One never rises so high as when one does not know where one is going.--Oliver Cromwell

--highfalutin' but entirely apt epigraph to S. S. Van Dine's The Gracie Allen Murder Case (1938)

On April 11, 1939 bestselling mystery author S. S. Van Dine suddenly collapsed and died at his swanky art deco apartment at 241 Central Park West, Manhattan He was only fifty years old, but he had been suffering from heart disease (compounded by chronic drinking) and looked at least fifteen years older than his actual age.

At his death the author left behind an early draft of a Philo Vance detective novel, The Winter Murder Case, which he had intended to serve as a film vehicle for Norwegian ice skating star Sonja Henie; and it was in this stripped form that the manuscript was published later that year in, appropriately, the winter. Of actual novella length only, the book as published misses the usual affected Philoisms that people either love or hate and it is, all in all, a rather pallid work. The Kansas City Star sadly deemed it a "sorry sort of farewell."

|

1931 art deco apartment building where

S. S. Van Dine passed away in 1939 |

However as I recollect The Winter Murder Case, it's better altogether than Van Dine's The Gracie Allen Murder Case, the penultimate Philo Vance mystery, published a year before as a vehicle for the 1939 film of the same title which starred comedienne Gracie Allen, wife of her comedy partner George Burns. It's a bizarre and not very successful novel, in my view, either as comedy or mystery, or comedy-mystery. As a Philo completist I'm glad I finally read it, but I can't say I was impressed.

As a kid in the late 1970s I certainly knew about George Burns, whose career at nearly the age of eighty had been rejuvenated when he won an Oscar in 1976 for his charming role in the film The Sunshine Boys.

Burns remained a familiar presence in American entertainment, finally expiring at the age of 100 in 1996. All I knew about Gracie Allen, his late wife, however, was that she was, well, his late wife. Allen died back in 1964, before I was born, but Burns actually had played straight man to her in their comedy pieces on radio/television in the Thirties, Forties and Fifties.

In fact Gracie Allen was a very big star, though not so much on film. Straight man Burns was then best known for imploring Allen, after listening lengthily to her daffy rambles, to "Say good night," which has generally been popularly remembered as "Say good night, Gracie."

|

| entrance to 241 Central Park West, where S. S. Van Dine died |

S. S. Van Dine, on the other hand, had made a big thing out of film with his mysteries. Philo Vance was a famous film detective, particularly in the incarnation essayed by actor William Powell in The Canary Murder Case (1929), The Greene Murder Case (1929), The Benson Murder Case (1930) and The Kennel Murder Case (1933). The latter film is considered the peak Philo Vance flick and the 1933 book of the same title upon which it is based is well-regarded as well--in fact it's often seen as the last hurrah of the Philo Vance detective novel series.

Van Dine published four more Philo Vance novels between 1933 and 1936--The Dragon Murder Case (1933), The Casino Murder Case (1934), The Garden Murder Case (1935) and The Kidnap Murder Case (1936), but these are generally seen as inferior to their predecessors, as are the films which were adapted from three of the books. After losing William Powell as Vance--symbolically Powell eschewed Philo to become Nick Charles, the detective in Dashiell Hammett's Thin Man series of films--the remaining pictures went through a succession of Vances (Warren William in Dragon, Paul Lukas in Casino and Edmund Lowe in Garden) who never really caught on with the public. A film was not even made of The Kidnap Murder Case, even though it should have been readily filmable.

|

| determinedly art deco lobby at 241 Central Park West |

This was a problem for Van Dine because he and his second wife--he had rather callously discarded his first spouse--were high livers and needed the revenue from the Vance films to maintain their accustomed lifestyles. This is how the strange mashup between Philo Vance--a stuffed shirt if ever there were one, even if the shirt was lavender with a green carnation--and zany stage "nitwit" Gracie Allen came about. "Screwball" comedy was popular in the Thirties and humorous bits often were often incorporated into mystery films, albeit with wildly varying success. If Van Dine--and Philo Vance--had to suffer the Gracie Allen stage persona in order to get back in film, so be it.

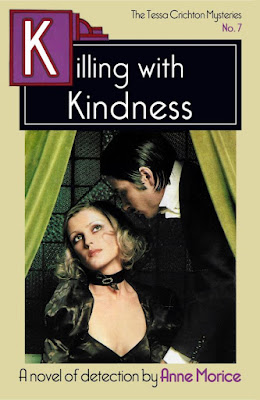

|

Gracie Allen "takes a back seat" to no one--certainly not Philo Vance-in the film version of

The Gracie Allen Murder Case |

Hence The Gracie Allen Murder Case, which appeared in print in November 1938 and on film the following the year, a few months after Van Dine's untimely death. As I understand it, the film version differs significantly from the book; and I can't say that surprises me, because in the book ditzy Gracie very much plays second fiddle to Philo, which is not how the filmmakers wanted it. Van Dine is often condemned for prostituting his creation for film, but in the book he evidently tried to some extent to preserve Vance's integrity (and his). The problem is, you just can't do this with Gracie Allen hanging around.

Never before in his books having evinced any real sense of humor (to the contrary, the books are, whatever you think of them, rather on the pompous and portentous side), suddenly Van Dine is doing these comic bits for Gracie Allen and trying to get us to believe that Philo Vance finds this "girl"--who in real life was 42 years of age and admitted to 36--to be this simply delightful and enchantin' wood nymph and dryad and elf and suchlike, don't you know. Not buying it, SSVD!

Heck, I'm much more tolerant than Philo Vance ever was and even I find Gracie Allen intensely irritating, at least on paper. You really need Gracie Allen in person, I think, to make the Gracie Allen persona bearable. On paper it's just dire. (George Burns appears in the book too, by the by, and is so straight a straight man you can barely see him; he's almost as invisible as Van Dine's ghostly narrator Van.)

|

certainly the author died but he wasn't laughing

Gracie Allen with Philo (Warren William) |

You can tell that S. S. Van Dine was not really comfortable with the Gracie Allen material. He's more at home in the Gracie-less portions of the book, which read like a typical Van Dine detective novel, just not a good one, unfortunately. Weirdly Van Dine has grafted Gracie and George and this perfume company they work for (the In-O-Scent Corporation) onto this rather darkish plot about gangsters and assorted fiends who habituate at the symbolically named Domdaniel nightclub in New York.

There were gangsters in The Kidnap Murder Case as well and it's clear that Van Dine had been trying to toughen up the Philo Vance series, which had been eclipsed by Dashiell Hammett and other hard-boiled boys.

So why drag Gracie in to tag along on Philo's cases now? The answer obviously is the author saw a chance for some desperately needed $$$$!

Unfortunately the actual mystery doesn't work well either. There's really not time to develop much of a puzzle plot in a novel of only around 50,000 words by my count, with much of the wordage given over to alleged Gracie Allen humor. But here goes....

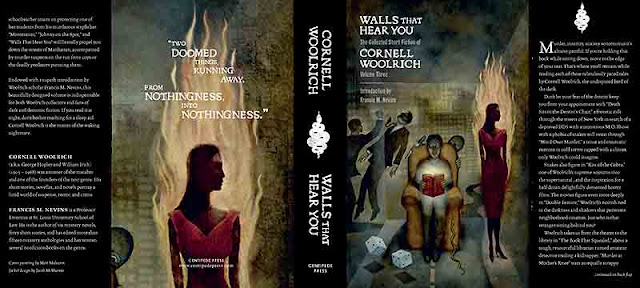

|

Milton Bradley even introduced a

Gracie Allen Murder Case board game to cash in on the film

even though Gracie had no "Clue" as it were |

It seems that an escaped gangster, Benny the Buzzard (aka Beniamino Pellinzi) may be on his way to New York to revenge himself on Vance's pal (and longtime stooge) District Attorney Markham. Benny is connected to the criminal coterie at Domdaniel, which is led by nightclub owner Daniel Mirche, chanteuse Dixie Del Mar and fatalistic philosophizin' crime kingpin "Owl" Owen.

A dead body is discovered at Domdaniel, in Mirche's office no less, on the night when not only Philo and Van were there but, coincidentally, Gracie Allen, boyfriend George Burns and another swain of Gracie's, Jimmy Puttle, who is even more thinly characterized that Burns. Earlier Vance had met Allen, apparently entirely coincidentally, out strolling along Palisades Avenue in Riverdale in the Bronx. In fact there a lot of coincidences in this book, which would be intolerable in a straight mystery, but this thing is anything but.

|

these guys became important players in

Van Dine's last fully completed mysteries,

The Kidnap Murder Case and

The Gracie Allen Murder Case |

Vance solves the case only through Gracie's discoveries, all of them made accidentally, Gracie basically being what at this time they euphemistically called a "natural" in English village mysteries. (There was another name too, much less polite.)

The murder is a sort of locked room problem, except that Van Dine resolves this puzzle through a feckless mechanism much favored by loopy American mystery writer Carolyn Wells; and there's an additional twist which, while clued, seems absurd.

Basically the mystery is very simple, with some hot air--or overheated red herring--thrown up to obscure things.

The laziness of it all is evident in the fact that Rosa Tofana (aka fortuneteller "Delpha") and criminal hubby Tony Tofana, two of the characters in the book--they're listed in the cast of characters at the beginning--do not actually ever appear, although they are frequently referred to by others and play an important role in the plot. I guess that beat actually attempting to characterize them!

A contemporary reviewer of the novel in the Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader, publihsed under the heading "New Philo Vance Yarn Gives Critic Pain in the Neck," roasted Philo and Gracie alike, asserting that the book fell flat between two stools, being neither "goofy enough for Gracie nor good enough for Vance," and resultantly "neither entertaining as nonsense nor interesting as a mystery." The only actual mystery in the bemused reviewer's eyes was "why the Scribners published it."

|

Otto Penzler's 1994 edition

of The Gracie Allen Murder Case

generously included in his

Classic American Mystery Library |

Nevertheless, the book provides some vintage Philo moments for fans, like when the amateur sleuth again expresses his ardent support for vigilantism, a topical subject right now. About the escaped convict Benny the Buzzard, Vance scoffs to proper lawman Markham:

Ah, your precious law and its prissy procedure! How you Solons complicate the simple things of life! Even if this red-tailed hawk with the operatic name should appear among his olden haunts and be snared in Sergeant's seine, you would still treat him kindly and caressingly under the euphemistic phrase "due process of the law." You'd coddle him no end....

And this was uttered in 1938, before the massive criminal procedural reforms imposed by the Warren Court! What would Vance say today? I'm guessing his Twitter feed would really have been something, assuming he wasn't kicked off Twitter entirely.*

*(Of course with all those five dollar words--fifty dollars with inflation--Philo likes to use, he would have had a hard time limiting himself to 280 characters.)

There's one rather odd, essentially extraneous chapter, highlighted by Van Dine's biographer as I recall, where Vance philosophizes about death and the utter ennui of life with the doomed crime kingpin Owl Owen, who only has a short time left to live, afflicted as he is (like the author) with terminal heart disease.

Although Van Dine later condemns Owen as a "diseased maniac" and a "mental, moral and spiritual leper," the high-toned crook sounds a lot like the author, who in his former, financially unsuccessful life as Willard Huntington Wright (before he reinvented himself as a detective novelist) was a prominent aesthete, critic and intellectual.

|

Gracie Allen investigates! (perhaps how co-star

Kent Taylor--playing "Bill Brown," a character

not in the book-- got his mustache so thin) |

"Owen began speaking now of old books, of his cultural ambitions as a youth, of his early study of music," the narrator, Van, tells us. How are we not to connect this with the author himself, substituting painting for music?

When Owen speaks of "the cosmic urge to play a game with life, in order to escape from the stresses and pressures of the finite," is he expressing the author's rationale for having abandoned intellectual criticism for detective fiction?

And when he laments that "Nothing has the slightest importance--not even life itself," is he expressing the author's own despair with living and his knowledge that he too soon will be gone, mere dust in the wind, as the song says?

In any event, what in the world is this downer of a chapter doing in the same book with kooky Gracie Allen? It's discordant in the extreme. Van Dine knows it, because he has "Van" self-consciously introduce Owen by saying "That night...I could not, by the most fantastic flight of my imagination, associate him in any way with the almost incredible and carefree Gracie Allen." Indeed! Nor could I, even when the book was over.

Despite the author's attempts at inducing chuckles--and knowing what I do of the prospect of impending death which he faced--I find The Gracie Allen Murder Case rather a sad book.

That's why I was happy to see Van, Philo's pal and loyal chronicler (and longtime companion), on page one stating that he and the perspicacious and pretentious amateur sleuth had recalled this case together, "as we sat before the grate fire one wintry evening, long after the events." I like to think that these two most confirmed of bachelors enjoyed a happier life together than Van Dine evidently ever did with anyone in his own restless and unsatisfied earthly existence.