|

| Not Julian Symons again! |

One thing you know if you've read much Julian Symons mystery criticism: He really liked the work of Dashiell Hammett. He devoted four whole pages to Hammett in the first (1972) edition of his genre survey Bloody Murder, a book which modestly runs to under 270 pages.

Symons liked Raymond Chandler too, though he avowed that "it must be said" that Chandler, lacking Hammett's "toughness," "comes off second best" in comparison with Hammett.

All this has to be said," declared Symons redundantly after surveying Chandler's faults as he saw them--verily, Symons was a great sayer of things that that in his view had to be said--yet he allowed that Chandler "was a very good writer." Fair enough!

What's striking to me, however, is how, Chandler aside, other hard-boiled or noir writers from the Thirties fared so vastly more poorly in comparison with Hammett and, indeed, were treated almost as negligible. William Faulkner, a great writer but a crime fiction dilettante, gets an entire paragraph from Symons, but James M. Cain, W. R. Burnett and Jonathan Latimer are confined to one or two sentences apiece, as is Cornell Hopley-Woolrich, as Symons calls him, while many others go unmentioned. Symons backhandedly credits Woolrich with "plots which dazzle by their ingenuity in the half-light of evening, but when the morning comes seem rather contrived," singling out for mention his novels Phantom Lady and The Bride Wore Black.

At his death in 1968, four years before the first edition of Bloody Murder was published, Cornell Woolrich had become something of a forgotten man, though the great French director Francois Truffaut made films from two of his novels in 1968 and 1969. His now long and steady rehabilitation began with the publication in 1971 of the Woolrich short fiction collection Nightwebs, edited by Francis Nevins, but one does not get the impression that Symons was acquainted with Nevins' anthology when he was drafting the first edition of Bloody Murder.

However, in the final edition of Bloody Murder, published two decades after the first, Symons made clear he had read Nightwebs (or at least parts of it)--though the effect of it had only been to prompt him to become further dismissive of Woolrich. People who are aware of Symons' dismissal of the "Humdrum" British detective novelists and some of Britain's Crime Queens (especially Dorothy L. Sayers) may yet be surprised to see the casual dismissiveness with which Symons writes of Woolrich, his great advocate Francis Nevins and the United States in general:

Cornell George Hopley-Woolrich (1903-1968)...is at present a cult figure in America, "one of the greatest suspense writers in the history of crime fiction," as one enthusiast mistakenly puts it....His best writing is in the novels he produced at great speed in the early forties, especially The Bride Wore Black (1940)…and Phantom Lady (1942), but the melodramatic silliness and sensationalism of many of his plots, and the continuous high-pitched whine of his prose--seen at its worst in the collection of stories Nightwebs (1971)--preclude him from serious consideration.

Doubtlessly all this "had to be said," but while my observation which follows here may not truly have had to be said, just let me say it anyway, borrowing a word from Archie Goodwin, as I recollect (at least the television version of Archie as played by Timothy Hutton): As a critic, Julian Symons can be a poop.

What arrogance on his part! One has to wonder what Nevins--the "enthusiast" to whom he patronizingly refers--did to provoke him. I suppose praising Woolrich's writing so effusively.

God knows I have my criticism of Nevins--mainly centering on his calumnies against Woolrich on a personal level and a general attitude which I deem antigay--but the man did do an incredible amount of work on the author and almost singlehandedly revived his work in the Seventies and Eighties. For that he deserves some respect. Symons could not even bring himself to name Nevins in Bloody Murder. Pah! Pfui!

The only effect of Nevins' work on Symons was to cause the critic to downgrade Woolrich further, damning his work as marred by "melodramatic silliness and sensationalism." His comment about "the continuous high-pitched whine of his prose" is one of the nastiest cracks which Symons makes against another crime writer in Bloody Murder.

Certainly Woolrich is not a strictly "realistic" writer like Hammett supposedly is, but this sweeping dismissiveness seems manifestly unfair on Symons' part. I don't really know how well read Symons was in Woolrich--all we really know, apparently, is that he read The Bride Wore Black, Phantom Lady and Nightwebs--but even a reading of some of the tales in Nightwebs (Did Symons not get past the first section?) shows that there is realistic detail to the stories, including a forthright treatment of police brutality and the economic privation of the Depression.

There is also emotional honesty and intensity, though I suppose this is what Symons dismisses as Woolrich's "high-pitched whine." Certainly Symons is not the first person to criticize purple patches in Woolrich's passionate prose, though those particularly sneering words are unique.

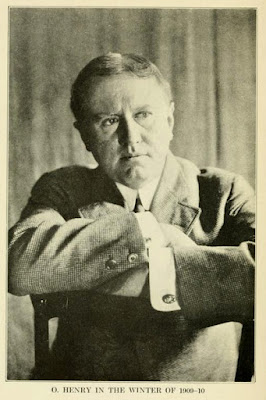

In the end I suppose Symons disliked the emotionalism and artifice of the Woolrich tales, which owe a certain debt not only to Edgar Allan Poe but yet another great American writer, O. Henry. Symons also never thought much of most of the between-the-wars Had-I-But-Known and mid-century domestic suspense writers (mostly women) with whom Woolrich shares an affinity, judging by Bloody Murder, where he deems few of them worthy of inclusion and serious discussion.

Conversely Symons upgraded Burnett and Cain in the last edition of Bloody Murder, crediting them despite limitations with making "considerable contributions to the American revolution in the crime story." It is astonishing to me, however, that Symons could not see the same thing in the case of Woolrich, whose influence on noir in his own work and the many radio and film adaptations made from it seems patently obvious.

Symons seems to have been blinded, not for the first time, by his own strong opinions, which conflict with his job as a genre historian. Personally I don't like the writing of, say, Jim Thompson all that much, frankly, but his influence on the genre obviously was great, whatever I think of his work.

But then Symons is dismissive of Thompson too. He briefly shoehorns Thompson into a discussion of pulp writers from the Thirties, declaring that he was nothing "more than an efficient imitator of other writers in the genre." Thompson, he incredibly concludes, lacks "individuality," making it difficult to tell his work from anyone else's! This would shock Thompson's American fans, though being, I suppose, according to the Symons view, a bunch of naïve American cultists, what would they know? At least Thompson fares better than David Goodis, who gets only two microscopic mentions in the final edition of BM. (Neither is mentioned in the first edition.)

As the years go by, I like Symons less and less as a crime fiction historian, though I do believe his due should be paid to him as a crime writer--he wrote some fine books and even some genre classics--and more generally as a critical essayist. The problem with Symons as genre historian, it has to be said, is that he just could not or would not step back enough from his own personal biases. Bloody Murder needed less of his opinions, in my opinion, and more objective history. There, I've said it.

No comments:

Post a Comment