"Tall--over six feet--and one of the thinnest men I've met.

Andy shook his head gloomily. "Nobody sees him come, nobody sees him go. What was that joke about a guy being so thin he has to stand in the same place twice to throw a shadow?"

--The Thin Man (1934), Dashiell Hammett

It's customary for modern critics to pronounce that Dashiell Hammett's fifth and final completed novel, the mystery The Thin Man, is the "weakest" of all his books. Although he found The Thin Man a "continuously charming and sparkling performance," fervent Hammett admirer Julian Symons, for example, detected in it evidence of "a slight decline." Most professional opiners compare the novel unfavorably to Hammett's earlier works, particularly Red Harvest (1929), The Maltese Falcon (1930) and The Glass Key (1931), which starkly portray grittier, darker criminal worlds.

I don't know that The Thin Man is the ninety-eight pound weakling, if you will, in Hammett's output, so much as it is deliberately light stylistically, but to most crime fiction critics--such serious and sober people they are--darkness inevitably covers light. (I'm sure nine out of ten critics would tell you that they far prefer to Hammett and Raymond Chandler to Rex Stout or Ellery Queen, for example.)

At the time, however, critics applauded Hammett's latest novel and the public lapped it up like champagne. The Thin Man sold 32,000 hardcover copies in its first year in print, this at a time when mysteries ingloriously averaged merely 2000 sales in hardcover, mostly to rental libraries; and it spawned the famed Thin Man series of six films, all of them starring William Powell and Myrna Loy as the wise-cracking, hard-drinking series husband and wife detecting team, Nick and Nora Charles.

The success of The Thin Man, novel and films, created the vogue for bright and sophisticated "couples" sleuths in the United States, although one might argue that across the pond Agatha Christie had laid the predicate for this sort of thing back in 1922, when she introduced her flippant amateur snoopers Tommy and Tuppence in her second mystery novel, The Secret Adversary. Hammett's admiring public had stuck with him through the early novels, where blood ran thick indeed, and I have no doubt that they would have stayed with him had he opted to write a series of Thin Man novels over the course of the Thirties. Instead he contributed a couple of screen treatments for the next two Thin Man films, which were reissued in 2013 as "novellas," a misleading claim. (Perhaps some enterprising modern mystery writer should rewrite them as such.)

And then there came silence, aside from a mainstream novel, Tulip, which Hammett desultorily worked on for two decades and never completed. I think that Hammett, like a lot of talented crime writers, felt the urge to become a "serious writer," but could never pull it off; so instead his energies when into booze and left-wing political activism. It was a huge loss to mystery fans. But certainly Hammett never became a "hack" novelist. His integrity's gain is our enjoyment's loss.

With The Thin Man there is always the danger of letting memories of the charming and frothy film series manipulate one's memories of the book. Hammett's novel is not "screwball," as much of the film couples mysteries of the Thirties were, it is much more sexually explicit, and it has a certain ribbon of darkness twisting through it. It's a long way from the world of Red Harvest, to be sure, but Hammett addicts can still tell, while perusing it, that they are addicts in Hammett-land.

When the novel opens in the dying days of December 1932, Nick and Nora, who reside in San Francisco, are visiting New York for Christmas, seemingly spending most of their time lapping up liquor at their hotel suite and myriad speakeasies. Forty-one year old Nick Charles (aka Charalambides) is a retired private detective who six years earlier married lovely Nora, an heiress fifteen years younger than himself. After the marriage her father died (naturally, I hope) and Nick quit the detecting biz to devote himself, when he isn't drinking (which is most of the time), to managing his wife's business interests.

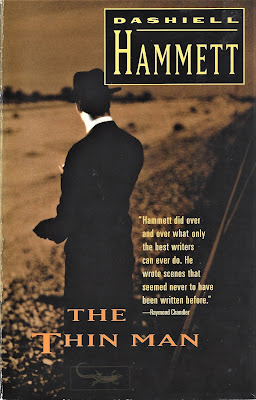

|

| 1992 Vintage Books edition |

Nick suggests that Dorothy try contacting her father's attorney, Herbert Macaulay. Then in comes Nora, with her and Nick's dog Asta--who unexpectedly for fans of the films is female and a Schnauzer--in tow. Out goes Dorothy. As the chapter closes, Nick and Nora have this conversation, which is typical of their lively patter throughout the book (and had to be toned down for film):

Nora said: "She's pretty."

"If you like them like that."

She grinned at me. "You got types?"

"Only you darling--lanky brunettes with wicked jaws."

"And how about that redhead you wandered off with at the Quinns' last night?"

"That's silly," I said. "She just wanted to show me some French etchings."

Two days later Clyde Wynant's secretary, Julia Wolf, is discovered shot to death at her apartment by Dorothy's mother Mimi Jorgenson (formerly Wynant), who had come to pay a call on the secretary concerning the whereabouts of her ex-husband. So who murdered Miss Wolf?

A leading suspect is Wolf's boss, Clyde Wynant, the "thin man" of the title, who may have been her lover as well. But Clyde has been absent from New York since October and cannot be located now, although he periodically sends letters to his lawyer and there are various people who claim recently to have seen or heard from him. Booze-guzzling Nick wants nothing to do with the case, but he keeps getting dragged into it by Clyde's screwy family, as mixed-up a bunch of Freudian head cases as you will ever find in a vintage mystery.

|

| Mimi and her "little white whips" |

However, it seems like the Wynants, or Jorgensons, could use the services of a good head shrinker. Young Gilbert, a callow intellectual ("His head's so cluttered up with reading"), seems fixated with his own mother, while Dorothy is seethingly jealous of Mimi, who is Nick's age and still head-turningly attractive.

As for Mimi herself, she seems to get some kicks, if you will, from beating her daughter, of whom she is jealous in turn. "You must come over to our place some time [echoing Mae West?] and bring your little white whips," Nick cuttingly tells Mimi at one point.

On another occasion he tells Dorothy that her mother "hates men more than any woman I've ever known who wasn't a lesbian." To lawyer Macaulay, Nick sums up the Wynants' problems in a single memorable line: "They're all sex-crazy, I think, and it backs up into their heads." Freud might not have put it quite that way (Ach!), but the train of thought arrives at the same place in the end.

The most famous of these sexually frank lines from the novel also involves Mimi, who certainly is a femme fatale in nature, whether or not she is one in fact. Nora, who is a rather tough little number herself, asks Nick, after he tussles with a furious and violent Mimi, "when you were wrestling with Mimi, didn't you get an erection?" Nick, responds "Oh, a little."

Although Hammett's publisher Knopf was able to make hay with the controversy generated by this naughty passage, even brazenly directing readers in a newspaper ad to the page where the exchange occurs, it was subsequently excised from later editions, including, amazingly to me, my modern Vintage Books edition. (In the new version Nora euphemistically asks Nick whether he got "excited" when he wrestles Mimi.)

Certainly you won't see Myrna Loy querying William Powell in the Thin Man flicks about his erections, though presumably Nick got them on occasion, since Loy's Nora had given birth to a baby by the third film in the series. In this sense the book is rather coarser than the films, linking them more to the Hammett novels (and to Hammett's own messy and rather sordid personal life).

To many readers at the time, this sort of sexual frankness must have been titillating indeed. Was this the first time the word "lesbian" had ever been uttered in a detective novel? I recall how Hammett supposedly had to sneak the word "gunsel" (meaning young male homosexual) into The Maltese Falcon a few years earlier, yet apparently Knopf gave him no trouble over "lesbian." Nick and Nora also use the words Jesus and Christ as oaths, something you won't be hearing in the film either.

There are gangsters aplenty in this world of screwy sybaritic rich people, though they play subsidiary roles in the tale, as well as cops, who while they are more upright than those you find in Red Harvest, nevertheless routinely third degree and beat up suspects with abandon, so long as they aren't rich. When at one point in the novel Gilbert gets beaten after fleeing and resisting a cop (who didn't know who Gilbert was), he at least gets an apology from the lead police detective.

Also popping briefly up is a stray Communist type (Nick never gets his name), who opines at a cocktail party, "Comes the revolution and we'll all be lined up against the wall--first thing." Nick dryly declares: "He seemed to think it was a good idea." Maybe Hammett did too. Like a lot of writers, I find, he had the ability to stand outside himself and criticize his own behavior, whether or not he changed it. Maybe that's one reason he drank so much. Self-awareness is can do things to you.

|

| the clever couple |

"You do it. I'm going to bed. What's a clue, Mamma?"

Yet Hammett devotes the last chapter of something under two thousand words to having Nick explain all about the murderer to Nora, who amusingly is somewhat skeptical that everything will really wrap up so nicely as Nick thinks it will. For his part, Nick, when Nora asks him what will happen to everyone else in the case, replies "Nothing new....Murder doesn't round out anybody's life except the murdered's and sometimes the murderer's." To which a vaguely deflated Nora replies, "That may be...but it's all pretty unsatisfactory."

Subversive words indeed with which to end a Golden Age mystery! One of the many reasons why you have to read The Thin Man.

"Nick quit the detecting biz to devote himself, when he isn't drinking, ... to managing his wife's business interests."

ReplyDeleteAs the Great Crash happened in between and Nora and Nick are still wealthy, he's obviously pretty good at it.

Maybe drinking helps!

DeleteI think it shouldn’t be overlooked that the untidiness of the plot— the subversive part you note— is indeed the very thesis of the book (yes, it indeed has one). “That may be— but it’s all pretty unsatisfactory,” are not only the final words of the story, but the very point that Hammett is making— that real life (which supposedly he is showing us glimpses of here) is never as neat or symmetrical as that offered in Golden Age detection. And so Hammett purposely includes irrelevant leads (E.g. the beef blood) and unimportant tangents (I know people will find ways to justify the multi-page digression on cannibalism, but it’s not subtle clueing, it’s mean to show the kind of irrelevant digression that real life presents).

ReplyDeleteHammett was really to ensconced in the world of puzzle plotting to lead everything nowhere (and his follow up sequel treatments, before they were thinned out by other writers, were rather thick with traditional clueing), but the central theme of this novel is summarized by Nick’s line “when murders are committed by mathematics, you can solve them by mathematics. Most of them aren’t and this one wasn’t.” And it’s not a particularly satisfactory sense of what I refer to as sudden retrospective Illumination (the confluence of surprise and inevitability) when Nick says “it’s neat enough to send him to the chair, and that’s all that counts.”

All that got lost in the transfer to the screen. Fortunately, what remained— the tangy relationship of Nick and Nora— Has been sufficient to keep people entertained for close to a century now. (Incidentally, the little boy in the photo is Dickie Hall, not Dean Stockwell [who didn’t play the part until Song of the Thin Man]).

“Meant to show” “too ensconced” one day I’ll learn to proofread.

ReplyDeleteUgh, tell me about proof reading. Try it after a 2000 word blog post, ugh again.

DeleteMy apologies to Dickie Hall, who was Dickie Hall? So Dean was only in the last one? I've never actually seen any of the last three.

I totally agree about the cannibalism digression. People want to argue that has some deep meaning, but it didn't require four pages of direct quotation from another book, lol.

I love the mathematics line, reminded me of Dr. Priestley and Dr. Thorndyke, who always solved mysteries like that. My widened mystery reading since I first read Thin Man has made me like it all the more.

I enjoyed this twenty years ago. The "workmanlike and thorough" mystery ... is also the same plot as R. Austin Freeman's Eye of Osiris. As you've pointed out, the hardboiled school liked their Humdrums.

ReplyDeleteI said vintage mystery readers should be able to get the solution before Nick (the other Nick), because the main plot device certainly is not original! Hammett tries to obscure the gambit, but we readers are hard to fool.

DeleteYeah, the plotting in the novel was purposely sloppy to make a point. But that was all lost in the acreen adaptation so that— despite all its real glories as a character comedy— it comes off as merely a poorly plotted example of the type of story the novel was criticizing.

ReplyDeletePlanning a film review next week. Which did you think was the best of the Thin Man film mysteries. I've seen the first three and liked the second best as I recollect, though it suffers from

DeleteSPOILER

Famous Actor Murderer Syndrome--though I guess to be fair you know who wasn't actually famous at the time

END SPOILER