"Give Me One More Song to Go." --"Blue Letter" (1975), Fleetwood Mac

Three years separate Ross Macdonald's penultimate Lew Archer detective novel, Sleeping Beauty (1973), from his final one, The Blue Hammer (1976). During these years Macdonald's affliction with Alzheimer's Disease, from which he began showing symptoms as early as 1971, the year The Underground Man was published, worsened. After 1976 he was unable to get another novel off the ground (although he completed a never used screenplay for his novel The Instant Enemy in 1978) and by late1980 he could no longer compose letters. He stopped recognizing people the next year, and in late 1982 he was placed in a care home, where he lived for seventh months until his untimely demise at the age of 67.

|

| Black Lizard edition of Blue Hammer |

Alzheimer's and dementia are tragic at any age and with any person but it's especially poignant in the case of a celebrated writer who started suffering from the disease so early in life, as early as the age of 55. Alzheimer's ended RM's writing career and finally his life, but how did it impact his final books? His biographer, Tom Nolan, says there is evidence of RM's affliction in the last book, The Blue Hammer. He notes that a high school teacher wrote RM a letter pointing out narrative errors in the book. RM thanked him and asked him to proofread his next Archer opus, which of course never came. Earlier California crime writer William Campbell Gault had at RM's request proofread the book and suggested numerous and substantial edits, which RM without demur made. RM dedicated the novel to Gault.

Another friend who saw the manuscript, Robert Easton, "was shocked to find uncharacteristic lapses in tone and diction," Nolan imparts, and "he suggested various revisions in word choice and structure," all of which RM made, again without complaint--very unusual for a writer!

I haven't read The Underground Man yet (one of three RMs left that I haven't read), but I have read RM's last two and I can say that, while I found Sleeping Beauty mostly a chore to get through, it was not the slog that The Blue Hammer was. Hammer is certainly not the equivalent of the last novel that Agatha Christie wrote, Postern of Fate (1973)--a disastrous book though one oddly winsome in its sheer dementedness (I use that last word advisedly, since the octogenarian Christie seems clearly to have been suffering from dementia when she wrote it, as speech experts have since argued)--but to me Hammer obviously is the work of an author with failing power: not the power to conceive a complex narrative, but the power to carry out and complete it.

"I Owe It All to Agatha Christie, and Arthur Conan Doyle...."--"I Owe It All," Something's Afoot (1972)

1974 saw the publication of Ross Macdonald Selects Great Stories of Suspense, which included four crime novels, including Agatha Christie's Miss Marple saga, 4.50 from Paddington. During the time when RM was putting the book together he corresponded with his intimate pen friend and highbrow fan girl, author Eudora Welty, about the project, discussing with her what authors merited inclusion in the tome.

Both RM and Welty, it turns out, were Christie enthusiasts. RM wrote Welty in September 1973:

I'm sorry (for my own sake) if I gave the impression that my anthology will exclude detective stories. On the contrary, it will probably include a Christie (what do you think of is Miss Marple? I like her, and as of now propose to use What Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw [the American title of 4:50 from Paddington], which moves beautifully.) and, if I can get away with it, include a Margaret Millar [RM's crime novelist wife].

Margaret Millar was another cunningly twisty plotter. Welty shared RM's admiration for Christie, writing RM:

Yes, I do like What "Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw"--that's the train one, isn't it--also I like "Mrs. McGinty's Dead"--do you remember that's Poirot and Mrs. Ariadne Oliver--Christie is endlessly diverting to me.

|

| endlessly diverting |

RM and Welty found occasion to discuss Agatha Christie again on the occasion of the Queen of Crime's death in January 1976.

Welty:

Just now I heard on the news that Agatha Christie has died. Was she a friend? I remember hearing from Elizabeth Bowen, who came to know her well, what a marvelous person she was. She really was an era all in herself, wasn't she?

Macdonald:

No, I never knew Agatha Christie except through her books. I think she wrote well, don't you? People I know who have known her have nothing but praise for her courtesy and goodwill. She was even modest.

How, in contrast Christie was, RM might have been thinking, with Raymond Chandler, who in his correspondence notoriously termed RM an imitative "literary eunuch." (Ouch!) In a series of interviews with RM that Rolling Stone writer Paul Nelson conducted in 1976, the year The Blue Hammer was published, RM, who bittelry felt Chandler's derision, at one point exploded, when being questioned about Chandler, either "Chandler tried to kill me!" or "Chandler tried to murder me!" according to varying recollections. (Nelson at RM's request erased his outburst from the tape.) These interviews with RM, which are fascinating, were published in 2015, the centenary of RM's birth in a lovely coffee table book entitled It's All One Case (drawing on a line from The Zebra-Striped Hearse).

The Blue Hammer appeared in July of 1976, about six months after Christie passed away, and, when reading it for the first time recently, I was struck by how much it resembled a Christie novel in terms of plotting, if not in tone. There are even specific echoes of what were several then-recent Christie novels, the author's last several books:

SPOILERS

Nemesis (1971) (long buried body in greenhouse)

Elephants Can Remember (1972) (murder in past, siblings and impersonations)

Postern of Fate (1973) (more murders in the past, along with repetitiveness in the telling)

END SPOILERS

There's even, to go back to a much earlier Christie book, a mysterious man in a brown suit. The exact words "the man in the brown suit" are even uttered by Lew Archer, specifically recalling the title of that 1924 Christie novel. Were these deliberate nods from RM, or, considering his declining mental state, could they have been unconscious borrowings on his part? He had been thinking a lot of late about Christie and her work.

"I've worked on several dozen murder cases, many of them involving multiple murders. And in nearly every case the murders were connected in some way. In fact, the deeper you go into a series of crimes, or any set of circumstances involving people who know each other, the more connectedness you find."

"I don't know what you're talking about."

"I'll be glad to explain. It may take a little time."

"I don't quite follow that."

"It's a fairly complex chain of events."

I sat in my car in the failing afternoon and tried to straighten out the case in my mind.

--Lew Archer Investigates in the The Blue Hammer

|

| His newest--his best yet-- his coast-to-coast bestseller |

While Raymond Chandler is seen, not altogether fairly, as a slapdash plotter who cared nothing about plotting, terming it disparagingly "coolie labor," RM loved plotting. Indeed one might argue he loved it too well.

Sometimes RM's plotting strikes me, in its very ingenuity, as fundamentally odds with his serious intent as a writer. The plot of The Blue Hammer might have been a lovely adornment in a Christie novel, but in an ostensible "serious novel" which has "transcended the mystery genre," as RM's later novels were said to do, I think its problematic.

I don't see how The Blue Hammer can be said to transcend the genre when its ingenious, although frankly implausible and even absurd plot, drags it back down again into fairyland of classic detective fiction.

It is, indeed, the sort of baroque plot you might have found not only in a Christie but in early period Ellery Queen; and that is about as far removed from reality as imaginable, at least in Anglo-American mystery. Golden Age detective novels often are accused of being filled with cardboard characters, plot puppets whose strange fates no one can really care about. Well, in my view there is not a single memorable character in The Blue Hammer.

All of them wear masks which come from RM's by now very familiar box of stage props. There's the boneheaded, angry father, the discontented, frigid wife, the misunderstood and confused boy and girl. I didn't care about any of these people. To be sure, the book does have serious intent, but it doesn't have living characters, rather a ghastly company of drear, dysfunctional ghosts and zombies. Christie's characters, often much criticized (though not by RM), live far more than RM's, at least in this book.

RM's writing is flatter and grayer than it was in the past too. I went back and compared the writing in The Blue Hammer with that in his third third Lew Archer detective novel, The Way Some People Die (1951), one of RM's supposed synthetic Chandler imitations, and the comparison does not favor The Blue Hammer. The prose in Die moves and scintillates; that in Hammer stumbles and bumbles and only very occasionally flashes. And there is such repetition, with Archer and other characters continually repeatedly basic plot points, as if the author himself needed reminding of them, or had forgotten that he had mentioned them. (Granted, the plot is very involved.)

[My son William has] been dead for over thirty-two years," says a character on page 213, before repeating "My son William died thirty-two years ago" on page 215. These repetitious conversations seem interminable, numbing the reader like Novocain. At least they did this reader.

Characters keep expressing their confusion to Archer, recalling eldelry Tommy and Tuppence Beresford and the other characters in the last novel which Agatha Christie wrote, Postern of Fate, composed by Christie when she clearly was in a state of senile decay, as they used to say in vintage mysteries. Granted RM manages, unlike Christie in Postern, finally to clear things up--more or less--but this is not to say he plausibly explains. He doesn't.

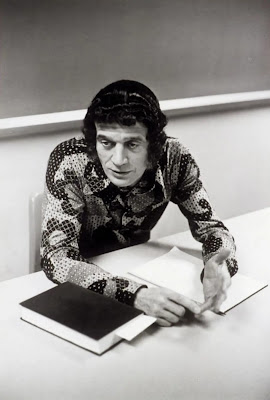

In his pan of the novel at the time it was published, New York Times Book Review critic Anatole Broyard wrote:

|

| Anatole Broyard |

A fully imagined character is not altogether at the disposal of his creator. He acquires a certain autonomy, based on qualities attributed to him by the author, who often unconsciously makes him richer and more complex than he had originally planned. This is one of the elements that makes good fiction an adventure for the author as well as for the characters and the reader.

In "The Blue Hammer" by Ross Macdonald, things are just the other way around. Anyone can be made to do just about anything....To try to unravel this Chinese box of circumstance on the evidence of anyone's motives--the classical way to read a mystery novel--is impossible. You just have to wait until Mr. Macdonald tells you why so and so did such and such....

The novel is compulsively tied up in an almost endless series of knots. Mr. Macdonald's motto seems to be: Give them enough rope and they will knot it. This does not, however, have the effect of making his people complex: They resemble, rather, a group of birds--parrots, perhaps--mindlessly beating their wings against the cage of the plot.

Broyard outlines myriad implausibilities in the plot, spoiling a great deal of it along the way, for shame. Yet I have to concede his points: I agree with him. I found there was ingenuity to The Blue Hammer, but an almost total lack of plausibility. This might not be a problem in a classic Ellery Queen novel from the early Thirties, an era when many still proudly prized ingenuity over plausibility (actually, though, I think it would be a problem there too); but in a sober novel from a writer boosted as a serious and significant American novelist with important things to say about the human condition, it is, I think, fatal.

Let me outline the murder plot of RM's book below, with SPOILERS galore, be warned:

There were these two half-brothers in Arizona, Richard Chantry and William Mead, sons of copper magnate Francis Chantry. William is the illegitimate son of Francis (but see below) and Mildred Mead, an artist's model who apparently had sex with half the men in the state. Both men were artists and Richard, while William was away during World War Two, stole both William's work and his "girl," Francine, and then, when William returned in 1943, murdered him for good measure. Then Richard married Francine, who apparently knew about the murder, and moved with her to Santa Teresa, California, where he carried on painting and became a local hero.

Then in 1950 Gerard Johnson, an old army buddy of the late William, paid a visit on Richard with William's widow and son in tow, apparently with suspicions about William's death. Richard killed him and buried him in his greenhouse. Francis knew about this evidently, as well as their swarthy manservant Rico. (I don't believe we ever learn his last name.) Then, "as if in penance," Richard staged his disappearance to live, as a virtual prisoner at a house in the same town, as Gerard Johnson, a drunken recluse, with William's widow, Sarah, who knew about the murder (s) too, and her son Fred. Wait, what?

|

| What the hell--I mean, heck-- I just don't get it! Gee whiz, those people were nuts! |

Okay, let's keep going. Richard kept painting in seclusion and I think around 1963 produced a "memory painting" of Mildred Mead, which at some point was bought by a Ruth Biemeyer, the unhappy wife of Jack Biemeyer, a Chantry relation who took over running the Chantry Arizona copper mine until he retired, moving with Ruth to Santa Teresa. This couple has a daughter, Doris, a drugged out college girl flower child who has taken up, kinda sorta, with Fred, a professional student type who works at the art museum.

Fred steals the memory painting because he somehow intuits that it might be a Chantry and he "unconsciously" intuits that his father, who painted it, might really be Richard Chantry; and he wants definitively to identify it. (Query: How?)

Crafty Richard, however, steals the painting back and also, while he's about it, kills two men, art dealer Paul Grimes, and artist Jacob Whitmore, who were involved in purchasing the painting from Sarah Johnson and selling it to Ruth Biemeyer, in order to protect his identity. (Query: Do memory paintings hold up in court as proof of murder?)

Ruth bought the painting, by the way, because her husband had slept with Mildred Mead too--who hadn't?--and she unconsciously wanted to guilt trip him by hanging it on the wall. Wait, what?

Have you followed this so far? Let me know if I got something wrong. It's possible! But wait, there's more. RM typically produced last minute twists in his books and there's one, or two, here: Richard Chantry, aka Gerard Johnson, has really been William Mead all along! It seems he murdered Richard back in '43, rather than vice versa. And, brace yourselves people: William is really Jack Biemeyer's son!

In the last pages of the book, Jack and Archer go visit William in jail, where William tearfully acknowledges that, yup, he's William! Fade to black, or rather blue.

The last line of fiction that RM ever published is "Jack Biemeyer stepped forward and touched his son's wet face." I guess this is supposed to be moving. I was thinking, rather, about how William killed four--I think it was four--people, not to mention kidnapped Archer's new (first?) girlfriend, pretty newspaper writer Betty Jo Siddon and tied her naked in a chair in an attic while he painted her picture. (Don't ask.)

END SPOILERS

Frankly, my reaction to this book is that it's all rather silly. It doesn't help that the telling is so repetitious and dull. There's another part of the book where RM gets off on a discussion of the reputed bisexuality of several of the male characters (I lost track), which has nothing to do with the rest of the book and goes precisely nowhere. Is it supposed to be a red herring, or was RM just exploring his sexual issues, like he did his daddy issues and wife issues and daughter issues and grandson issues? Granted, the man had a lot of issues! In previous books he was better able to absorb them into the narrative in an entertaining and illuminating way, however.

RM also introduces a few minor black characters, in an attempt to diversify his fictional world of mostly lily-white wealth. Probably aware on some level that this might well be his last novel, RM also narratively bookends Hammer with his first Archer mystery, The Moving Target, an altogether better book, synthetic Chandler or not. A couple of times Archer mentions his (justifiable) killing of a character in Target, contrasting his violent past with his pacific (and duller) present. There's also a visit to a kooky mountaintop religious cult like the one in Target, where it had much more point and purpose.

This is a better finish for an author than Postern of Fate was for Christie or The Hungry Goblin for John Dickson Carr, to be sure. The swansongs of longtime prolific mystery writers often are sadly disappointing, and The Blue Hammer, in my view, is no exception. What is exceptional are the raves which The Blue Hammer received from critics and the nearly 50,000 hardcover copies it sold.

|

| Eudora Welty |

Eudora Welty, probably RM's number one fan, gushed to him of the novel: "I applauded it all. It was an interesting subject and I thought you made the painting story and family story and murder story astonishingly believable in their multiple connectings and connections." Welty observed that "you were allowing yourself a little freer reign, more ease of the old strictness...and more scope. and more length"--a charitable way of describing the meandering, repetitive narrative.

English Crime writer and critic Julian Symons, a transatlantic friend of RM, told RM that The Blue Hammer "was your best book for a long time, and one of the very best you've written."

For his part, HRF Keating, another English crime writer and critic who often echoed Symons in his critical judgments, included the novel in his book Crime & Mystery: The 100 Best Books (1987), pronouncing it "in many ways...the peak of [RM's] achievement." What a damning thing to say about his earlier books!

I do agree with Keating that "the blue hammer" image which gave rise to the book title is a moving one and beautifully written (although irrelevant to actual mystery plot). However, this is a couple of sentences out of a very long and tiring narrative.

I'll have something to say about a much better RM book soon. The Blue Hammer also made me want to take another look at Margaret Millar's Ask for Me Tomorrow, an altogether better book which she published the same year, 1976, as her husband published Hammer. The fact that RM has gotten so much more attention over the last half-century and counting compared to MM may attest to sexism--unconscious, of course--in the world of American crime fiction and the powerful psychic hold of the PI novel.

He is hugely important in the genre, of course, but then so is she too. They were a remarkable crime writing couple. Just as it recalls certain early Seventies Agatha Christie titles, The Blue Hammer also recalls, on one key plot point in particular, Margaret's then recent recent crime novel Beyond This Point Are Monsters (1970).

The back of my paperback edition quotes the review from the Daily Telegraph: 'Richly plotted, economically told'. I gather you find the first half of that verdict more accurate than the second?

ReplyDeleteI have not read that many Ross Macdonald novels, but I remember liking some of them and finding others repetitive. Margaret Millar, on the other hand, is one of my favourite crime writers.

It's definitely got an involved plot along classic lines, but the telling is murky. Margaret Millar books are definitely more cleanly plotted, but then so are earlier RM books. The Blue Hammer is more like Sophie Hannah--ugh!

ReplyDeleteLove Marge!

Strange -- I've read all of Ross Macdonald's novels, and I thought THE BLUE HAMMER was one of the very best.

ReplyDeleteWell, tastes differ. Obviously there was a market for the sort of novel RM was writing in the late Sixties and Seventies, those books just don't appeal to me however.

Delete