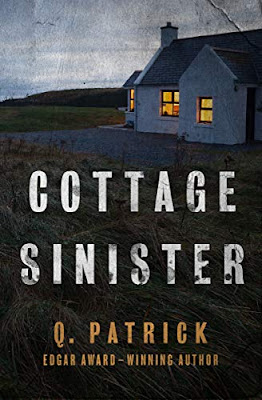

--an English review of Cottage Sinister, by Q. Patrick

|

| Contrary to this post-WW2 Swedish English-language edition, Did the "Q." in Q. Patrick really stand for Quentin? . Patrick also was Patrick Quentin |

Sometimes you read about debut mystery writers producing a fine first mystery, taking flight on the wings of some brilliant central idea, unfortunately following it with the product of a "sophomore slump." In the case of Q. Patrick, however, the slump came first, with the first mystery, Cottage Sinister (1931), being rather a curate's egg, happily followed by an excellent second tale, Murder at the Women's City Club (1932) (Death in the Dovecote in the UK).

The marked improvement can't be attributed to a change in authors, because these initial Q. Patrick novels both were written collaboratively by the same people, Richard "Rickie" Wilson Webb and Martha "Patsy" Mott Kelley. I chalk it down simply to experience. The more you write, if you have any hope as a writer at all, the better you get at it.

Of course readers of this blog should know all about Rickie Webb at this point. Born in England, he graduated from Cambridge University in 1924, spent some time during the Roaring Twenties in Berlin, Paris and South Africa and then finally ended up ensconced in Philadelphia, City of Brotherly Love, where he would take an executive position with the pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline and French (makers of Benzedrine inhalers) and reside from the late Twenties throughout the Thirties.

When Martha Mott Kelley, a recent graduate of Radcliffe who had already published short stories and book reviews and was a niece of prominent progressive social reformer Florence Kelley, joined forces with Rickie in 1930 to write detective fiction, they coined their pseudonym by shortening their nicknames "Pat" and "Rick" and adding in front the letter "Q," which they pronounced the most interesting letter of the alphabet. Really? "Q" rather than the mysterious "X" or the elusive "Z"? Well, I have my own theory as to why Rickie, anyway, thought "Q" was so interesting.

Their first mystery, Cottage Sinister, has all the trappings of a classic English village mystery, but something about it just doesn't work like it should, in my view. That notorious mystery-hating scold Edmund Wilson once accused Ngaio Marsh, a New Zealand native who wrote mysteries mostly set in England, of populating one of her novels with a bunch of "tricked-up" English country people; yet while Marsh's country people may or may not be fully accurate representations of the England of her day, her books to me nevertheless at least feel truer to real life than those in Cottage Sinister.

I don't know whether Patsy Kelley, who came from a prominent Philadelphia Quaker family (famed abolitionist, feminist and pacifist Lucretia Mott was a relative), ever had visited England, but Rickie, who was the son of a headmaster, spent the first 23 years of his life there, and Cottage Sinister is even set in the part of England whence he came.

I think the problem may have been that for whatever reason the pair decided to make their England the deliberately artificial England of books, the England about which they thought the readers, whether in the US or the UK, wanted to read. JJ Connington did the same thing with his first British mystery, which similarly felt false to me. So maybe they succeeded in what they were trying to do, but I think trying to do it in the first place was an error of judgment. It's just too twee really to be.

In Cottage Sinister, explicitly set in 1930, we have murder in the quaint village of Crosby-Stourton, located in a valley in Somerset, Rickie's native county. But Crosby-Stourton is rather less wide awake than Rickie's Burnham-on-the-Sea:

As it lay somewhat off the main road that runs between Bridgewater and Bristol, it had not yet been discovered by the American tourist or the marauding automobile, and its rustic charm was still unspoilt by the flamboyant road-signs and advertisements which are assiduously defaming the English countryside in their attempt to inflict unwanted goods on an unwanted public.

Harrumph! In this stodgy, slumberous village, we have, naturally, a local country landlord of ancient family, Sir Howard Crosby, the eleventh baronet, "a good landlord if somewhat severe and unbending." His son Christopher, however, "the young squire and future baronet," is studying medicine in London, with the aim of practicing as a doctor. He's such an odd duck, indeed, that, saith the bemused villagers, "he do talk to us poor folk as though he were nobbut a plain village lad and not one of the gentry at all." Imagine! Must be one of they Bovrilvikings you hear tell about in that there heathen Russia, I reckon.

And that's another thing I didn't really like about Cottage Sinister: the abundance of dialect speech, whether it that sort of Mummerset above or some excruciatingly heavy cockney speech that the authors manage to drag in. As I see it the emphasis on "colorful" dialect speech in Golden Age mystery only serves to make unreadable lengthy passages of text spoken by cheeky London cockneys, lofty Scottish lairds, Cape Cod fisherman and black Americans, the latter whether they reside in northern cities or in southern plantation country. Good writing, in my opinion, doesn't need such crutches. Step lightly, I say!

Golden Age mystery writers spent a lot of time on this sort of thing, time which would have been better spent plotting better mysteries. Even the most famous names in the genre, like Dorothy L. Sayers, Michael Innes and Gladys Mitchell, prided themselves on rendering unto their poor readers ostensibly authentic (and nearly unreadable) local dialect. Although he was not nearly so good a detective novelist as those others, Milward Kennedy, I will say to his credit, hated it. He was right.

Worse yet, there are malapropisms. One of Lucy's less educated sisters says "internals" when she means "interns," for example. The worst offender in this respect is the comic village constable, but naturally, who I was hoping would be one of the murder victims before the tale was over. This is how he converses:

"I was hambulating 'ome past Lady's Bower on Sunday evening at about six o'clock--while they must 'ave been 'aving tea inside--and the hindivdual was as it were 'anging on the garden gate."

"Did you speak to him?"

"No sir. But I fixtured 'im with my eye. Might 'ave been about fifty, say. 'E was a bit dressy, you know, like a gentleman, but you never can tell because sometimes these rapscalliwag poachers....

|

| nothing like this scene happens in the novel as I recall |

Anyway, back to nobbut Crosby-Stourton! There is also a Lady Cynthia Crosby, who has given her loyal old nurse, Mrs. Lubbock (who long had to care for Lady Crosby's crotchety, wealthy invalid mother), a generous pension and the use of Lady's Bower, the loveliest, quaintest cottage in the village. Additionally Lady Crosby has made a protege of Mrs. Lubbock's youngest daughter, Lucy, giving her "the best of educations, and finally equipping her for the profession of nursing, her chosen field."

Of course this proficiency makes Lucy suspect number one when the poisonings at Lady's bower commence. There are also poison pen letters, did I mention? Verily, this is the English village mystery that has everything, barring some silver--Miss Silver I mean.

Lucy is now a lovely and highly competent nurse in the Village Hospital, where naturally she is resented by all the locals, who of course feel that Lucy has been "educated above her station" (that phrase gets used numerous times), upsetting the social system of this reeking feudal section of England, where a small segment of the population is entitled to own and the much larger segment required to serve. Just how we like it in our Golden Age English mystery!

I knew a girl in middle school who liked reading mysteries, but she always felt cheated unless there were two murders, preferably three (or more). Well, she would have loved Cottage Sinister, where there are four deaths. All poisonings too, as indicated above. Rickie, a pharmaceutical executive as I mentioned, did know how to ingeniously poison people, to be sure.

And for that matter the basic mystery plot is rather nice, although the motive which the investigating man from Scotland Yard, Archibald Inge (known as the Archdeacon because of his resemblance to a higher churchman), attributes to his #1 suspect, the beleaguered Lucy Lubbock, is beyond absurd, literally nonsensical. He, "no socialist but a devout believer in the divine right of the landed gentry," deserved to fall flat on his face in the end, nobbut else can I say.

I will give Rickie and Patsy props for recalling, with the name Archibald Inge, England's famed churchman Dean Inge (1860-1954), who was criticized for being a medievalist in his social philosophy. Also, it's possible that Rickie in Cottage Sinister had the bizarre--and still unsolved-- 1928 Croydon Poisonings in mind.

In short, Cottage Sinister seems to me a case of a novel of promise, had the authors gotten the trimmings right. As it stands, it's only "good in spots." Happily, there followed Murder at the Women's City Club, which is set not in Merrie Olde England but in America's City of Brotherly Love, Philadelphia (though the it goes under another a name in the book). Both authors knew this setting well, Patsy Kelley having grown up there and Rickie having lived there for the last five years, and it shows. In future most of Rickie Webb's novels would be set in the US, and they are none the worse for it.

But then on Amazon the new Open Road edition of Cottage Sinister has two reviews, both of them for five stars, so Rickie and Patsy may have been on to something. What do critics know, anyway, right? Cheeky buggers they be!

Coming soon, Murder at the Women's City Club. It's been favorably reviewed by some percipient bloggers, to whom I will provide links, but I think I have some new things to say about it.

I had the same opinion as you on this one. It was rather a slog to get through which was a surprise coming from these writers. I haven't heard of the other book you mentioned. I guess I'll have to give it a try, though currently the only edition available at Amazon is $247. Have you ever noticed how the book you want most are ridiculously expensive, but if you splurge for one it comes out as an e-book about six months later.

ReplyDeleteI sent Open Road an email about the Webb-Wheeler reissues, but I never heard back from them. I think they have brought all the Q. Patricks back in print except Club and the last one, Danger Next Door, which are the rarest. I would have been happy to have made my copy available for scanning though maybe I should hold out for selling it for a huge discount for $250. Actually my copy is in better shape than the one you're talking about, lol.

DeleteJohn Norris has the same opinion of Cottage Sinister as you and I do. It's frustrating because it's one you feel really should hit it out of the park, but it doesn't. But the second one is a lot bettter, imo. I hope Open Road reprints it. There might be one issue that would cause problems for a modern day audience, which I will get into in the post.

Hello Curt! I read your review of COTTAGE SINISTER with interest, but with one eye closed and skimming over the plot details, as I still want to read this story, even with your caveat. Also looking forward to your review of WOMEN'S CITY CLUB, which I found very enjoyable. Thanks so much for all of the wonderful information you've presented on the multiple writers behind the Q. Patrick/Patrick Quentin/Jonathan Stagge books!

ReplyDeleteI don't believe I come remotely close to spoiling anything in my review, in fact the opening quotation from the other review has more of a spoiler than I do and that's not really a spoiler either. I suppose you, John and I are the only people in the world who own this book, lol. Even Otto Penzler doesn't have it, apparently!

DeleteMurder at the Women's City Club, I mean.

DeleteHello, and sorry for the late response to your reply; work has been all-consuming this week. I wish I owned WOMEN'S CITY CLUB, but I was grateful to get it from the college interlibrary loan system. It's a title that is well worth a reprint! As for your spoiler-free COTTAGE SINISTER post, it undoubtedly is. I'm the type of person who likes to approach a mystery knowing absolutely nothing about the plot, if possible. That even includes the basic set-up, a la "Sir Carleton is found murdered in his study with a curious clue on the table beside him." I want to be surprised by victim, locale, and clue if possible. That's what I meant by skimming over the details; that's just reflexive on my part! All best -- J.

DeleteI never bothered finishing this one. I loathed the chit-chat dialogue in the first chapter. Everyone seemed such ninnies. Maybe I should give it another try. I did however, fully enjoy ...WOMEN'S CITY CLUB. I may own the only copy of the UK 1st which has the alternate title DEATH IN THE DOVECOT, a metaphoric title that doesn't really suit the book or its story.

ReplyDeleteNo, the authors mention "dovecot" twice in the book (or dovecote), but it doesn't really suit, does it, despite being more alliterative. Who was the English publisher? I think there was a lot of improvement between the first and second books.

Delete