In some ways you might argue Bell did more to humanize the Great Detective than even Dorothy L. Sayers, who, after all, mostly quit having anything to do with Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane after she married them off to each other, referring huffily to the "sentimental Wimsey addicts" who expected her to keep writing about them. Sure we got the wartime short story "Talboys," but there were no novels after Busman's Honeymoon, except an unfinished one, which many decades later was completed by another hand.

The Fifties were an unkind decade to genteel amateur sleuths, with critics like Julian Symons attacking the very idea of such characters as unrealistic and even undemocratic. Professional detectives were the order of the day, and even extremely successful Golden Age mystery writers seem to recognize it. Peter Wimsey vanished, while Margery Allingham greatly cut back Albert Campion's appearances. For Bell's part she published six David Wintringham mysteries between 1937 and 1940 (six in four years), but only six between 1944 and 1958 (six in fifteen years). During the latter period she published four non-series mystery novels, which represented the direction her interest was headed. Twenty-five of her forty-five detective novels were published between 1959 and 1982 and they are mostly non-series, with a few exceptions where she halfheartedly introduced new series detectives, who only stuck around for a few books and weren't much missed when they were gone.

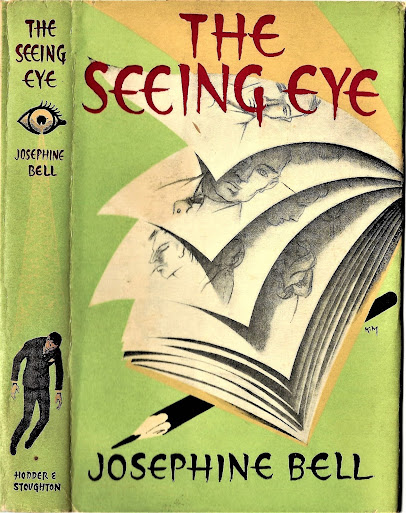

There's an angry young man artist with a sketch book (see the front panel of the splendid jacket, above right) and his self-denying, desperately supportive girlfriend (there are so many of this sort of woman in Fifties mysteries), both of whom benefit over the course of the novel from the well-scrubbed, civilizing influence of David and Jill (and Nanny). But the central mystery is not handled very well, with Bell huddling too much information into the final chapters, making for a confusing and unconvincing solution--at least in my eyes! I can't honestly say much good about this one, even though I have enjoyed Bell's mysteries in the past. (See here and here, for example.) Better luck next time, I hope!

On a happier note, Alan Clutton-Brock's sole detective novel, Murder at Liberty Hall (1941), which I reviewed here three years ago, is being reprinted, by Moonstone Press, with an introduction by me. More on this soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment