|

| 1940 Simon & Schuster first ed. |

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

Who cry'd "La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!"

--La Belle Dame sans Merci (1819/20), John Keats

Just over four score and a single year ago, in December 1940, Simon & Schuster published Cornell Woolrich's debut crime novel, The Bride Wore Black.

After publishing, with decreasing success, six mainstream novels in the six years from 1926 to 1932, before he was even thirty years old, Woolrich, seemingly a washed up mainstream author who had been nationally humiliated by his soon-to-be ex-wife (see my upcoming article on Woolrich), turned to writing fiction for the crime pulps in 1934. Only 14 Woolrich crime stories appeared in 1934-35, but then the creative explosion occurred.

In 1936 there were 26 stories, in 1937 there were 36, in 1938 there were 20 and in 1939 there were 21 (including the four part The Eye of Doom, which two decades later Woolrich revised as a paperback original called The Doom Stone). With the earlier ones, this made nearly 120 crime stories published in six years--an impressive output indeed.

By 1940, however, Woolrich was ready to break out of the box of pulp fiction and get back into publishing novels again. These were crime novels, to be sure, but crime novels with a difference. Shifting the emphasis from the solving of the mystery to that of the horrific travails undergone by people impacted by crime, Woolrich became one of the instrumental figures in creating mid-century suspense and (and its darkest) noir fiction. The eleven novels he published in the Forties--six under his own name, four as William Irish and one as George Hopley--all are generally considered classics of suspense./noir, although naturally people have their own particular favorites among them.

It's an unoriginal choice, but mt favorite remains Woolrich's first-born crime novel, The Bride Wore Black. It's one of the finest crime novels I've ever read.

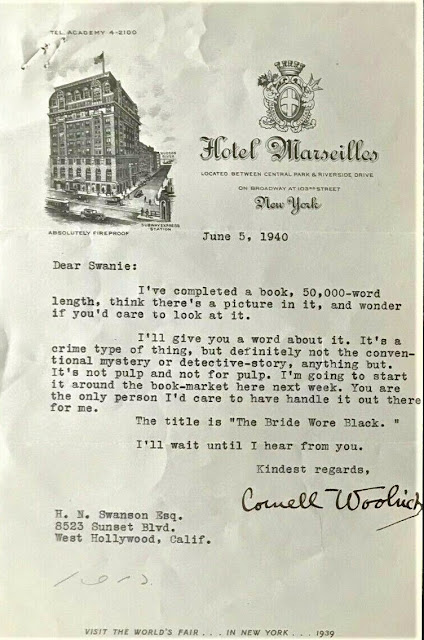

I think Woolrich himself knew he really had something with this one. On June 5, 1940 he sent a letter to Hollywood literary agent Harold Norling Swanson, who as editor of the magazine College Humor had accepted Woolrich's first published short story back in 1926. The letter read as follows:

Dear Swanie:

I've completed a book, 50,000-word length, think there's a picture in it, and wonder if you'd care to look at it.

I'll give you a word about it. It's a crime type of thing, but definitely not the conventional mystery or detective-story, anything but. It's not pulp and not for pulp. I'm going to start it around the book market here next week. You are the only person out there I'd care to have handle it for me.

The title is "The Bride Wore Black."

I'll wait until I hear from you.

Kindest regards,

Cornell Woolrich

"Swanie" was good at getting film studios to buy rights to books; he sold the rights, during a career spanning sixty years, to The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Big Sleep, Old Yeller, Butterfield 8 and The Mosquito Coast. That last novel was published nearly fifty years after the first one!

However, Swanson didn't sell the rights to The Bride Wore Black. Five months later on September 11, Woolrich wrote the agent again on the subject:

Dear Swanie:

I'm afraid it looks like there's no chance for The Bride Wore Black or I would have heard from you by now.

Could you get the copy you have back to me? I think I'll be able to serialize it.

Thanks for trying, and maybe we'll have better luck next time.

Best regards,

Cornell

At the top of the letter Swanson wrote to his secretary, "Tell me where it's been," to which she responded on the letter that the novel had been rejected by Paramount, Fox, Columbia and RKO and was now at Warner Brothers (who turned it down as well).

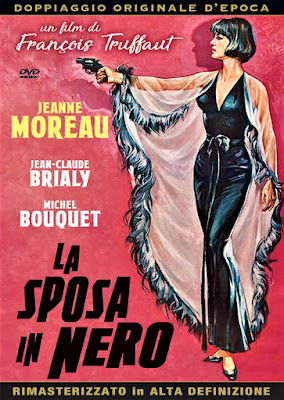

Perhaps Bride was too problematic for Hollywood filmmakers of the Forties, with its deadly, young, beautiful female serious killer. Films were made during that decade, beginning in 1942, from Woolrich's novels The Black Curtain, Black Alibi, The Black Angel, The Black Path of Fear, Phantom Lady, Deadline at Dawn and Night Has a Thousand Eyes, while I Married a Dead Man was filmed in 1950.

Not until 1968 was a film made of The Bride Wore Black, however, this the famous version by French film director Francois Truffaut. Woolrich was invited to the New York premiere (which is more than Alfred Hitchcock bothered to do when he made his film Rear Window from a Woolrich story), but, sadly, the author, in poor health and generally deflated and demoralized, declined the invitation and never saw the film. He died from a massive stroke a few months later.

How much more hopeful things must have seemed for Woolrich in 1940! When Simon & Schuster editor Lee Wright got a glimpse at his manuscript she was immediately wowed by it. As she explained in a 1979 interview:

I read it very quickly--I always read books very quickly--and called him at once and said it was magnificent....

[Woolrich] was just in a state of euphoria. I never could convince him that anybody who read that book would have taken it. You know, these books come along occasionally that anybody would buy who was an editor, or that person shouldn't be an editor. It was like Ira Levin's A Kiss Before Dying. You know, I was the first person who saw that [Kiss Before Dying]. It [Bride Wore Black]was a great good book.

Wright explained that Woolrich was a decidedly neurotic client, on the one hand declaiming that his work was no good, on the other hand, resenting any criticism of it. (I don't believe this paradoxical stance is an unknown phenomenon in authors, but apparently, if you believe Wright, it was more advanced in Cornell.)

"I think he had an absolutely unmixed double reaction to his work," Wright recalled. "One was that every word he wrote was marvelous, magnificent, and shouldn't be changed. And the other was that everything he wrote was terrible, awful, and nobody should read it."

Simon & Schuster would publish Woolrich's first three crime novels, but, according to Wright, after she suggested that he make changes to a single paragraph in his manuscript of Phantom Lady, he balked. "Well, that was the last I saw of him and the last I saw of the book," Wright recalled. "He took it right around the corner to somebody else." Woolrich, incidentally, tells another story, entirely different, about his departure from Lee Wright and S&S, so perhaps not everything Wright says concerning Woolrich should be taken as gospel.

Phantom Lady was published under Woolrich's "William Irish" pen name, by Lippincott, while the next novel which appeared under his own name, The Black Angel, was taken by Doubleday, Doran's Crime Club imprint. Whatever the reason Woolrich left Simon & Schuster, maybe on the whole it was a relief to Wright, because she did not like working with Woolrich and she did not like him; but certainly she and the crime writer had put out a great book with The Bride Wore Black.

The published version of the novel is about 60,000 words, rather than the 50,000 Woolrich named in his letter, but it's still a short book at that length too.

With the exception of the last one, Rendezvous in Black, all of the "Black" novels which Woolrich published under his own name are much tighter than his William Irish and George Hopley books, which I feel works to their advantage. Not everyone agrees with me, however. (See below.)

Compared to works like Waltz into Darkness or Night Has a Thousand Eyes, Bride has the spareness and elegant construction of a play (which leads me to wonder why Woolrich never wrote one). It's divided into five relatively equal parts (though part 3 is about twice as long as parts 1 and 2 respectively), with each of these parts opening with a short chapter entitled "The Woman."

Who is the woman? We just learn that she's young and lovely and that her name is Julie. when the book opens, a girlfriend is seeing her off at Grand Central Station, where she buys a one-way ticket ticket to Chicago. However, once her friend has left the station, Julie takes a taxi and gets a room in town at a boarding house. She takes certain odd actions in her room, burning a photograph of a young man and five strips of paper, then she moves over to the window and looks out at the vista:

She seemed to lean toward the city visible outside, like something imminent, about to happen to it.

And indeed something is about to happen to city, or, rather, to five men in the city, the men whom Julie embarks upon slaughtering one by one.

|

| neon noir 1984 Ballantine edition |

The Bride Wore Black is surely one of the epochal suspense novels of the twentieth century. There is a mystery in what is motivating Julie, but the impetus of the narrative is sheer suspense: Will Julie accomplish her plan, and how will she go about it?

Each section of the book is focused on Julie's attempt to kill one of the men on her list, as the police ineffectively investigate. Only the last section breaks the pattern, with a flashback and the final revelation of Julie's own fate. Only then do we realize--or most of us anyway--just how intricately constructed the book is. That cleverness in construction is something that should appeal strongly to fans of classic mystery, where plot is elevated in importance.

In that sense we can see Bride's origin in the Golden Age of detective fiction, when plotting was supreme, but the novel is also very forward looking in its suspense narrative. Writers like Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart had heightened suspense in their mysteries, taking emphasis away from pure detection and placing it on the depiction and inducement of emotional anxiety, yet there was always a murder to be solved and a killer to be revealed, often somewhat cumbrously.

Among his Thirties/early Forties contemporaries Woolrich actually reminds me of underappreciated women crime writers Ethel Lina White, Elisabeth Sanxay Holding, Marie Belloc Lowndes and Joseph Shearing (aka Marjorie Bowen) more than any other crime writers I can think of at the moment. (One might mention Francis Iles as well, although his tone is predominantly sardonic, as well as Agatha Christie's wicked short suspense tales like "The Red Signal" and "Accident.")

There is also a lot of similarity with American "domestic suspense" crime writing of the 1950s, except that Bride is a very much darker book than most of the ones produced by that school. In Bride it really does seem like we are witnessing the birth of existentially gloomy "noir" crime fiction. After all, noir is French for "black." Woolrich definitely resembles both French crime writer Georges Simenon in his non-series works and late Forties/Fifties American crime writers Patricia Highsmith, David Goodis and Jim Thompson, all of whom are strongly associated with noir.

Bride immediately made a strong impression on American reviewers. (On the other hand, Woolrich seems to have left little mark in Britain.) They sensed that here was something different indeed from both the traditional body-in-the-library school and the newer hard-boiled school of hard knocks. A reviewer for the Pittsburgh Press likened Bride, with its "breathless suspense," unto film impresario Alfred Hitchcock, if one could imagine Hitchcock "writing a novel the same way he directs a movie."

The reviewer for the Hartford Courant asserted that Bride "departs from all the usual formulae of detective fiction," introducing its beautiful killer on the first page, before similarly concluding that the novel holds you "well-nigh breathless with suspense."

The suspense really is terrific. Each section has superb sequences, though my top choice here would be for the middle one, section three, where Julie is determining how she will murder her latest would-be victim, Moran, who you really don't want to see killed. The last section is almost like one of those British drawing room murder plays, it's that tricky and darkly droll.

Cornell Woolrich's biographer, Francis Nevins, believes that Bride, despite its having long been deemed by many Woolrich's best novel, is actually nothing of the sort. Nevins believes it is underwritten and emotionally unaffecting in terms of its characters, accusations often leveled against traditional detective fiction.

Of course I love traditional detective fiction, so what Nevins sees as weaknesses I see as strengths. I think there are plenty of well-depicted characters and good writing in the story, as well as clarity and celerity. At this time Woolrich still wrote with superb economy, something he had to learn to do in the pulps.

In his later William Irish and George Hopley novels (and in the Woolrich Rendezvous in Black), when Lee Wright was gone and the author seemingly could do entirely as he pleased, there's a verbal sprawl that attenuates my interest. The Irish novel Waltz into Darkness is twice as long as Bride, about 120,000 words (really long for a crime novel back then), with about half the plot as Bride. Twice the novel and half the plot! By the time you are halfway through it, hardly anything has happened. Sure, there's some very good writing (Woolrich gets panned a lot for bad writing, but there's a lot of good writing too), but I feel like Bride offers a better investment of reading time.

|

| 2021 Mysterious Press ed. Huzzah! |

There's not nearly as much descriptive writing in Bride, to be sure, but there is, as I've said good writing, like these lines, with their neat turns of phrase:

They nodded slightly to Bliss in passing, and he nodded slightly back to them, with all the awful frigidity of metropolitan neighbors.

They talked it over a few minutes longer, man to man, with the typical freemasonry of two-thirty in the morning.

As I've said, I felt for the characters, with the possible exception of the arty types in part four, this Bohemian milieu being the most synthetic one in the book. (Bohemians gets it in the neck--and elsewhere--yet again in GA mystery!)

Woolrich writes a lot more about Louis Durand, say, in Waltz into Darkness, but for all the extra verbiage, is he really a deeper character than Bliss or Mitchell or Moran or the Bride herself in Bride? I don't see it, I don't feel it. And rarely did Woolrich achieve a more poignant ending in his novels than he did in Bride, with its chilling final line.

So hats and veils off to to the elegantly devastating The Bride Wore Black, one of mystery novels that you have to read.

This "Mysteries You Have to Read" was supposed to be a series here at The Passing Tramp, but I did the first one a year-and-a-half ago! Hope to do better this year.

Thanks for this look at Cornell Woolrich and The Bride Wore Black. I came across your blog via your Woolrich article on CrimeReads, where you convincingly made the case against the prevailing view of Woolrich as a self-loathing closeted gay man.

ReplyDeleteI left a longer comment on CrimeReads, but it disappeared there. I've been researching the film adaptations of Woolrich's work, and found Nevins' biography a useful reference but found his suppositions about Woolrich's character simplistic.

I find Wright's view that Woolrich both loved and hated his writing consistent with a man who had high hopes in his youth for literary fame that were dashed by society's changing tastes. I wonder if at some level he though he was "too good" for pulp and suspense writing, as he was (in his mind) meant to be the next Fitzgerald.

Oh, I would have loved to have read your comment at Crimereads, that's too bad.

DeleteAs had been said Nevins' book is bibliographically useful. Her has everything in there.

Yes, I agree with you, I think he must have had some sense that he was slumming in crime fiction. He seems never to have convinced himself, like Chandler and Hammett, that he was elevating it, even though the novels obviously were an attempt at that, in some cases successful. Heck, I think the stories elevated it as well.

My CrimeReads post was "marked as spam" for inexplicable reasons. I requested review from Disqus but I have no idea how many years that may take. I'm also trying to wrap my head around Woolrich's relationship with his mother -- your idea that he may have suffered from an undiagnosed medical condition makes their relationship seem a tad less... prurient.

DeleteI tracked down her brief obituary and found it fascinating. I'm almost certain it was written by Cornell.

I bet it was!

DeleteYou just read so much about Woolrich being pale, puny, delicate etc. Why did it never occur to Nevins that there might have been an actual medical issue? He treats everything, so judgmentally, as mere moral weakness on Woolrich's part. I have a a nephew with a gluten allergy and believe me it's grave and it impacts your life in all kinds of negative ways and can even affect the mind. And then CW's upbringing, when he was so obviously emotionally deprived as a child. I feel tremendously sorry for him.

Claire Woolrich's obituary, printed in the Oct. 8, 1957 edition of the New York Times, reads in full:

ReplyDelete"WOOLRICH -- Claire Attalie, on Oct. 6, 1957, beloved wife of the late Genaro, mother of Cornell. Service at Walter B. Cooke Funeral Home, 117 West 72d St., Wednesday, 1 P. M. Interment Ferncliff Mausoleum."

Cornell's father Genaro had not been a part of Claire's or Cornell's life for three decades, and had most likely remarried and fathered a child by his new wife. It's as if both Claire and Cornell maintained a fiction that Genaro had just stepped out for a moment, or was on a brief business trip and would be returning at any moment.

It's also notable that no mention was made of Claire's surviving sister Estelle. The inclusion of Genaro and omission of Estelle leads me to suspect the obit was written by Cornell. Who else would have?

I imagine so. Claire didn't want to live in Mexico and Genaro didn't want to live in New York, you do wonder why she and her son just couldn't accept that it was over.

ReplyDeleteI think though if you look at both families there was a lot of dysfunction. The younger of Claire's two brothers was very disliked by his wife and their adopted son, I learned from the descendants. He was considered quite mentally abusive. Another truly weird thing about Cornell is how he writes so many of his mother's family out of his story, so that it becomes just himself, his mother, grandfather and this wallflower aunt, when in truth there was a multitude of people in that house.

Do we know anything about why Cornell, in adolescence, moved back to New York? Nevins mentions the transition, "his painful life below the border with his father came to an end and his life as a New Yorker with his mother... began", but I can't find any reference in Nevins' biography or in Blues of a Lifetime to the *why*. Have you uncovered anything in your research that sheds light on this?

ReplyDeleteI think he wanted to go back, he just thought his father would come back too. I found he attended one of his aunt's weddings during that period, so he actually had maintained contact with his mother, family members traveled back and forth between New York and Mexico City. Given how possessive his mother was later in life I am surprised she let him stay there so long. Usually in such cases the child goes with the mother and Genaro seemed like a neglectful father anyway. Claire may have been one of those mothers who is more interested in an adult son than a youngster.

Delete