Publisher Carroll & Graf did a lot of neat vintage crime fiction reprints in 1980s and 1990s, including a couple of 1985 Cornell Woolwich short fiction collections, Blind Date with Death and Vampire's Honeymoon. The former I reviewed previously here and the latter I am reviewing tonight for Friday Night Frights.

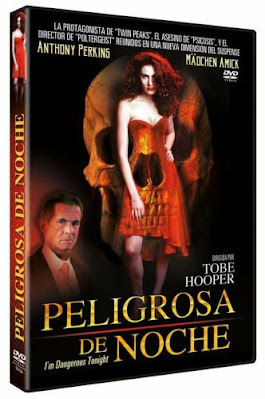

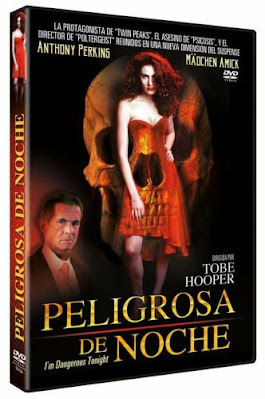

"Vampire's Honeymoon" contains four novelettes: the title story, "Graves for the Living," "I'm Dangerous Tonight" (actually a novella by my count) and "The Street of Jungle Death." By far the best known of these, I suppose, is "I'm Dangerous Tonight," on account of its having been filmed in 1990 as a TV movie by Tobe Hooper, of Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Poltergeist fame. It's the one about the devil dress. (See below.)

On the other hand, Woolrich later expanded The Street of Jungle Death into the excellent serial killer novel Black Alibi (1942), which was filmed by Jacques Tourneur the next year as The Leopard Man, one of the better Woolrich films, so it definitely might seem familiar to you if you read it. The other two novelettes have never been filmed, but certainly they should be entertaining if they were!

Vampire's Honeymoon is the shortest of the tales, at about 10,000 words, though Woolrich later expanded it under the more evocative title My Lips Destroy for inclusion in his short fiction collection Beyond the Night. I don't know that it necessarily benefits from the expansion; in both versions the plot is the same.

With Vampire's Honeymoon, which was published in pulp magazine Horror Stories in August 1939, Woolrich was faced with the basic problem that anyone faces in doing a modern vampire story: How do you portray vampires in an up-to-date setting without seeming hokey?

Ever since Dracula and Hammer horror films, it's hard not to associate vampires with Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee (or maybe Frank Langella) and all the traditionally stage properties: forbidding Gothic castles and frightened, superstitious peasants; crosses and coffins and cloves of garlic; squeaking black bats and heaving Victorian bosoms.

However, Tobe Hooper (him again) pulled it off with his superb Salem's Lot two-part television film, which is set in the state of Maine in the Seventies and still scared the bjeesus outta me in 1979 when I was unlucky age thirteen!

For that shocker, which was based on the bestselling Stephen King novel, Hooper drew on the 1922 German expressionist film Nosferatu, rather than Dracula and its unholy progeny. Yet another good, if a bit cheesy, effort was the Very Eighties film Fright Night (1985), where Chris Sarandon played your classic sexy, seductive bloodsucker to a terrible toothy T.

The Carroll & Graf cover of Vampire's Honeymoon (see above left) depicts Christopher Lee as Dracula about to put the bite on actress Melissa Stribling in Horror of Dracula (1958). This happens to be an inaccurate depiction of the tale, however, for it concerns not a male, but a female vampire, harking all the way back to Victorian author Sheridan Le Fanu's creepy tale Carmilla, without the lesbian subtext.

|

| French actress Catherine Deneuve in The Hunger, a 1983 vampire film |

Vampire's Honeymoon has been routinely dismissed by Woolrich critics, with Anthony Boucher sniffily deriding the tale as "the most tedious arrangement of cliches on the vampire theme ever assembled." Woolrich biographer Francis Nevins sneeringly pronounces it "one of the worst [stories Woolrich] ever perpetrated."

Personally, I don't think it's a bad tale at all, though certainly there's no suspense over what the hell's up with Dick Manning's weird bride. Of course when the publisher of Horror Stories insisted on calling the tale "Vampire's Honeymoon"--Woolrich's preferred title was Blood Kisses--they rather gave the game away at the very start. Was Blood Kisses too sexual a title for the pulps?

Vampire's Honeymoon is a competently told vampire thriller, with some effective shuddery passages. (And, yes, the couple in question does go off on a honeymoon together, in Atlantic City!) Personally, I think the tale has been too quickly brushed off by critics. One interesting point to me is the question of how it might have helped lead to Woolrich writing his great crime novel The Bride Wore Black, which Woolrich completed ten months later in June of the following year.

The scene where Dick Manning--an engineer in New York City enjoying his engagement party at some friends' high rise penthouse apartment with his intended, Sherry Wayne--first meets, on the dim terrace outside the apartment, his future vampire bride, on whose account he promptly dumps Sherry, is strongly reminiscent of the unforgettable terrace scene in Bride Wore Black (unforgivably filmed in daylight in the Truffaut film). Beyond that the vampire, who suggestively calls herself Faustine (see the Algernon Swinburne poem by that name), is a hunter and a slayer of men, just like the remorseless Bride.

In Honeymoon Dick's fiancee Sherry is blonde and unsubtly of the world of light, while Faustine is dark-haired and very much of the night. Nevins makes much of this rather obvious vampire symbolism, choosing to read the story as a parable about Woolrich's half-Mexican father's rejection of his mother and taking up with a series of Mexican mistresses. (Dick is a civil engineer, like Woolrich's father.) Well, maybe, but again, what else are you going to do in a vampire story? Vampires are creatures of the night after all! Also pretty young blonde heroines are routinely featured in Woolrich tales.

Surprisingly to me, Nevins with all his fixation on Woolrich being a "self-hating homosexual" completely fails to see, in Faustine's late night perambulations lustily seeking men to suck, any relation to gay cruising. Ya missed an opportunity here, Mike! Indeed, there's quite a lot of emphasis in this story about neck biting and blood letting, with rather more sexual implication than we usually see in Woolrich.

Another interesting point is that Sherry, who initially seems just a wilting blonde ingenue, actually emerges as one of Woolrich's classic fair avengers. Dick may be a "poor goop" as Nevins declarers, but Sherry gives the story some additional bite!

One can also see an influence on The Bride Wore Black in I'm Dangerous Tonight, a 1937 novella about a literally Satanic dress that turns the women who wear it into to bloodthirsty killers. Now this is a great idea for a shocker (the title is great too) and I can see how it appealed to Tobe Hooper and company.

The novella starts out in France, at a Parisian dressmakers, moves shipboard across the Atlantic and then ends up in New York. The first two murder sequences in the novel are terrific and quite spine-tingling, especially the one on the ship, which is another precursor to the terrace scene in Bride. The problem I have with this tale, however, is that the narrative focus shifts from the murder-crazed women to the stolid New York police detective on the trail of the demonic dress. It becomes more of a detective and less a horror story at that point, which makes little artistic sense to me. If you are going to take the time to introduce Satan into your story, you'd damn well better keep things satanic.

Not surprisingly, the 1990 adaptation of the novella was "loose." It's still a killer idea for a story, however, and you should see the film, which has sexy Madchen Amick of Twin Peaks fame, late character actor R. Lee Ermey, Dee Wallace and, in a small role, Anthony Perkins, who had given up trying to outrun his horror typecasting. Even Natalie Shafer--aka Lovey from Gilligan's Island--pops up for a few minutes, as the invalid grandmother. The frail Shafer must have been nearly ninety when this was filmed and she died from liver cancer the next year.

Anthony Perkins himself would die from AIDS-related pneumonia two years later, after appearing in a few more crime-oriented films, including Psycho IV and A Demon in My View, an adaptation of the Psycho-influenced Ruth Rendell novel, and the TV mystery In the Deep Woods, which aired after the actor's tragic, untimely death at the age of sixty. AIDS cheated us out of at least another twenty years of Anthony Perkins film performances.

There is also an unacknowledged remake of I'm Dangerous Tonight, evidently, a 2020 film called In Fabric, which I have not seen but it sounds interesting. You can't keep a devil in a red dress down!

Getting back to the story for a second, Nevins in another one of his dippy and revolting interpretations of Woolrich suggests that the portrayal of the women who don the devil dress as "murderous psychotics" reflects "the homosexual man's perception of women as Wholly Other." Nevins adheres to the notion that gay men really hate women and can't write about them because they don't *bleep* them, which used to be current among repulsive anti-gay psychiatrists and cultural observers, like sixty or seventy years ago. Back then this was a charge leveled by straight men at gay playwrights Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee, William Inge and our old friend Hugh Wheeler, as they were sternely admonished to stop writing about straight people and stick to their fellow queers. Their heterosexual critics had difficulty seeing them through any other lens than a lavender-shaded one.

I continue to be amazed that this massive compilation of egregious negative queer stereotypes--aka, Nevins' biography of Woolrich--became the final word (purportedly) on Woolrich for over three decades, well into the ostensibly more enlightened 21st century. I can only conclude that most people haven't actually read Nevins' biography, which, to be sure, is extremely long and pretty impenetrable.

When I published my revisionist Woolrich article at Crimereads back in January, I was gratified to find that I wasn't the only one repelled by the outdated--outdated even when the book was published--homophobic attitudes in this book. On the other hand, I recently had an unpleasant disagreement on Facebook with an outspoken gay man in the biz who defended Nevins as simply representing the general view of 1988. I don't think so, my lad! 1988 was not 1968 or 1958. In any event, would he similarly let off the hook the people, including Nevins himself, who kept repeating the Nevins mantra in the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s, into the 2020s? Maybe he would, but I'm not.

The truth is Woolrich, whatever the exact nature of his sexuality, wrote a lot better about women then most of his contemporarily noir and hard-boiled writers, straight men for the most part who often portrayed women dreadfully chauvinistically, even misogynistically. A good chunk of I'm Dangerous Tonight is even written, quite convincingly, from different women's perspectives.

Personally, I think a version of I'm Dangerous Tonight set among drag queens would be interesting, but given today's drag queen bogeyman (or woman) hysteria, maybe not! Don't want to encourage the queer-bashing hysterics out there. Incidentally, if you believe in the sailor-suit-in-the-suitcase story that is so dear to Nevins' heart and that Woolrich liked to cruise the Port of Los Angeles in uniform, as it were, I suppose you could argue that I'm Dangerous Tonight provides evidence of clothing fetishism on Woolrich's part--although as far as I know no one ever accused him of stepping out in a red dress. (Even J. Edgar Hoover wore black, I think.)

|

| killer (?) cat bares fangs in The Leopard Man |

The Street of Jungle Death is an interesting inclusion in this collection, if only because it shows how much Woolrich could improve a novelette when he novelized it. It's about a leopard ostensibly running amok in Los Angeles (!), killing pretty young women. (Hm....)

There are some good, shuddery death sequences in this story, but the novel, reviewed by me here, is so much better than the novelette. Woolrich moved the setting from LA to South America, which makes the whole thing a whole lot more plausible; changed the cat to a jaguar; ramped up the evocative writing and atmospheric terror; and dispensed with attempting to provide rational motivations, which is just as well, believe me. In the process a decent crime novelette blossomed into a great crime novel.

Finally, there's the best tale in this collection, Graves for the Living, which Francis Nevins singled out as the lead story to his landmark Woolrich anthology Nightwebs, published in 1971, just three years after Woolrich's death at the age of sixty-four. Admittedly this is a lurid, outlandish story and I have to wonder whether the frequently stodgy Julian Symons--who with overweening dogmatism pronounced Nightwebs a dreadful collection in his book Bloody Murder--ever even got past this one. It's not characteristic of Woolrich, really, but it's a fascinating tale nonetheless. Despite all my disagreements with Nevins, Nightwebs is quite a good collection of tales, Julian Symons' pronouncement notwithstanding.

Basically Graves is about a damaged young man who runs afoul of a blackmailing cult composed of nuts with obsessions about premature burial--now there's something you don't see every day! But despite the bizarre plot it's really quite scary. There's really a palpable sense of "no escape" here, that the cult is omnipresent and omnipotent and that our hero is doomed. Is he? You must read and see!

Reading this one I was reminded of Mark Robson's The Seventh Victim (1943) and Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby (1968), both terrific films about cults, as well as those splendid grisly old EC comic books from the Fifties, like Tales from the Crypt and Vault of Horror.

And then there's the question of Edgar Allan Poe. Nevins with his penchant for declamatory exaggeration pronounced over and over again that Woolrich was the Poe of the twentieth century, but I don't know that that was doing him any favors. Certainly Woolrich was often gloomy and doomful, like Poe, but most of his tales lack the Gothic trappings of the Master.

Graves for the Living, on the other hand, has the authentic macabre Poe touch in spades--as does another terrific Woolrich tale, The Living Lie Down with the Dead. Both of them, uncoincidentally, concern premature burial, a subject about which Poe certainly wrote a thing or two!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)