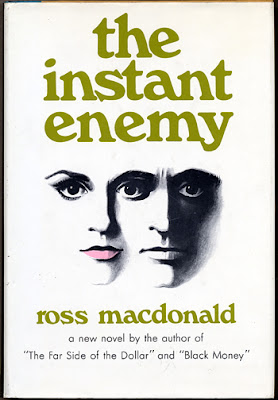

Black Money (1966) is my favorite Ross Macdonald novel from the 1960s, in part because it steers away from the intricate, indeed dizzying, genealogical family dysfunction puzzles so prevalent in the author's books at this time. An example of the latter sort of tale is found in another one of Ross Macdonald's Sixties crime novels, The Instant Enemy (1968), a tale which also involves another hugely important element in Macdonald's crime fiction from this period: fatal misunderstandings between parents and children, or the generation gap, as it was being called back then.

In a Commentary review (1 Sept. 1971) of Macdonald's The Underground Man, Richard Schickel, until a few years ago the longtime film critic for Time magazine, noted the late Sixties/early Seventies critical embrace of Ross Macdonald as a "serious writer" who "transcends the boundaries of his genre" (fueled by a Newsweek cover story and major reviews in the New York Times Book Review from William Goldman and Macdonald's intimate epistolary friend Eudora Welty).

Schickel pointed out that the crime writer's multi-generational crime sagas of family deceptions and dysfunctional behavior had caught the tenor of the times, even though he, Schickel, did not think that Macdonald's books deserved all the praise as Literature that was then being heaped upon them. For my part, I have a much higher estimation than Schickel of Macdonald as a literary writer, yet I don't enjoy quite so much as many of Macdonald's admirers the pattern that his mysteries so frequently fell into in the 1960s and 1970s. For me, as with Schickel, the books do get too repetitive.

Even Macdonald's series sleuth, PI Lew Archer, declares early on in The Instant Enemy: "I was weary of the war of the generations, the charges and countercharges, the escalations and negotiations, the endless talk across the bargaining table." Archer has ample reason to make this declaration of weariness, for The Instant Enemy offers a great example of the pattern that so obsessed Macdonald. (It's one that also dominates his much-praised follow-ups, The Goodbye Look and The Underground Man, the latter adding the plot wrinkle of California environmental devastation, seen as well in Sleeping Beauty, the penultimate Macdonald mystery.)

In The Instant Enemy Lew Archer initially finds himself embroiled in a missing persons case. Not surprisingly, the actions of unhappy young people start the investigative ball rolling. This time, Sandy Sebastian, seventeen-year-old daughter of Keith and Bernice Sebastian, has disappeared. Archer again finds himself haunting his usual surroundings--unhappy domestic abodes of the professional business classes (in his review Schickel rightly notes Macdonald's "obsession with the upper middle-class and rich")--and acting as much as family counselor as shamus.

Sandy had become moody and unhappy, confiding her feelings in a diary that Bernice Sebastian tells Archer she has destroyed and will not discuss with him. She and her husband think that Sandy has run off with Davy Spanner, a nineteen-year-old boy with even more emotional baggage than Sandy, and they want Archer to get her back. Thus tasked, Archer embarks on a labyrinthine case involving much criminal mayhem and revelation of shocking family secrets.

As with The Goodbye Look I felt compelled at one point in The Instant Enemy to make a chart of all the extended family members and purported family members across the three generations, as there was so much inter-generational complication and deception occurring in the novel. For me Macdonald's greatest strength as a crime writer lies in (besides his sense of empathy for the emotional travails of human existence) his sheer skill at devising complex puzzle plots.

In his essay Richard Schickel astutely observes that Ross Macdonald "is something a detective story classicist" and that, despite Macdonald's elevation with Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler to the great American hard-boiled detective fiction triumvirate, his fiction is closer to the the "whodunits of Agatha Christie, Rex Stout, Ellery Queen, and the other masters of the purely ratiocinative school."

Like these renowned classic detective fiction authors, argues Schickel, Macdonald deals with murder within a "closed, and closely related, society," upon which the detective descends "to punish the transgressor" and restore innocence, whereupon s/he retires from the scene. (Schickel here explicitly draws on "The Guilty Vicarage," W. H. Auden's famous essay on classical English detective fiction.)

I think there is a lot of truth in this assertion, although I also think it must be admitted that Macdonald (like P. D. James, a great admirer of his) allows quite a lot of emotional wreckage to take place before Archer successfully navigates his ship to shelter from the criminal storm.

Black Money has many of the ingredients of The Instant Enemy, such as misery among the wealthy and an intricate plot implicating misdoings from the past, but it feels more original because here Macdonald found an additional wellspring of plot inspiration to family dysfunction.

As others have noted, with Black Money Macdonald was influenced by The Great Gatsby (1925), a classic American novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald. (Another author who seems clearly to have based a crime novel on what might be termed the "Gatsby legend" is Ruth Rendell in Going Wrong (1990); Black Money I find inestimably a better book, however, despite my admiration for Rendell's crime writing in general.)

In this novel Archer is hired by an affluent young man to look into the questionable background of a dangerously suave Frenchman who has run off with the young man's beautiful girlfriend. Quite a hornet's nest is stirred up by the detective in the process, including much mystery surrounding the seven-year old drowning death--purportedly a suicide--of the girlfriend's father.

Much of the case takes place within the milieu of the wealthy Tennis Club society of Montevista, California (where people "play at being simple villagers the way the courtiers of Versailles pretended to be peasants"), which gives the book rather a fresher feel than The Instant Enemy, in my view. The novel also has some of the most memorable and moving closing lines Macdonald ever devised.

Both these Macdonald mysteries are well worth reading, but it is Black Money that would get my vote for one of the best modern (1960s onward) "classical" detective novels by an American author. I would urge fans of classic crime fiction--and fans simply of good fiction for that matter--to read it, if they haven't already. In August it was announced that the Coen brothers are interested in developing the book into a film--I certainly hope this event comes to pass!

Really enjoyed this post Curtis, thanks, especially for all the great context as i'd not read Schickel's piece. Have you read the Ralph Sippen's tribute to Macdonald, INWARD JOURNEY? Really fine little volume of essays. I agree, BLACK MONEY sees the author at his best (though I would add THE CHILL as probably his best overall). His does return to that theme of the family past over and over - but I love what he does with it.

ReplyDeleteNo, I haven't read it, have to find it! Black Money is really my favorite of his Sixties books. I think there's only one of those left that I have not read. He does the inter-generational family dysfunction plot well, but it's nice to see him varying it a bit in Black Money, at least for me.

Delete"His does return to that theme of the family past over and over - but I love what he does with it." Absolutely.

DeleteThanks for this judicious analysis, Curtis. I agree that Black Money stands apart from his other novels with its originality (I for one remember fondly the 5 questions to test the Frenchness of Martel that contain a deeper meaning). However, I think the pivotal novel is the Galton Case that started Ross Macdonald on the theme of family secrets deeply buried on the subconscience of children.

ReplyDeleteWe would like to know more of your thoughts on Ross Macdonald.

I agree that The Galton Case is hugely important for starting him off on his new track, so prominently marked in the 1960s and 1970s. I'm not sure he ever bettered The Galton Case, in terms of his handling of the theme of those deeply buried family secrets you mention. I've read all but one of his sixties books now and plan on reading that last one this year.

Delete