Mona Naomi Anne Hocking Dunlop Messer, or Anne Hocking as she is best known, was one of three daughters of native Cornish novelist and Methodist minister Joseph Hocking, a very popular author in his writing day (this being 1887 to 1936), though he has not gotten a great deal of attention from literary critics, on the whole. Joseph and his brother Silas, along with their sister Salome, were purveyors of "pulp Methodism," as one critic who has studied them has called it: popular fiction with a decidedly evangelistic, sometimes anti-Catholic tone. I don't know what he made of Anne's penchant for more secular crime fiction, but he did leave her his money when he died in 1937 at the age of 76.

Anne's sisters wrote some mystery fiction as well, under the names, respectively, of Elizabeth Nisot and Joan Shill, but Ann, the eldest of the trio, was by far the most prolific. (There was a brother as well, Edward Cuthbert, who died in the Great War, tragically but a couple weeks shy of the Armistice.)

Anne was born in late 1889 and died in March 1966, like her father at the age of 76, four years after having suffered a debilitating stroke while she was working on her thirtieth Inspector/Superintendent Henry Austin detective novel, Murder Cries Out. (It was completed two years after her death by Evelyn Healy).

Like Agatha Christie, Josephine Bell, Elizabeth Ferrars and other British women mystery writers of the era, Anne wrote "middlebrow" mainstream novels as well as mysteries, under her married name (at the time), Mona Messer, though she started out in 1930 and 1931 with a pair of what might be termed updated sensation novels, or crime thrillers with a Gothic overlay, concerning naive, young Englishwomen in peril in ancient aristocratic piles on the wicked continent. (Actually there was an abortive first novel fifteen years earlier, written under her married name at that time, Mona Dunlop, but it made little impression.)

As Mona Messer she then published eleven mainstream novels between 1932 and 1940, but during this time she was also publishing more thrillers, now under under the name Anne Hocking. There were a dozen of these crime shockers published between 1933 and 1941. (We are up to 25 novels between 1930 and 1941; but wait there's more, as they say in the infomercials.)

The most significant of these thrillers, arguably, was a 1938 number called The Little Victims Play, for it introduced Chief-Inspector William Austen, who would become Hocking's series sleuth in 29 later detective novels, published between 1939 and 1968. It's a convoluted evolution, but an interesting one.

Anne around the time of the Second World War seems to have deliberately eschewed crime thrillers in favor of the manners mysteries associated, with rising critical approval, with Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh, authors to whom she refers admiringly in her own crime fiction. (Patricia Wentworth, it should be noted, had a similar evolution to Hocking, decisively committing to the Miss Silver mysteries around this time and relenting from writing more of her thrillers.)

I don't know that I would call The Little Victims Play a thriller, however. It's really an inverted detective novel of the sort that Julian Symons called the "Iles School" after Francis Iles, though Francis Iles did not originate it. The book concerns an aunt and her niece who check into a seaside place, the Avon Hotel, in Cornwall, with fatal results for the aunt. I'm not telling you anything you don't learn on page one, for it states there, in the first sentence:

When Miss Selby signed the register at the Avon Hotel she was signing her death warrant....

Fatefully in Chapter One fifty-year-old Miss Selby meets dreamy Geoffrey Harden, an ex-army man about five years younger than she:

He was...tall, rather over six foot, broad and spectacularly handsome in a florid, full-blooded way. His eyes, black and liquid, were set under heavy black brows, his nose was almost Grecian and his very red, full lips curved seductively over gleaming teeth....at probably somewhere about forty-five, he was beginning to put on weight, not aggressively, but sufficiently to blur his outlines a trifle, to produce the slightest effect of coarseness in his ruddy face.

Men who are a little too handsome in English mysteries are usually bad news in some form or another. Is Major Harden? Well, read it and see (assuming it's reprinted, as right now copies are rare as hens' teeth). I will divulge that the Major and Miss Selby get hitched, and the niece, Merryn Lynton, is not happy about that!

After Miss Selby dies, in rather suspicious circumstances, Inspector Austen of Scotland Yard is consulted, strictly off the books, about his opinion of the affair. He only appears in the last fifth of the book, mostly in one chapter, functioning mainly as the copus ex machina with handcuffs.

There's some interesting detail about poisoning in this book, for which the author credits doctors George Trustram Watson and Frederick Denison "Denis" Maurice Hocking, chief pathologist of Cornwall for half a century and doubtlessly a family relation. She modestly dedicated the novel to her sisters Elizabeth Nisot and Joan Shill, "Because They Like This Kind Of Thing."

Did I like it? Well, it's a quick read and has its points, but on the whole I prefer Anne Hocking's straight detective tales with Inspector Austen: they feel like they have more meat on their bones. One thing there is that struck me, however....

Victims takes, to be sure, rather a pessimistic view of relations between the sexes, with the classic scenario of a plain middle-aged woman newly come into wealth being preyed upon by a designing male anxious to devour her lucre.

Nevertheless the author stresses that Major Harden did in fact make Miss Selby deliriously happy, while she lived. "Gertrude had gone to her grave thanking God for a perfect husband," observes Hocking trenchantly. "Not many women do that."

This set me to wondering about the author's own marital history. Well, it seems that Anne Hocking married twice, the first time at age twenty, after a year at Royal Holloway, a London women's college, to Frederick William Dunlop, a 26 year old native Scottish chartering agent and shipbroker. Dunlop died four years later, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, leaving his widow just seventy-six pounds, or about about ten thousand dollars today.

|

| Handsome Howard Messer, one of the author's brothers-in-law from her second marriage to Henry Messer |

The next year Anne published her first novel, to little acclaim or attention. Three years after that, near the end of the war, Anne, now twenty-eight, wed forty-six-year-old Henry Richmond Messer, a stockbroker, a man old enough to be her father, as they say. Messer came of a prominent family, his late father having been John Messer, a timber, brick and tile merchant and mayor of Reading. When he died in 1900 Mayor Messer left an estate that would have been worth some 3.5 million today.

One of Henry's brothers was a prominent Caribbean lawyer, another a mining engineer in South Africa and two were prominent expat architects in Fort Worth, Texas. All the men in the family seem to have loved traveling and boating. A youthful picture of the younger of the architect brothers, Henry, shows rather a handsome man, like our Major Harden from Victims.

|

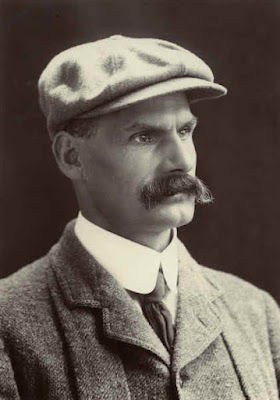

| Joseph Hocking, Anne Hocking's father I don't believe he ever learned to smile for a photo |

Two clues suggest, sadly, that Anne's marriage to Henry Messer may have ended in personal estrangement. Remember that Anne took up writing again, most prolifically, in 1930, a dozen years after the commencement of her second marriage. In 1937, when her novelist father Joseph died at St. Ives, Cornwall, he left his entire estate, 5310 pounds, or over 458,000 dollars today, to Anne, referring to her in his will as a widow.

It was so nice of dear papa to help his daughter out this way, but it turns out that Henry Messer actually died during the Second World War in 1943 at the age of seventy-two in Durban, South Africa. He left his estate to Anne, who was living in England--all of 104 pounds, or about 6275 dollars. Looks to me like Henry had separated from her, at least six years previously, probably rather more.

Perhaps Henry provided Anne some years of happiness before then, or maybe not. In any event Anne relaunched her writing career, to the good fortune of her readers. She actually entered her best writing phase after her father's death finally left her financially secure and independent, for the first time in her adult life. Perhaps Virginia Woolf was right about a woman writer needing a room of her own....

There is, by the by, some discussion of God's will in Victims, which Anne would have written during the last year of her pious father's life. Merryn and her doctor boyfriend debate whether she is too vengeful and vindictive toward Major Harden, usurping God's prerogative. But don't let that worry you: on the whole The Little Victims Play is mostly just another nice Golden Age English murder story.

No comments:

Post a Comment