The consensus on Cornell Woolrich is that in the 1950s his fiction writing went into a steep decline, accelerating after the death in 1957 of his beloved mother, Claire, with whom he had resided at New York City's Hotel Marseilles for the last quarter century. The Thirties and Forties were Woolrich's great decades as a writer, when he produced the short and long fiction that made his name and launched scores of films. There were over 170 (!) crime short stories and novelettes--over 100 of them just in his peak pulp years between 1936 and 1939--as well as eleven novels, including classics like The Bride Wore Black, Phantom Lady, The Black Angel, Deadline at Dawn, Night Has a Thousand Eyes and I Married a Dead Man.

Certainly in the Fifties Woolrich's work production declined precipitously. Often the author mendaciously presented old work as new, albeit after giving it a certain amount of revision. As he himself sank into the torpor of alcoholism, squalor and desolating loneliness, so too did his once astonishing work ethic begin to decay.

In August 1958, about ten months after Claire passed away, Woolrich published a mainstream work of fiction which he had been working on for several years. Entitled Hotel Room, the book was a collection of short stories tied together by the fact that each story is set in the same room, #923, at the fictional Hotel St. Anselm in New York, doubtlessly modeled after Cornell's and Claire's own Hotel Marseilles. The author dedicated the novel to his late mother, calling it "Our Book." An up-to-date photo of a pale and gauntly forbidding Woolrich was included on the back of its dust jacket.

Woolrich's biographer, Francis Nevins, is condescending toward Hotel Room, as only he can be, sneering in his biography:

Woolrich was straining to write significantly....the style is ponderous, laughably overloaded with elephantine metaphors and similes, posturings and preachments....a book that is often positively painful to read.

I don't get Nevins at all here, but then I frequently don't get Nevins on Woolrich, when he puts him down so hard (and occasionally overpraises him). Much of the book is well written, I think, and in any event it's not worse written, in my eyes, than his crime writing, which Nevins professes to adore. Nevins scoffs that "the book wasn't even reviewed in the New York Times," but it was in fact reviewed favorably in many newspapers. Ultimately, I think, the book is not a great success, but it is interesting and successful in pieces, something of a curate's egg, though with more good parts than bad.

Nevins thinks that the brilliant "The Penny-a-Worder" (which Nevins calls--and I agree--Woolrich's best original short story from the Fifties) was cut from the book because the publisher, Random House, wanted all the stories, outside of the framing ones, to be tied in with historical events, If true, as seems likely, it was an unfortunate and indeed rather stupid decision, but there are still several good stories remaining in the volume.

Nevins also cites several other stories that might have been originally intended for inclusion in Hotel Room, including "The Poker-Player's Wife," "The Number's Up" and "The Fault-Finder," the latter of which is non-criminous and was never collected. I hope that it will be someday, though Nevins is dismissive of the tale. Another possible Hotel Room discard was recently rediscovered by Nevins and it was published last year in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine under the title "The Dark Oblivion," impressively netting the author an Edgar nomination, fifty-four years after his death. I have not yet read this story, but I certainly need to do so.

It is worth noting as well that Woolrich's brilliant 1938 mystery story "Mystery in Room 913," aka "The Room with Something Wrong," (reviewed by me here) is set at the St. Anselm too--just a few doors down from the room in Hotel Room. It is a story which graces any crime fiction anthology, but the pure mystery content in it is too high for it to have been included in a mainstream work like Hotel Room.

|

| Hotel Marseilles, New York |

All of the stories in Hotel Room are titled The Night of...., with a specific date attached. The first of them takes place when the hotel opens in 1896. It is one of Woolrich's "Annihilation stories" as analyzed by Nevins, wherein a person seemingly vanishes off the face of the earth, though here the purpose of the vanishing is to not to produce a crime baffler or spine-tingling suspense but rather tragic melodrama.

The vanished person is a young newlywed husband from Indiana, on his honeymoon night at the St. Anselm with his even younger bride. He shyly steps out for a minute to allow her even more shyly to get changed for bed--and we never see him again.

It's a moving tale, achingly evoking the desolation of enforced solitude in a hotel room, something Woolrich himself knew so well; and, if one is so inclined, one also can see in it reflections on Woolrich's own disastrous, extremely short-lived marriage, about which I have written over at Crimereads.

Woolrich's marriage failed, apparently, because he did not desire to, or was unable to, consummate it, leading his frustrated wife to leave him and eventually secure an annulment, after humiliating him nationally in the newspapers, with accounts of how he was a pallid aesthete who adored his wife too much to have sex with her. Woolrich certainly well conveys a couple's nervousness about having sex in the first Hotel Room story. Later on in the story a doctor, speculating on what happened to the husband, avows:

If a boy is brought up in a strict, religious household, and trained to believe all that [sex] is sinful--then his conscience will trouble him about it later on. The more decent the boy, the more his conscience will trouble him....I think this boy ran away because he loved her, not because he didn't love her....

Was this Woolrich's mea culpa on his marriage?

|

| The signing of the Armistice celebrated on November 11, 1918 |

The next two stories, which respectively take place on April 6, 1917, when the U. S. entered the Great War to fight Germany, and November, 11, 1918, when the Armistice was declared, really constitute one story told in two parts. All together it's about a young man and woman who impulsively make a war marriage and ironically come to feel rather differently about the whole thing a year and a half later.

This is a wise and wryly humorous observation of shifting American sexual and generational mores, the sort of thing Woolrich must have written for the romance magazines in the Twenties, though it's more sexually explicit than he could have been in magazines at that earlier time. It does rather remind one of Woolrich's early literary idol, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

For me the snag is in the next two tales, one a violent, nasty crime story taking place in 1924 that really feels out of place here, and the other, taking place on Black Thursday, 1929 at the onset of the Depression, about a man stepping back from committing suicide, that is altogether too falsely peppy. Sad to see "Penny-a-Worder" getting bumped for these two tales!

Woolrich rebounds in the brief penultimate story, which takes place on the eve of Pearl Harbor, which though very short indeed packs quite a punch, at the end. (It's a twist in the tail story.) However, after that we are already at the second half of the framing story, taking place when the hotel closes in 1957, and that's that. The biggest problem with Hotel Room is that it is too short. It definitely could have used the inclusion of "The Penny-a-Worder," not to mention the other excised tales (though I could have done in any case with "The Number's Up," which is almost too cruel and depressing for words.)

One of the striking things about Hotel Room is the sense of human sympathy one senses from the author. Not for the first time, Woolrich is condemnatory as well of nationalism and racial prejudice and I think he has gotten insufficient credit for this as an author in accounts which continually emphasize his many queer hang-ups and phobias. There was a real intelligence in this author and a sense of empathy, although admittedly it often curdled into gloomy, even nihilistic, pessimism.

*******

We certainly see this pessimism in the penultimate collection of short stories published by Woolrich during his lifetime, The Dark Side of Love: Tales of Love and Death (1964), which carries a telling epigraph from the poet Auden: The More They Love/The More They Feel Alone.

Woolrich must have been in a bleak mood indeed when he conceived this slim volume of eight sad and often sexually perverse tales, cheaply produced by back number publisher Walker. The collection received little notice at the time and has a pretty poor reputation, yet in my view it is by no means a negligible book.

"The Clean Fight," which Nevins greatly admires, is a damnably confounding story, and one I personally find extremely repulsive. It's all about how police hunt down and kill a man indirectly responsible for the death of their beloved retired captain's son. (The hunted man was another cop who for a bribe informed on an upcoming police raid.)

The retired police captain, who lives as a gross bedridden alcoholic in a hotel room after suffering a stroke (shades of Woolrich's fate), is an unpleasant character indeed, telling his former men (who bafflingly are still loyal to him to a man):

I want to see him [the informer] lying on the floor, beaten until he can't feel it any more. Then brought back, and beaten some more, and some more, and some more. I want to stamp down on him with my foot myself. I want to spit into his open, speechless mouth.

thwarted hate of the pack when the rabbit has eluded them....and when the pack happens to be the police, unaccustomed to such defiance, this can be a terrible thing. Far better to lose the game than to win it. For it can't be won anyway....one man alone cannot stand against them [the police], no matter how wealthy he is, no matter how adroit or basically non-criminal or legalistically unpunishable.

This does not really sound approving of the police and brutal private avengers, like Spillane, but rather simply resigned to the terrible inevitability of such brutality and its efficacy.

Or was there a masochistic quality in Woolrich himself? Did some part of him like being emotionally hurt, perhaps even literally physically beaten?

Being convinced that Woolrich was gay, Nevins attributed the author's attitude toward the police to a homosexuals' self-contempt (when the police beat up a man in his fiction, you see, Woolrich is figuratively beating up himself for his homosexuality); but perhaps the author simply was a masochist, whether gay, straight or something else yet on the sexual spectrum. Love hurts, as they say, and Woolrich always seemed to make certain that it did in his case.

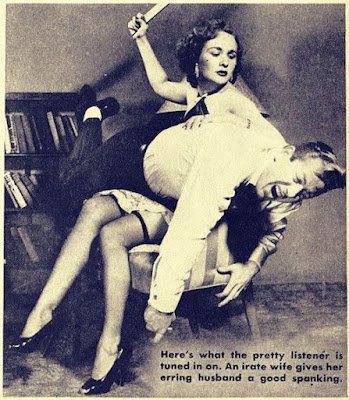

|

| Please, mum, may I have another? |

This reading seems backed up by another tale in the collection, "The Idol with the Clay Bottom," which is about a prostitute with a heart of, well, brass perhaps, who falls in love with a noble, manly protector named Don, only to learn that, as a result of his upbringing with a blowsy, brutal stepmother, he is in fact a masochist, sexually stimulated by spankings.

This story seems to have been uniformly ridiculed, perhaps because people are nervously uncomfortable with the subject matter, but certainly individuals like the man in this story existed and still exist in this real twisted world.

Woolrich attempted to get this queer story, which he termed Rabelaisian, published as early as 1944, according to Nevins, yet he didn't succeed until the Swinging Sixties.

I actually don't find this a bad piece of fiction, though Nevins primly pronounces it a "wretched waste of ink." When in the story frame the prostitute, Marie Cameron, is asked by a nameless client whether she was ever in love, she replies, resignedly, that she was once, adding: "You can't expect to be that lucky: to have it miss you." The Woolrich philosophy in a nutshell: Love to regret it.

To me this gives the last line of the story a frisson not of romance but of disquiet. The story also includes the memorable line, "shrilled" from our hooker heroine to her disturbed beau: "Geddaway from me!....You're queer for paddy whacks!" Try using that one sometime.

Another, more forgettable tale from the collection, "The Poker-Player's Wife," also has a decidedly masochistic edge to it in the way that the titular spouse self-sacrificingly allows her poker-player husband to treat her. "Je t'Aime," about a Parisian love triangle (or perhaps another geometric formation), is a tale of mild, though murderous, irony, which was originally published the previous year in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, this being the only one of these works, apparently, which the fastidious Frederic Dannay would touch. It comes off almost as "normal" compared to most of the rest of the stories in this collection.

The most bizarre of the stories is "Somebody Else's Life," which originally appeared in teleplay form in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1958. It is a sort of temporal soul transference tale that illustrates a spiritual medium's warning to a French gambling addict countess that

The past is the future that lies behind us, the future is the past that lies before us. Only fools think that they can divide the two in the middle.

Adherents of Nevins' notion that a young Woolrich once donned a sailor suit and roamed the docks in LA in search of male sex partners might be struck by the countess' belief that one can truly alter one's life for the better by donning another person's clothes, but of course the woman's desperate hope comes to naught.

Then there's "Too Nice a Day to Die," a tale greatly admired by Nevins, which is an emotional conte cruel--and then some. It's about a girl who by a quirk of fate decides at the last minute not to commit suicide, then meets a nice boy, then....you see the ending coming a mile off, though you hope against hope it won't end that way. This is Woolrich at his gloomiest, remember.

There are two other stories in this collection that especially struck me: "Story to be Whispered," about a man who murders a male-to-female cross-dresser (or transgendered?), which Nevins, naturally, deems indicative of "Woolrich's contempt for himself." What was it, one wonders, when Mickey Spillane had his psychotic detective hero Mike Hammer murder a cross-dresser in one of his novels?

Yet in "Whispered" is the view of the narrator--or more accurately that of the narrator's defense attorney--meant to represent Woolrich's view, as Nevins apparently thinks, or is the tale simply a depiction of a violent crime, the sort of thing which, unfortunately, occurred all too often in real life (and still does)? It isn't so clear to me as it is to Nevins.

Indeed, the more I think about it, I believe the last line of the story is meant to undercut any notion that the murder of a "queer" is something of no moral consequence--which is precisely the opposite of the conclusion which Nevins draws from the story. Rather than self-hatred and self-contempt, the story, as I see it, is indicative of Woolrich's rueful consciousness of the awful panoply of human tragedy.

Then there is "I'm Ashamed," about the visit which two nice, middle-class, underage boys make one adventurous Saturday night to a local whorehouse and the dreadful consequences which it has for one of them. It's an evocative picture of a bygone era and its mores and the agonies and awkwardness of youth, with some of the plotting skill of his crime fiction. It probably tells us something as well of Woolrich's own sexual anxieties and his problematic relationship with his adored but distant Mexican father, who probably called upon more that one bawdy house himself.

According to a cousin, Woolrich as a child threw a great fit after seeing his father, who was estranged from his mother, in bed with another woman. His feeling towards both his parents, both of whom left him alone so often when he was a child, was extremely needy and dependent all through his adulthood.

Very briefly reviewing The Dark Side of Love in a newspaper, esteemed crime writer Dorothy B. Hughes tepidly advised: "For Cornwell Woolrich fans, yes; for others these eight unpleasant stories are unrelieved by anything but gloom." It's a mostly fair enough assessment, but I am a Woolrich fan, especially of his short fiction, and I am glad to have walked for a time on the dark side of love and longing with this grim volume. Both it and Hotel Room have never been reprinted since their original publications; perhaps it's time that these omissions changed.

|

| A. Rothstein, photographer |

.jpg)

I haven't read much late-stage Woolrich (I'm trying to go in some vague semblance of chronological order), but Hotel Room has always intrigued me on a conceptual level. It would certainly be interesting to see a version of the book as Woolrich originally intended it...

ReplyDeleteAs it happens, "The Idol With the Clay Bottom" is one of his few later works I have read, and while I'm struck by how sexually transgressive it is, what perhaps strikes me more is how curiously neutral the tone is—Woolrich, as narrator, seems to very deliberately avoid passing any judgment, and there's a distinct ambiguity to the end that is indeed "disquiet[ing]," as you say. It's frankly no surprise it took him so long to get it published.

On the topic of Woolrich-as-masochist, I have wondered (half-jokingly and half-not), if his "dark secret" wasn't that he was gay, but that he was instead into femdom, pfft. So maybe you're onto something. (At the very least, it's certainly no wilder than the "he was definitely gay and furthermore dressed up in a sailor suit to go cruising" theory.)

Anyway, thanks for another wonderful post! I always enjoy your writings on Woolrich, specifically—they're such a welcome breath of fresh air in an otherwise (irritatingly) Nevins-dominated environment.

Seeing his marriage photo with Gloria, aka Big Bill, I'm reminded me of the Joan Armatrading song "I Love It When You Call Me Names," with its lyrics

DeleteBig woman and a short, short man

And he loves it when she beats his brains out

He's pecked to death but he loves the pain

And he loves it when she calls him names

Honestly, who knows? Bill obviously wasn't quite the saintly virgin Nevins makes her out to be. Both of them had some loose screws, it seems clear to me, but then so do a lot of us. Maybe the person without any loose ones is wound too tight.

I'm revising this piece a bit because as I thought about Story to be Whispered, it became clear to me that the last line makes clear it doesn't support the anti-queer, self-contemptuous reading Nevins draws from it. I think there's a neutrality, as you saw, or a non-judgmentalism to a lot of these stories.

I'm also looking at the one story I didn't talk about from the collection, which is straight on sci-fi or fantasy but has some interest too as I think about it.

Thanks for your comments, it's encouraging that someone who likes CW a great deal also enjoys my posts about him and his writing.

Queer characters obviously don't show up a lot in Woolrich's work (owing to the era), but when they do, I'm struck by how...well...not exactly positively they're portrayed, but at least how, yes, neutrally and even borderline-sympathetically they're portrayed—particularly when compared to other pulp/noir writers of the day. One of my favorite parts of "The Dancing Detective" is when Ginger, the main character (in a blink-and-you'll-miss-it line), is implied to dance with a gay guy, and while there is some stereotyping on her part, there's otherwise no judgment or disgust. It's a curious, subtle detail, and far from the only one of its kind in Woolrich's oeuvre.

DeleteOne of the issues I have with Nevins (and oh, there are so many!) is that he seems to take it for granted that we're supposed to like all of Woolrich's protagonists, and that the author himself personally identified with all of them. Which...I don't think was always the case? But then, I never got the impression that Nevins was a particularly adept analyst to begin with, so color me unsurprised on this point.

You're very welcome—and I enjoyed the additions/revisions!

Yes, one has to be very careful doing that when one is doing biography of an author. And then Symons takes as fact (which it isn't isn't) that Woolrich was gay and attributes to that his "self-contempt" (which I do think he suffered from). When it's quite possible that Woolrich may have felt self-contempt due to other issues, like body image issues, for example.

DeleteWoolrich reminds me of the 98-pound weakling in the Charles Atlas bodybuilding ads. A part of him may have envied the manly, tough cops in his fiction, who take charge of situation and their women, even as he recognized they went over the line, again and again. A part of him may have wanted to be those men, rather than have sex with those men.

This is where we may have to agree to disagree, because I'll admit I see more of a critique/commentary on contemporary ideals of masculinity in Woolrich's work—particularly as they relate to women and gender politics—than I see some sort of self-insertion wish-fulfilment fantasy (though there may indeed be some of that, I'll grant you). But in my experience, even his more "macho" heroes tend to have a sensitivity or compassion about them, such that (as a heterosexual woman) they're personally attractive to me in a way a lot of other noir/detective heroes aren't.

DeleteWell, I'm thinking of what Nevins calls his tough "noir cops," who runs the gamut but some are truly repulsive. Like In nightmare, where the cop character really pushes the weak, neurotic protagonist (his brother?) around, unnecessarily it seems to me.

DeleteOften though I think they are often more nuanced than Nevins makes out. I would make that case even for Endicott's Girl and the good cop in Detective William Brown. There's really a lot about cops in his work, it's a whole fascinating subject in and of itself. Some of his cops are sympathetic, those tend to be in the stories Nevins doesn't like, lol.

"Nightmare" is in the queue, but I haven't read it yet, so I'll have to get back to you on that, but I agree that there really is a whole range of "good" cops and "bad" cops in his work. And a lot of cops in general, as you point out—but then, he was writing for a lot of detective pulps, and cops were popular/expected in those. In many instances (especially in the '30s), I think he was simply writing to his audience.

DeleteHis police brutality seems exceptional but one would have to have a deeper read in the pulps than I have to state definitively. I should ask Bill Pronzini!

DeleteIt's worth noting too that Woolrich's cops are still behaving that wat in The Clean Kill in the early Sixties. I'm thinking too of the cop in Dead on Her Feet, for example, ugh! But its certainly a question: how much is personal, how much is writing for your public and publishers, how much simply showing things as they were.

DeleteOh, yes, that's definitely in keeping with the Dark Side of Love stories and could have been included in an expanded collection (probably what they should have done). Ethan Frome with a dash of The Postman Always Rings Twice, plus the Marquis de Sade, but all in modern idiom. Makes you wonder what Woolrich would have written had he somehow gotten himself together and lived until 1983, say, when he was would have been eighty years old.

ReplyDeleteHotel Room has been republished in e-book form https://www.amazon.com/Hotel-room-Cornell-Woolrich/dp/B0007E86I2. I agree with you that it's underrated. I liked it better than 'Mystery in 913' which I thought was less Woolrichian and more generic. Also agree that Penny-A-Worder totally should've been included--perhaps as an epilogue to the novel. It accentuates the ghostly, phantasmic quality to the work. The absence of a trace of the prior stories that occurred in the Hotel Room. In any hotel room, for that matter. I'd love it if someone would collect all of the St. Anselm Hotel stories into a single volume. It's nearly reminiscent of the Beatles mansion in Yellow Submarine where every time you open a door you're bound for a new and strange adventure.

ReplyDeleteIt's a very intriguing idea for a book, and perfectly suited for Woolrich, who loved out life in hotel rooms. Much underrated by Nevins.

Delete