Thus, for the tenth time that day, he had worked the twenties, one of the three standard gimmicks of the short con grift. The other two are the smack and the tat, usually good for bigger scores but not nearly so swift nor safe. Some marks fall for the twenties repeatedly, without ever tipping.

--The Grifters (1963), by Jim Thompson

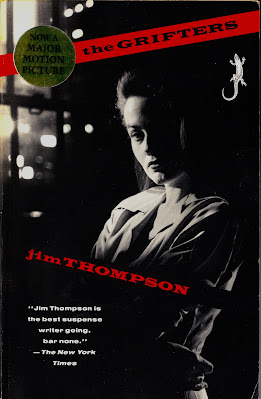

Since in the United States a month ago--Has it been a month already?--Americans elected as president, for the second time, an unashamed, unregenerate grifter, a cynical purveyor of Trump guitars and Trump watches and Trump bobbleheads and Trump bullshit, I thought it would be appropriate to pay tribute to the heinous, YMCA-tripping, old bastard--and the legion of marks who elected him--with a review of Jim Thompson's timeless classic crime novel The Grifters.

If there's a crime writer who knew about rogues and thieves and villains from the poisoned heart of America's heartland, it was old Jim, creator of such classic noir novels about rural psychos and sociopaths as The Killer Inside Me and Pop. 1280. I freely admit to loathing the first of those two books, finding it completely repulsive, but in a way maybe that's a testament to its power. I think Jim had his finger on the elevated pulse of America's dark, damaged heart far more surely than more pious writers, not to mention even that other great J-man, Jesus Himself.

Born in Anadarko, Oklahoma in 1906, Thompson led a wayward life but in his middle age he published a slew of hard-hitting paperback originals in the United States during the Fifties and Sixties that now widely are seen as crime fiction classics. Essentially this run extends a dozen years beginning with The Killer Inside Me (1952) and ending with Pop. 1280 (1964). Along the way some of the author's most famous paperback originals were Savage Night, The Nothing Man, A Swell-Looking Babe, A Hell of a Woman, After Dark, My Sweet, The Getaway and The Grifters.

The hard-living Thompson died at age seventy in 1977 with his books out-of-print and seemingly forgotten, though two of them were filmed in the Seventies. In 1984 Vintage's Black Lizard Crime imprint began reprinting Thompson's novels, in the process catching the jaundiced eye of then influential British crime critic Julian Symons, who adjudged, Jehovah-like, that the American was "no more than an efficient imitator of other writers in the genre, particularly James M. Cain."

Personally I find Thompson's crime writing much more perverse and viscerally horrifying than Cain's. Cain after all was in vogue in the Thirties, while Thompson was pushing the envelope even by Fifties standards. I frequently come across passages in Thompson that I find intensely unsettling--that's not something I can say so much about Hammett or Chandler or even James M. Cain.

But I think Symons essentially dismissed most of American "tough" crime writing after those three greats as simply sex and sleaze. He didn't really like Cain all that much either, complaining of the author's "coarseness of feeling allied with a weakness for melodrama."

No wonder, then, Symons saw Thompson as nothing more than a mere imitator of Cain. You could level the same charges at Thompson were you so inclined; and Symons was so inclined. Some critics were never comfortable with the sex and violence in these books, and Symons was one.

I'm not comfortable with them myself frequently, but then every read needn't be a comfort read. Symons himself dismissed much of British genteel detective fiction as anodyne and he reserved only mockery for cozies. Certainly cozy is not a word you can apply to Jim Thompson's books.

The violence--especially against women--in The Killer Inside Me by the murderous anti-hero is something I personally can't stomach, but I have enjoyed other Thompson novels over the years, increasingly so in the last few as my own life has gotten bleaker and the world has turned dark. If you want to read about sleazes and psychos and dirtbags and louses--which after all is what a good-sized chunk of the world is and always has been composed of--Thompson is the guy for you.

Still, however, I'm always pleased to find qualities of suspense and puzzlement in a crime novel and one of my two favorite Thompson novels--the other is Pop. 1280--has just that. It's The Grifters.

Thompson published The Grifters in 1963, near the end of his great run as a novel writer. I couldn't find a single newspaper mention of it until 1984, when it was became one of the Thompson novels Black Lizard republished.

Six years later The Grifters was released as a film starring Anjelica Huston, John Cusack and Annette Bening. It was produced by Martin Scorsese and directed by Stephen Frears, an up and coming director who had already helmed the lauded films My Beautiful Laundrette, Prick up Your Ears and Dangerous Liaisons. (Is the last Renaissance noir?)

Huston, Cusack and Bening were all up-and-comers in a manner of speaking. Huston, 38 at the time of filming, was the daughter of the great sometime noir director John Huston (The Maltese Falcon, The Asphalt Jungle) and had won a supporting actor Oscar for her role in her father's gangster film Prizzi's Honor four years earlier.

Cusack, 23, was already a veteran of Eighties teen coming-of-age films and Bening, 31, made her breakthrough in this film. She received her first Oscar nomination (supporting) for this film, while Huston received her last (lead). Frears was nominated for best director and the screenwriter, noted crime writer Donald Westlake, was nominated for adapted screenplay.

Probably the film just missed a best picture nomination. (They really nominated Godfather Part III over this?) It still stand as one of the most lauded neo-noirs of its era. In the original noir era one might have seen, say, Joan Crawford, Tony Curtis and Gloria Grahame in the major roles.

I haven't seen the film in over thirty years but I certainly still remember some of the scenes. (Ugh, do I.) I had never read the book, however.

It's is about Roy Dillon, a 25-year-old short con grifter (as opposed to the grifter of the more complex long con, like running for President of the United States) who has been on his own since at age seventeen he left the single, "backwoods white trash" mother who negligently raised him.

At age thirteen Lilly Dillon married a thirty-year-old railroad worker, giving birth just shy of fourteen to Roy. Her husband died soon after and she eventually ended up in Baltimore as a B-girl and later went in for the bookie rackets. This has brought her out for a time to LA, coincidently when Roy is gravely ill with internal bleeding after a grift that went wrong resulted in his getting a baseball bat tap to his stomach.

Though Lilly, who had been a wayward adolescent mother and not much better as an adult, hasn't seen Roy in eight years, she takes him into her new place to recuperate. Roy also has a girlfriend, Moira Langtry, an attractive divorcee of, I think it was, thirty-one. Moira and Lilly can't stand each other (they see too much of themselves in each other) and Moira tries to set her son up with the nice young European immigrant day nurse, Carol Roberg, whom she has hired to help care for Roy.

Lilly, it seems, has developed a bit of a belated conscience about the shitty upbringing she provided for Roy, who has grown into a smart, handsome man, even if his ethics, like hers, are rather on the shady side. Moira, who has been living off a large sum of cash and occasionally granting other men her favors for a price, is none too scrupulously honest either. Of course she isn't happy about the prospect of Carol, nor is she pleased with the existence of Lilly. Nor does Lilly think much of Moira.

I have to stop here, just when the novel really gets interesting, because I don't want to spoil it for those who haven't read the book of seen the film. The last fifth of this short novel (about 55,000 words) is really headlong paced, with lots of suspense and classic noir twists and turns. It is indeed very much a noir novel, with copious irony in the just-missed opportunities and fatally spurned forks in the road. At heart it's a study of the two main characters, the mother and her son, both of them toiling in traps of their own devising.

Certainly neither one of them is a sympathetic individual, but neither are they entirely hateful either despite despicable things that they do. Both of them are driven by a desperate will to survive, but which of the two has the stronger will?

And then there's Moira, who is given some backstory too, though I was not as drawn to her character. Carol on the other hand is a genuinely "good girl" in the hard-boiled/noir tradition. Yet she is allowed quietly to fade from the narrative. (Indeed in the film she is largely eliminated altogether.)

This is not a sex and sleaze novel, though there is a torture scene of a woman involving a cigarette lighter and a bag of oranges that is particularly repellent (though it's not as bad as The Killer Inside Me). In many passages I actually found the book quite ruminative. They don't call Thompson Dimestore Dostoevsky for nothing. Very near the end the author offers some thoughts on men protecting women whether they like it or not, as you might say, which seem actually feminist, especially in today's environment.

Although Carol is a lesser character, there are some truly awful revelations concerning her that will stay with you, as will the book's ending. For a lot of people in the world life indeed is brutal, nasty and short. Thompson certainly catches that quality of what the poet Blake called endless night, what none other than Agatha Christie wrote about in her bleak mystery of that title concerning the activities of what you could well term a grifter, which she published four years after The Grifters.

It's what Thompson in the novel calls life on Uneasy Street. This is true noir in the black-and-white tradition, but just as timely and terrible as life is today:

For a fearful shadow lies constantly over the residents of Uneasy Street. It casts itself through the ostensibly friendly handshake, or the gorgeously wrapped package. It beams out from the baby's carriage, the barber's chair, the beauty parlor. Every neighbor is suspect, every outsider, everyone period; even one's husband or wife or sweetheart. There is no ease on Uneasy Street. The longer one's tenancy, the more untenable it becomes.

It's true too of even the whitest and loftiest of houses, at least when the grifters have taken up residence.

"Some marks fall for [the grift] repeatedly, without ever tipping"--great description of MAGA! As the man said, there's a sucker born every minute, mostly in this country apparently.

ReplyDeleteI really enjoyed this book for describing the life of the professional con artist in a suspenseful way. Considering we just elevated one to the White House, again, it seemed timely. I guess people feel that way about pols in general which I understand, but Trump really is a remarkable and exceptional career grifter whose bio should have been called The Art of the Steal. Thompson provides interesting insight into the minds of such people.

Delete