who adored his wife too much to have sex with her. Woolrich certainly well conveys a couple's nervousness about having sex in the first Hotel Room story. Later on in the story a doctor, speculating on what happened to the husband, avows:

If a boy is brought up in a strict, religious household, and trained to believe all that [sex] is sinful--then his conscience will trouble him about it later on. The more decent the boy, the more his conscience will trouble him....I think this boy ran away because he loved her, not because he didn't love her....

Was this Woolrich's mea culpa on his marriage?

|

| The signing of the Armistice celebrated on November 11, 1918 |

The next two stories, which respectively take place on April 6, 1917, when the U. S. entered the Great War to fight Germany, and November, 11, 1918, when the Armistice was declared, really constitute one story told in two parts. All together it's about a young man and woman who impulsively make a war marriage and ironically come to feel rather differently about the whole thing a year and a half later.

This is a wise and wryly humorous observation of shifting American sexual and generational mores, the sort of thing Woolrich must have written for the romance magazines in the Twenties, though it's more sexually explicit than he could have been in magazines at that earlier time. It does rather remind one of Woolrich's early literary idol, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

For me the snag is in the next two tales, one a violent, nasty crime story taking place in 1924 that really feels out of place here, and the other, taking place on Black Thursday, 1929 at the onset of the Depression, about a man stepping back from committing suicide, that is altogether too falsely peppy. Sad to see "Penny-a-Worder" getting bumped for these two tales!

Woolrich rebounds in the brief penultimate story, which takes place on the eve of Pearl Harbor, which though very short indeed packs quite a punch, at the end. (It's a twist in the tail story.) However, after that we are already at the second half of the framing story, taking place when the hotel closes in 1957, and that's that. The biggest problem with Hotel Room is that it is too short. It definitely could have used the inclusion of "The Penny-a-Worder," not to mention the other excised tales (though I could have done in any case with "The Number's Up," which is almost too cruel and depressing for words.)

One of the striking things about Hotel Room is the sense of human sympathy one senses from the author. Not for the first time, Woolrich is condemnatory as well of nationalism and racial prejudice and I think he has gotten insufficient credit for this as an author in accounts which continually emphasize his many queer hang-ups and phobias. There was a real intelligence in this author and a sense of empathy, although admittedly it often curdled into gloomy, even nihilistic, pessimism.

*******

We certainly see this pessimism in the penultimate collection of short stories published by Woolrich during his lifetime, The Dark Side of Love: Tales of Love and Death (1964), which carries a telling epigraph from the poet Auden: The More They Love/The More They Feel Alone.

Woolrich must have been in a bleak mood indeed when he conceived this slim volume of eight sad and often sexually perverse tales, cheaply produced by back number publisher Walker. The collection received little notice at the time and has a pretty poor reputation, yet in my view it is by no means a negligible book.

"The Clean Fight," which Nevins greatly admires, is a damnably confounding story, and one I personally find extremely repulsive. It's all about how police hunt down and kill a man indirectly responsible for the death of their beloved retired captain's son. (The hunted man was another cop who for a bribe informed on an upcoming police raid.)

The retired police captain, who lives as a gross bedridden alcoholic in a hotel room after suffering a stroke (shades of Woolrich's fate), is an unpleasant character indeed, telling his former men (who bafflingly are still loyal to him to a man):

I want to see him [the informer] lying on the floor, beaten until he can't feel it any more. Then brought back, and beaten some more, and some more, and some more. I want to stamp down on him with my foot myself. I want to spit into his open, speechless mouth.

thwarted hate of the pack when the rabbit has eluded them....and when the pack happens to be the police, unaccustomed to such defiance, this can be a terrible thing. Far better to lose the game than to win it. For it can't be won anyway....one man alone cannot stand against them [the police], no matter how wealthy he is, no matter how adroit or basically non-criminal or legalistically unpunishable.

This does not really sound approving of the police and brutal private avengers, like Spillane, but rather simply resigned to the terrible inevitability of such brutality and its efficacy.

Or was there a masochistic quality in Woolrich himself? Did some part of him like being emotionally hurt, perhaps even literally physically beaten?

Being convinced that Woolrich was gay, Nevins attributed the author's attitude toward the police to a homosexuals' self-contempt (when the police beat up a man in his fiction, you see, Woolrich is figuratively beating up himself for his homosexuality); but perhaps the author simply was a masochist, whether gay, straight or something else yet on the sexual spectrum. Love hurts, as they say, and Woolrich always seemed to make certain that it did in his case.

|

| Please, mum, may I have another? |

This reading seems backed up by another tale in the collection, "The Idol with the Clay Bottom," which is about a prostitute with a heart of, well, brass perhaps, who falls in love with a noble, manly protector named Don, only to learn that, as a result of his upbringing with a blowsy, brutal stepmother, he is in fact a masochist, sexually stimulated by spankings.

This story seems to have been uniformly ridiculed, perhaps because people are nervously uncomfortable with the subject matter, but certainly individuals like the man in this story existed and still exist in this real twisted world.

Woolrich attempted to get this queer story, which he termed Rabelaisian, published as early as 1944, according to Nevins, yet he didn't succeed until the Swinging Sixties.

I actually don't find this a bad piece of fiction, though Nevins primly pronounces it a "wretched waste of ink." When in the story frame the prostitute, Marie Cameron, is asked by a nameless client whether she was ever in love, she replies, resignedly, that she was once, adding: "You can't expect to be that lucky: to have it miss you." The Woolrich philosophy in a nutshell: Love to regret it.

To me this gives the last line of the story a frisson not of romance but of disquiet. The story also includes the memorable line, "shrilled" from our hooker heroine to her disturbed beau: "Geddaway from me!....You're queer for paddy whacks!" Try using that one sometime.

Another, more forgettable tale from the collection, "The Poker-Player's Wife," also has a decidedly masochistic edge to it in the way that the titular spouse self-sacrificingly allows her poker-player husband to treat her. "Je t'Aime," about a Parisian love triangle (or perhaps another geometric formation), is a tale of mild, though murderous, irony, which was originally published the previous year in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, this being the only one of these works, apparently, which the fastidious Frederic Dannay would touch. It comes off almost as "normal" compared to most of the rest of the stories in this collection.

The most bizarre of the stories is "Somebody Else's Life," which originally appeared in teleplay form in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1958. It is a sort of temporal soul transference tale that illustrates a spiritual medium's warning to a French gambling addict countess that

The past is the future that lies behind us, the future is the past that lies before us. Only fools think that they can divide the two in the middle.

Adherents of Nevins' notion that a young Woolrich once donned a sailor suit and roamed the docks in LA in search of male sex partners might be struck by the countess' belief that one can truly alter one's life for the better by donning another person's clothes, but of course the woman's desperate hope comes to naught.

Then there's "Too Nice a Day to Die," a tale greatly admired by Nevins, which is an emotional conte cruel--and then some. It's about a girl who by a quirk of fate decides at the last minute not to commit suicide, then meets a nice boy, then....you see the ending coming a mile off, though you hope against hope it won't end that way. This is Woolrich at his gloomiest, remember.

There are two other stories in this collection that especially struck me: "Story to be Whispered," about a man who murders a male-to-female cross-dresser (or transgendered?), which Nevins, naturally, deems indicative of "Woolrich's contempt for himself." What was it, one wonders, when Mickey Spillane had his psychotic detective hero Mike Hammer murder a cross-dresser in one of his novels?

Yet in "Whispered" is the view of the narrator--or more accurately that of the narrator's defense attorney--meant to represent Woolrich's view, as Nevins apparently thinks, or is the tale simply a depiction of a violent crime, the sort of thing which, unfortunately, occurred all too often in real life (and still does)? It isn't so clear to me as it is to Nevins.

Indeed, the more I think about it, I believe the last line of the story is meant to undercut any notion that the murder of a "queer" is something of no moral consequence--which is precisely the opposite of the conclusion which Nevins draws from the story. Rather than self-hatred and self-contempt, the story, as I see it, is indicative of Woolrich's rueful consciousness of the awful panoply of human tragedy.

Then there is "I'm Ashamed," about the visit which two nice, middle-class, underage boys make one adventurous Saturday night to a local whorehouse and the dreadful consequences which it has for one of them. It's an evocative picture of a bygone era and its mores and the agonies and awkwardness of youth, with some of the plotting skill of his crime fiction. It probably tells us something as well of Woolrich's own sexual anxieties and his problematic relationship with his adored but distant Mexican father, who probably called upon more that one bawdy house himself.

According to a cousin, Woolrich as a child threw a great fit after seeing his father, who was estranged from his mother, in bed with another woman. His feeling towards both his parents, both of whom left him alone so often when he was a child, was extremely needy and dependent all through his adulthood.

Very briefly reviewing The Dark Side of Love in a newspaper, esteemed crime writer Dorothy B. Hughes tepidly advised: "For Cornwell Woolrich fans, yes; for others these eight unpleasant stories are unrelieved by anything but gloom." It's a mostly fair enough assessment, but I am a Woolrich fan, especially of his short fiction, and I am glad to have walked for a time on the dark side of love and longing with this grim volume. Both it and Hotel Room have never been reprinted since their original publications; perhaps it's time that these omissions changed.

|

| A. Rothstein, photographer |

Thursday, September 8, 2022

Forever England

"These English are a pest. Always poking their noses in where they are not wanted....This young man, Smith or whatever his name is...has nothing to gain....Yet he comes here, busying himself. How is one to deal with such people? They are without sense, when you offer to buy they will not sell, they are hard when you expect them to be soft, and soft when you think they will be hard, and somehow by accident, they have acquired an empire."

--Baffled Commendatore Marucci in The Murder of Eve (1945), by Moray Dalton

Wednesday, September 7, 2022

Daltons for December? More Moray Dalton Mysteries on the Way!

Readers who have enjoyed the original ten Moray Dalton (aka Katherine Dalton Renoir) mystery reissues, which include The Belgrave Manor Crime (1935), The Case of Alan Copeland (1937), The Condamine Case (1947) and The Art School Murders (1943), all of which I reviewed here on my blog, should be pleased to learn that, finally, after two-and-a-half years now, we are moving swiftly afoot to reissue six more titles by the author.

Like Annie Haynes, Ianthe Jerrold, Harriet Rutland and Molly Thynne before her, Moray Dalton has been popular in reissue with Dean Street Press and it was the intention to release ten more titles well before now. (The last ones were in the spring of 2020, right around the time Covid struck in the West.) The new titles all are postwar; and, indeed, with the previously reissued The Art School Murders (1943) and The Condamaine Case (1947), will complete all of her 1940s novels, plus her penultimate book from the early Fifties. Four of them are Hugh Collier detective novels, while a pair are non-series.

These "new" titles are:

The Longbridge Murders (1945) Collier

The Murder of Eve (1945)

Death at the Villa (1946)

The Case of the Dark Stranger (1948) Collier

Inquest on Miriam (1949) Collier

Death of a Spinster (1951) Collier

The four Colliers are very enjoyable, indeed, the first three are among her best. The last, Spinster, is a little weaker, I would say, because Collier only appears in the last 10% of the book, in essentially a cameo. The main plotline is quite interesting though.

In Longbridge Murders, Collier appears when the Yard is called in concerning the latest of an unsolved string of murders in the West Country village of Longbridge. Are they connected somehow, the work of a serial murderer? This is a highly intriguing and ultimately moving story, with Inspector Collier performing in it most ably. Of it Jacques Barzun wrote: "Good characterizations and a limited group of suspects make the problem vivid....the work must be rated among Dalton's best."

I reviewed The Case of the Dark Stranger here back in May 2020, when I was expecting Daltons to be released that December. This is a very interesting one indeed, with something like a Barbara Vine temporal structure, with key events taking place in 1892 and 1912.

It's a backward look at a time when Collier was a very young man, a mere detective sergeant, and his superior Superintendent Cardew but a detective inspector. It also draws on the author's deep familiarity with Italy, with some parts of the novel taking place there (though the bulk of it is set in England).

Inquest on Miriam is another mystery set in the West Country, a favored English setting for the author. It takes place in the village of Fallowford, a place dominated by a malevolent, wealthy, old woman named Miriam Oliver, who owns most of the habitation. Or owned, I should say, as Miriam is the subject of the novel's titular murder inquest, which commences in the second chapter.

This is a good old family poisoning murder, with beleaguered innocence and as nasty a lot of relatives as you could hope for (in fiction). Collier's stepson Toby Fleming, now twenty-two, plays a major role in this one, as he works as the private secretary for a gentleman implicated in the case, who seems partly to have been based on the author's father. I'll say a bit more about young Toby later.

Death of a Spinster concerns sinister doings at creepy Jericho House (located in another West Country village, Greensted), which implicate a trio of ill-assorted cousins. This is a very nicely plotted crime novel, though disappointingly Collier essentially makes only a cameo turn in his final appearance. I was rather reminded of Margery Allingham, as well as Agatha Christie.

With these four reprints, Dean Street Press will have reissued not only the first five Collier detective novels (One by One They Disappeared, The Night of Fear, The Belfry Murder, The Belgrave Manor Crime, The Strange Case of Harriet Hall), but the last six of them as well. Unfortunately for the moment this leaves a hole in the middle, as it were, in that the four middle Collier mysteries have not been reprinted yet, and these are the ones where Collier meets Toby and his mother Sandra, the latter of whom whom he romances and marries over the course of two novels, like in the books of Dorothy L. Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, Margery Allingham and PD James. Toby starts off as a schoolboy but is a young man in his later appearances/references. I hope to rectify this matter next year.

Interestingly, Longbridge and Miriam, though they were published after World War Two, are backset in 1939. This means that they take place before the wartime Art School Murders and possibly as well The Condamine Case, which I think is postwar, although I would have have to go back now and reread it to make certain. (Sandra Collier briefly appears in Condamine, but I don't recall mention of Toby--is there mention of them in Art School Murders?) Spinster, however, is definitely set in the late 1940s or 1950.

This leaves the two nonseries novels, both of which are set primarily (Eve) or entirely (Villa) in Italy, a country which Dalton loved and must have frequently visited or even for a time resided as a young woman. It is where she set her first two novels, Olive in Italy (1909) and The Sword of Love (1920).

The Murder of Eve is another one in which the author does some interesting things with time. The bulk of the novel is set in 1905, when Dalton herself was 23. How much did she resemble the 24-year-old Englishwoman heroine of the novel, Miss Lily Oram? Then there's a moving epilogue, set in 1940, where we find out what happened with some of the surviving characters.

Both Eve and Villa are intense stories. There are murder plots and plenteous murders but they are more thrillers, I would say, though in that era this term conjures up unfortunate comparison with Edgar Wallace, who seems, I must say, merely jejune in relation to Dalton. I like Edgar Wallace's fiction well enough, but Wallace was not as emotionally mature in writing, especially in his treatment of women, who tend either to be either sexless good girls or wicked adventuresses. Dalton allows nice women to fall from the pedestal a bit without being damned to perdition.

These two Daltons are really more crime novels, straitish novels with crime and murder and melodrama. Villa takes place during WW2, sometime after the initial Allied invasion of southern Italy and the German military occupation of northern and central Italy, propping up Benito Mussolini as a Nazi puppet, in September 1943. There are two plot strands, one concerning skullduggery at an Italian nobleman's villa, and another about an English RAF pilot downed in the vicinity, and they dovetail beautifully. Jacques Barzun called it a "tense situation, beautifully plotted and narrated," in which "the principal interest lies in the admirably diversified characters and the picture of the times."

I was reminded of that superb French World War Two television series from the last decade, A French Village, and was racing through the last third of the novel, almost chewing my fingernails, to find out what would happen. This book would make a splendid film! They wouldn't even feel the need to change anything to sex it up and darken it a la Sarah Phelps.

I am really pleased to see these books are coming back in print soon. It is common to say that a given artist is underrated, but I do think that has been the case with Moray Dalton. Rest assured, I am genuinely a "big fan" of the author and have been for two decades now.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)