And now a little tale of terror for this Halloween, courtesy of Australian author Lucy Sussex, who over the years has detailed so much about lowdown deeds down under.

Also see Bev Hankins' Friday Nights Fright post, which came a bit late but is perfect for tonight, on creepy country houses, here.

Now onto Lucy Sussex's piece on Mary Fortune's "White Maniac"--The Passing Tramp

Many stories lie completely forgotten in the dusty pages of old magazines. Some are truly terrible, others of their time and unable to transcend it, and a few prove to have startling, enduring value. One of these is Mary Fortune’s 1867 “The White Maniac: A Doctor’s Tale”. When rediscovered last century it was of initial interest as a proto-vampire story, though that definition has been contested.

In 2020 it was reprinted in the British Library’s anthology Visions of the Vampire: Two Centuries of Immortal Tales, eds. Sorcha Ní Fhlainn and Xavier Aldana Reyes. This honour is all the more unusual in that until recently the story and its author were totally unknown. Mary Fortune (1832-1911), who wrote as Waif Wander and W. W., was an Irish-born woman who would emigrate to Canada and then Australia. She is best known as a pioneering woman detective writer, producing over 500 stories in the serial “The Detective’s Album, published from 1868-1908).

While concealing her identity and name almost completely (for good reason) she had a forty-year writing career. It included revolutionary poetry, an unreliable memoir, and spirited journalism, but she also worked successfully in the Gothic. Her 1866-7 novel Clyzia the Dwarf is a deliciously excessive melodrama, featuring a deformed Roma woman with a magic snake necklace, which on command comes alive and bites her enemies.

“The White Maniac”, while melodramatic, is a far more compact and controlled piece. Fortune had been writing detective stories for only two years, and the tale is structured like a detective story, a mystery presented, with a truly creepy revelation.

Despite Fortune living in Australia, the story is set in London.

The narrator, young Doctor Elveston, is intrigued by the “white mad people in

his locale”, foreigners whose house and dress is monotonous white only.

Even

when he ascends a belfry to snoop over the high walls, all he sees is “glaring

and sparkling gravel” and marble statuary, everything pure white.

In the usual coincidental way of Victorian

narratives, Elveston is consulted by the head of this bizarre household, a

French Duke. His niece Blanche, Princess DÁlberville is in failing health, not

least from insanity. All colours, particularly red, have to be kept away from

her, lest she suffer “uncontrollable agitation”.

As

a consequence she lives in a world of white: “…one can scarcely conceive the

strange cold look the utter absence of colour gave it. A Turkey carpet that

looked like a woven fall of snow; white satin damask on chair, couch, and

ottoman; draped satin and snowy lace around the windows…I shook with cold as I

entered it.”

Elveston finds the lady frail and wan, but perfectly

sane. She insists she is imprisoned by her maniac uncle. For those thinking of

Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper”, Fortune was decades in

advance; and a century before Angela Carter, whose “The Company of Wolves” the

tale most closely resembles, particularly in its colour symbolism.

Fortune was an unconventional woman for her time, a

feminist journalist, bigamist, and the mother of an illegitimate son who grew

up to be a career criminal. The male persona she uses in her detective and

other stories (such as “The White Maniac”) allows her to treat ‘indelicate’ subjects

such as rape explicitly, something not permitted to women writers.

Here is unsaid is what is the clear diagnosis for

Blanche: amemorrhoea, absence of menstruation. Contemporary medical men, such

as George Man Burrows, termed menstruation “the moral and physical barometer of

the female constitution” (Commentary on Insanity, 1828). Another

authority, John Millar, proclaimed that “Mental derangement frequently occurs

in young females from Amenorrhoea” (Hints on Insanity, 1861). He

suggested it might be cured with leeches to the pubis.

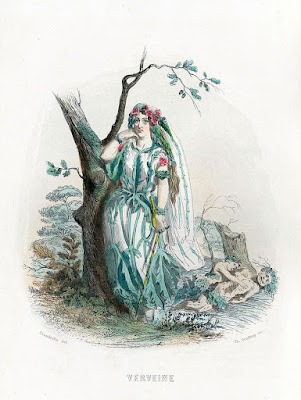

Elveston falls in love with Blanche and decides to determine just who is mad. Being a man of science, he tests with a large nosegay of scarlet verbenas, presented to Blanche.

SPOILER ALERT

…there was a rush, and white teeth were at my throat, tearing flesh, and sinews, and veins; and a horrible sound was in my ears, as if some wild animal was tearing at my body. I dreamt that I was in a jungle in Africa, and that a tiger, with a tawney coat, was devouring my still living flesh, and then I became insensible.

I read this story aloud at a spooky story literary event, where I was obliged to follow a well-known rock star. Being prepared, I armed myself with the reddest flowers I could find, and as I began to read this paragraph, tore them apart. It worked very well. Strictly speaking, the word vampire does not appear in the story, rather ‘anthropopagy’, cannibalism.

However, the symbolism of the blood does situate the story in the vampire canon—and in its use of the female vampire it predates Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla” by four years. The story has attracted interest from film-makers, though never committed to the screen yet. Oh, Netflix! But it shows how an unknown story, by an author nearly lost to literary history, can rise from the dead and stalk our imaginations most powerfully.

No comments:

Post a Comment