This comeback film for the two talented yuksters spurred a whole new series of Abbott and Costello films, wherein the pair "met," for example, the Killer, Boris Karloff (1949), the Invisible Man (1951), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1953) and the Mummy (1955) Some of these films incorporate mystery elements as well.

But Abbott and Costello's filmography goes back farther than that. They first appeared together on film as a comedy team in One Night in the Tropics in 1940, stealing the show. The next year they starred in the smash hit Buck Privates, which was followed over the next couple of years by In the Navy (1941), Hold That Ghost (1941), Keep 'Em Flying (1941), Ride 'Em Cowboy (1942), Rio Rita (1942), Pardon My Sarong (1942) and Who Done It? (1942). Two of those titles will immediately suggest themselves to mystery fans: Hold That Ghost and Who Done It?

|

| a dark and stormy matte painting |

Hold That Ghost is an old dark house flick played for laughs, like Bob Hope's The Cat and the Canary (1939) and The Ghost Breakers (1940), films which set the gold standard for this sub-genre. In the film Abbott and Costello are gas station attendants who manage to inherit a deceased gangster's old Twenties-era roadhouse. (Don't ask me to explain how this comes about here, but the gangster's will reading scene is amusing.)

They go out there, one dark and stormy night, and it turns out that the moribund roadhouse is quite the old dark house. Let me add in passing here that these early Abbott and Costello flicks really had great set designs: the old dark house in this film is a splendid one indeed, riddled with secret passages and hidden rooms, and it's just all-round cobwebby creepy.

|

| Don't they know to stay out of the cellar? Bud Abbott, Lou Costello, Richard Carlson |

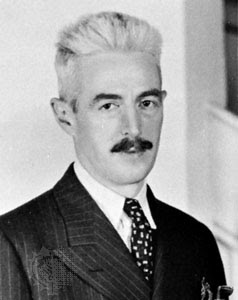

Other people end up at the defunct roadhouse as well: pencil-thin mustached gangster Charlie Smith (Marc Lawrence), obviously up to no good; a beautiful blonde, Norma Lind (Universal's "Scream Queen" Evelyn Ankers); handsome, bespectacled Dr. Jackson (Richard Carlson), who seemingly has eyes more for water microbes than for lovely Norma Lind; and wacky radio mystery star Camilla Brewster (Joan Davis).

Another thing I have to interject here is what a good supporting cast this is! Abbott and Costello films followed a pattern, common for the day, of having a romantic subplot run parallel with the zany doings of our boys. Often in these situations the male and female lovers are bland and boring, making their passages d'amore a chore to watch, but here the dependable Evelyn Ankers and Richard Carlson are a charming pair.

Carlson in fact had appeared in The Ghost Beakers the year before and in 1941 he was in the acclaimed film The Little Foxes as well. He's best known for King Solomon's Mines, I think, as well as the sci-fi/horror films he did in the 1950s, such as The Magnetic Monster, It Came from Outer Space, The Maze, Riders to the Stars and Creature from the Black Lagoon (another absolute favorite of mine as a kid). He was also in The Spiritualist/The Amazing Mr. X (1948), a fine little film that I reviewed here.

|

| And fangs! Like this!! Bud Abbott, Joan David, Richard Carlson (Evelyn Ankers peeking out from the shadows) |

Then there's Joan Davis--best known today, I believe for the Fifties television series I Married Joan--who is superb as the comic female in the film. She adds a lot from the humor standpoint, including a memorable waltz-rumba dance scene with Lou Costello.

And let's not forget Marc Lawrence, whose credited film career spanned seventy years, from White Woman (1933), not at all a bad thriller with Charles Laughton and Carole Lombard (reviewed by me here) to The Shipping News (2001) and Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003) Lawrence appeared in countless crime shows on the big and small screens over the decades, often playing gangsters. He had good roles in such classic films as This Gun for Hire, Key Largo and The Asphalt Jungle.

|

| Hail, Hail, the gang's all here (and a certain person is totally stressed out again) Bud Abbott, Lou Costello, Evelyn Ankers, Joan Davis, Richard Carlson |

I should also mention Shemp Howard, who has one nice scene in a drugstore, and Mischa Auer, who appears in book ending nightclub scenes, which also include numbers by the Andrew Sisters and Ted Lewis, performing his theme song, "Me and My Shadow" (a performance that you would not see today).

In only their third of many starring outings, Abbott and Costello are in top form here, Abbott bossy and bullying (at times he comes off like a snarling Dan Duryea) and Costello the not-too-bright man-child, who gets very stressed out indeed in trying situations.

He has one of his classic bits here, involving a pair of candlesticks. I also love the discussion he, Abbott and Joan Davis have about "figures of speech," it's a hoot. I know some people consider Abbott and Costello's humor unpardonably low, but I admire the gusto Costello put into his best performances. In his own way I think he was a comedy genius.

Hold that Ghost is, I think quite a bit better than Who Done It? Abbott and Costello don't seem as funny here, and the supporting cast, which includes some fine players, like Thomas Gomez (the murder victim), William Bendix (dumb cop) and Mary Wickes (gal Friday, essentially the Joan Davis role from Ghost), don't have as good material either.

Patric Knowles and Louise Allbritton carry the romantic subplot here and while they are perfectly competent and pretty to look at, they come off as rather aloof and superior and don't have the sparks that the more naturalistic Ankers and Carlson do in Ghost.

Still, there are some good bits, including a great finale (I can see the influence on the 1994 film Radioland Murders, reviewed here), and there's a wonderful evocation of a radio mystery series, Murder at Midnight, in a couple of scenes. I don't know who played the radio announcer, but he did a fine job in this part.

"Murder! At Midnight"....(cue woman's scream)