In my end is my beginning....And to make an end is to make a beginning. The end is where we start from.--TS Eliot, Four Quartets

|

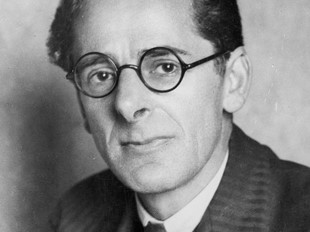

| Jefferson Farjeon (1883-1952) |

So after this blog's near dozen years of existence (it started in November 2011, when I was a mere lad in my forties), I come back to the beginning, to Golden Age English thriller and mystery writer Joseph Jefferson Farjeon. What a time Farjeon and I have had over this period--but more so Farjeon.

Three years after I posted about the author's Christmas crime thriller, Mystery in White, on the day after Christmas 2011, the novel was reprinted as a Christmas release in 2014 by the British Library, who up until that time had enjoyed far lesser success with its reprinting of three forgotten--and decidedly mediocre--detective stories by M. Doriel Hay, a Golden Age back number if ever there were one. (To be sure, a couple of reprints of John Bude mysteries got more favorable attention.)

But things went differently with Jefferson Farjeon's Christmas number, which became a bestseller in England, with 60,000 thousand books sold there by December 21, 2014. In truth Jefferson Farjeon really launched the large scale Golden Age publishing revival, which had been going on but fitfully until Mystery in White appeared.

My book Masters of the Humdrum Mystery, about a trio of Golden Age "Humdrum" greats, John Street (John Rhode/Miles Burton), Freeman Wills Crofts and JJ Connington, had been published in 2012, followed by other books and articles on Golden Age mystery (and many, many blog posts), but it was really Martin Edwards' popular book about the Detection Club, The Golden Age of Murder, published by HarperCollins in 2015, that got widescale attention. Martin occupied his strategic perch with the British Library and the BL since has produced a succession of successful Golden Age revival reprints. Fortunately I have been able to work with other, for the most part, smaller publishers and through them do a lot of things, bringing many authors back into light.

BL published several more titles by Jefferson Farjeon (and John Bude), but regrettably these authors seem to have been dropped by them of late. By Farjeon there was Thirteen Guests, Seven Dead, The "Z" Murders, I know--I can't recall if they did any others. Nobody at BL ever consulted me about it, though I can't imagine that my blog post on Mystery in White didn't inspire the reprinting of the book. When I started blogging about Jefferson Farjeon back in Nov. and Dec. of 2011 there were literally no other posts about Jefferson Farjeon on the internet. I checked. I never talked to anyone who knew who he was, though booksellers then had plenty of copies of his books to sell.

Those have mostly since disappeared, but I was able to get copies of all of his mysteries, and actually read them. With my parents in Louisiana, where I had gone to graduate school, I went to visit Rip Van Winkle, the fanciful Cajun country home of Farjeon's once- famed actor grandfather, Joe Jefferson, for whom he was named. I tried to get in touch with his daughter and nieces and nephews, then still living.

I always felt that Farjeon was one of my finds and was rather proprietorial about him. To have my role in his fantastic, improbable revival go unacknowledged by the people who had been involved in it (one of whom is a great advocate of authors' rights) was a great disappointment, to say the least. But so it goes. Some authors grab the brass ring, others slip and fall and hope they don't break any bones because they may not have the health insurance to pau for mending. I had to move and on and do the best I could.

Jefferson Farjeon, who like his author father Benjamin Farjeon, a contemporary and friend of Charles Dickens, had great sympathy for the little guy, the underdog, like his series tramp character Ben, would have appreciated this situation, I'm sure. When Jefferson Farjeon died at the age of 72 in 1955, he left an estate of just a smidgen over 2000 pounds--about $68,000 dollars today. He came to writing crime novels late, when he was forty years of age, but between his first, The Master Criminal, in 1924 and and his last, Castle of Fear, in 1954, he published 53 of them, or about five every three years. Let me pause to list them here:

1. The Master Criminal 1924 Dial

2. Uninvited Guests 1925 Dial

3. No. 17 1926 Dial

4. At the Green Dragon 1926 Dial

5. The Crook's Shadow 1927 Dial

6. The House of Disappearance 1928 Dial

7. Shadows by the Sea 1928 Dial

8. Underground 1929 Dial

9. The 5.18 Mystery 1929 Dial

10. The Person Called Z 1930 Dial

11. The Mystery on the Moor 1930 Dial (The Appointed Date)

12. The House Opposite 1931

13. The Murderer's Trail 1931

14. The "Z" Murders 1932

15. Trunk Call 1932 Dial

16. Ben Sees It Through 1932

17. The Mystery of the Creek 1933 Dial

18. Dead Man's Heath 1933 Dodd, Mead

19. Old Man Mystery 1933

20. Fancy Dress Ball 1934 Bobbs-Merrill, 1939

21. The Windmill Mystery 1934

22. Sinister Inn 1934

23. Little God Ben 1935

24. Holiday Express 1935

25. Detective Ben 1936

26. Dangerous Beauty 1936

27. Holiday at Half-Mast 1937

28. Mystery in White 1937 Bobbs-Merrill

29. Dark Lady 1938

30. End of an Author 1938 Bobbs-Merrill (Death in the Inkwell)

31. Seven Dead 1939 Bobbs-Merrill

33. Exit John Horton 1939 Bobbs-Merill (Friday the 13th)

33. Aunt Sunday Sees It Through 1940 Bobbs-Merrill

34. Room Number Six 1941

35. The Third Victim 1941

36. The Judge Sums Up 1942 Bobbs-Merrill

37. Murder at a Police Station (as Anthony Swift) 1943 Bobbs-Merrill

38. The House of Shadows 1943

39. November 5 at Kersea (as AS) 1944

40. Greenmask 1944 Bobbs-Merrill

41. Interrupted Honeymoon (as AS) 1945

42. Black Castle 1945

43. The Oval Table 1946

44. Peril in the Pyrenees 1946

45. Prelude to Crime 1948

46. The Shadow of Thirteen 1949

47. The Disappearances of Uncle David 1949

48. Cause Unknown 1950

49. The House over the Tunnel 1951

50. Ben on the Job 1952

51. Number Nineteen 1952

52. The Double Crime 1953

53. Castle of Fear 1954

Farjeon wrote screenplays too, and some of his books were adapted as films, most famously his first Ben the Tramp book, No. 17, in 1932, in a film helmed by on the rise director Alfred Hitchcock. Where did all the money go? Or did not as much come in as we may think?

One problem for Farjeon was that his publishing in the huge American market was erratic. His first eleven crime novels were published in the US by Dial, plus a couple of later ones, before Dial dropped him. Dodd, Mead published one. Then another nine of his were picked up by Bobbs-Merrill, beginning with Mystery in White in 1937 and ending with Greenmask in 1944. But that would be only 23 of his 54 mysteries, about forty percent of his total output.

Perhaps Farjeon's thrillers were too mild for the American market. The critics quite liked him though, on both sides of the pond. The believed retired Yale English literature professor and influential public intellectual William Lyon Phelps was a great booster of his. He died in 1943, a year before America gave Farjeon the boot. Mickey Spillane would come along just a few years later with his crude and nasty hymns to violence. Farjeon must have seemed terrible antiquated.

Jefferson Farjeon was what you might call a kind, gentler thriller writer, not only in comparison with the hard-boiled pulp writers of America like Spillane but even to other British thriller writers like Sapper and Sax Rohmer and Peter Cheyney. The classic Farjeon thriller is about anticipation, with a good dollop of whimsical humor along the way. You might compare it to some of the lighter Thirties film thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock. (Farjeon also wrote light, noncriminous novels of humor and romance.)

Let's now take a short look at Trunk Call, a 1932 Farjeon mystery, his sixteenth, one by no means remarkable in his output, but certainly representative of it in many ways. In this one the mystery novelist Tony Everard has just finished writing his latest book and now is heading out to Torquay for a spot of seaside rest and relaxation. Little does he know what lies in store for him!

Farjeon's writing here is amusing and no doubt wryly autobiographical. As Tony passes the railway bookstall, he notices regretfully that it is "bristling with P. G. Wodehouse, Ian Hay and Edgar Wallace," but that it "did not seem to have heard of T. Everard." Well, that's Farjeon, a humor writer not as popular as Wodehouse, a thriller writer not as popular as Wallace.

Anyway at the Torquay hotel Tony happens to be by the phone booth when he hears a man in there asking for his London number. When the connection is made, the man gets an answer to his trunk call, from Tony's ostensibly empty house! Who in the world could this be? Unfortunately, Tony loses track of the phone caller, distracted by that pretty girl from the train, who has turned up at the hotel too. It seems that pretty girl keeps turning up around him....

Farjeon always knew how to open a thriller, but sometimes the endings don't live up to the splendid openings, and this is one of times. By the second half or so of the novel I was more interested in it for Farjeon's philosophical musings, often rather pithily phrased, like:

Queer ideas come to you at 3 A.M., and you do not refer to them at the breakfast table next morning.

Life is a tussle between joy and sorrow, gloom and happiness, and while we experience the one, the other becomes just a theory.

...he regarded himself in the mirror--and like all palin people he did this frequently in the hope of one day encountering a miracle....[this about Tony's friend Claude; I suspect this is somewhat autobiographical too, though I rather like Farjeon's face]

The best thing on the journey--apart from the actual end of it--was a cup of tea.

Everything is how you look at it. In your happiest moment you may form a sad memory to a stranger with a load on his back. You funeral may be merely a point on the way to a cricket match.

Holiday-makers, revelling in the late summer's attempt to make good its early omissions....

The only reason Mr. Waverley's eyebrows did not continue to rise was because they had now reached the limits of their elevation.

Even in emotional moments, only the greatest writers writers can escape from the lure of alliteration.

How wonderful even terror is...if one goes through it with companionship! I expect that's all life amounts to, really. Loneliness is the only real terror in it!

Near the very end of the novel Tony and that pretty girl, who goes by the Christian name of Elizabeth, discuss the nature of badness--or rotterdom, shall we call it?--and Tony once again waxes philosophical:

We're all Jekylls and Hydes, you know. The quantities of Jekylls and Hydes with which we've got to go through life are determined for us long before we've had any chance of influencing the chemistry....To judge people by one pattern--and, as a rule, the pattern most convenient to the judges--is the hopeless mistake so many of us make. There are millions of patterns. We don't all start even....One can't see in the darkness....I expect [the villain's] excuse [for his villainy] is that he's never been given a light....

This generous and optimistic social philosophy is a direct descendant of Charles Dickens and Farjeon's father, who represented the generous and optimistic side of Victorianism. (For more on this, and the more crimped and pessimistic opposing side, see this Crimereads piece by me.) It's a world away, I think, from Sapper and his followers, whom Farjeon might be chiding here in this passage:My theory is that sneaks and listeners often crumble into dust if you give them one good square British bulldog look!

Yes--that would be your theory.

Farjeon's hero agonizes about whether he can call the pretty girl by her first name, a scruple I find charming in this age when people use your first name immediately upon meeting you, whjether you want them to or not.

So there's a great quaintness to Farjeon's niceness. Farjeon is the nicest thriller I have ever encountered. Sometimes this quality may undermine the thrills, but it makes reading him withal a pleasant experience.

A few days before Christmas 1954, less than six months before he died at the age of 72, Farjeon in a newspaper letter concerning the recent controversial airing of a television adaptation of George Orwell's bleak futuristic dystopian novel 1984, took issue with Orwell's representation that human nature could be so remorselessly manipulated and transformed:

[I]n Orwell's grim conception, the spirit of man had no reality, and instead of glowing from an eternal source, it can be snuffed out like the flame of a candle. That surely is not true.

I share the belief that evil is self-destructive, while good goes on....I think there is only one answer we can give to [the problem of evil]...to attend to our own hearts....When enough of us do this the world will not need to to worry--nor will it require armies.

How Dickensian a view, as George Orwell would have said. In fact, Orwell did say it.

Farjeon did lose faith once, in his own grim apocalyptic novel Death of a World, a superb though sad book published in 1948, a year before the Russians tested their own atom bomb. But his crime thrillers are hopeful and comforting. If there is such a thing as a cozy crime thriller, Farjeon wrote it. He was also a natural writer, making his books invariably good reads, even when the plots seem on autopilot. Highly prolific mystery writers have to come up with plot after plot, year after year, we must recall, and these harsh authorial regimes can wear out a mystery writer. Even Christie and Carr and Queen were worn down eventually. During his thirty-year crime writing career, Farjeon did come up with some excellent plots, however, and they grace his best books. I will review one of those next. It's the beginning of the end. And the end of the beginning.

As ever a fascinating " review ". I am sorry that your promotional endeavours didn't bear fruit with this author ; however readers of Bush/Rutland/ Dalton to name but three should be grateful for your other work ,to say nothing of your important books.

ReplyDeleteI have always found Farjeon to be a most enjoyable read . Not always on top with alibis/red herrings / big plot twists etc etc. I do want to turn the pages though and there are so many clever and witty paragraphs to go along with an often skilfully written atmosphere in all sorts of dwellings . I only leave the " Ben " books as I find pages of mockney dialect to become tiresome.

Just reissued ( and not on your list as it isn't an overt thriller ) is " Return to Victoria " from 1947 . A book which encapsulates so many of Farjeon's endearing qualities. Please keep up all your tireless work with all aspects of GAD fiction.

Thanks, Alan, you have always been a good friend and a great reviewer. Farjeon's Macdonald series of hybrid books is delightful. Want soon to post on his Murder at a Police Station, one of my favorites by him, and am rereading Mystery of the Creek, more conventional but still entertaining.

DeleteSome people thought this was a valedictory post, but it really wasn't intended as such. It's just been so hard in my life since my beloved Dad's death. I get very depressed at times, but I want to keep the blog going. Since he died I have written four intros, including one for Mysterious Press, so am trying keep my pecker up, as it were. But I am feeling tired more, tired and down and depressed. I always try to tell myself it was worth it.

Not a hint of valedictory posts please. ! Just count the number of introductions you have done ,then add the published books; I would call that an impressive body of work. Perhaps now, consider a few new avenues to explore and try a few new ventures . Always difficult when a parent dies; perhaps though some new ideas will flow ;remember the symphonies that Shostakovitch wrote under the direst of situations !!

DeleteBut how happy a person was he? That society took its toll on him, didn't it. Of course we are told that adversity is good for art. As long as one isn't too depressed to do it. I have had a bad couple of days for varying reasons, but I finished another Farjeon, one of his more formulaic ones, to be sure, but still enjoyable. What I find interesting with him is how his writing became more sophisticated in the late Thirties and the Forties, it seems to have been a trend in English crime writing at that time. There are some books he did that are much more originally plotted, with more real detection, and I want to write about some of those. I think BL didn't highlight this enough, though Thirteen Guests is one I like a lot.

DeleteThe standard Farjeon "No. 17" thriller plot was to put some people in a creepy locale (house, inn, windmill) in an isolated location and pit them up against come crooks with a mysterious agenda. Some are better than others. Mystery in White was maybe the culmination of these. What I like is how he chooses unusual heroes for thrillers: meek clerks, secretaries, old men, old women, children. the middle-aged, the mild and meek. One gets tired of Sapper's hulking he-men. Farjeon gave the rest of us a chance to shine.

Glad to see you're not abandoning us. Before you do go though, could you give your long-promised (2011!) review of "The Four Tragedies of Memworth" by Lord Ernest Hamilton? You seem to be the only blogger who's read it - or is it so bad that its very mention is anathema?

ReplyDeleteI've known where the book is all this time too, just forgot. Will try to hold onto it during the move and read again when from my new place. It's not bad as I recall.

DeleteThanks. I look forward to seeing why Knox exempted Lord Ernest from his Sinophobiaphobia.

Delete