As

ECR Lorac and

Carol Carnac,

Edith Caroline Rivett (1894-1958) was one of the reliable "second-string" of British writers of the Golden Age generation for nearly three decades. Like

John Street,

Freeman Wills Crofts,

Christopher Bush and

Anthony Gilbert (

Lucy Beatrice Malleson), for example, she was published on both sides of the Atlantic (with some unfortunate gaps that make some of her titles very rare indeed today) and was a member of the

Detection Club.

Since her death nearly six decades ago, Rivett has become one of the most sought after vintage mystery writers by collectors, with only a few of her titles ever popping up in reprint edition, the most common being

Dover's

Murder by Matchlight. A few titles produced by

Ramble House also popped up for a time. Now I understand that the

British Library is reprinting the author's

Bats in the Belfry and

Fire in the Thatch, which likely is a prelude to others by her coming your way--major news in vintage mystery. Since Carol Rivett is an author I have read and researched (I was attempting to get all of her books reprinted), I thought I would discuss her on the blog.

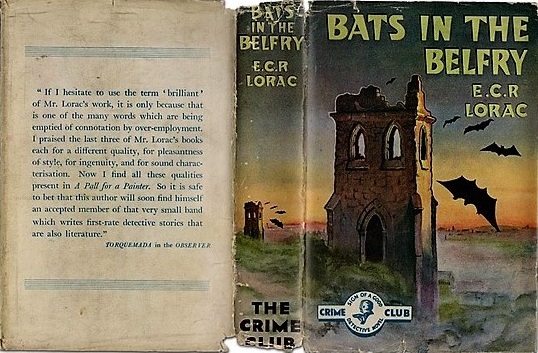

First off, I have to admit that I agree with those esteemed pure puzzlists

Jacques Barzun and

Wendell Hertig Taylor's criticism of

Bats in the Belfry in their

Catalogue of Crime. I don't want to quote their entry on the book, because of spoilers, but let's just say they nailed the book's issues as a puzzle in just three sentences. However, the book has, as

Martin Edwards has noted, a lot of the appealing milieu of classic crime fiction from the 1930s (who wouldn't love a place like "The Belfry"?), and for many modern fans of vintage mystery that may well be plenty. It's also, to be sure, a great title for a mystery novel. And the old Collins jacket is simply smashing--so superbly evocative.

After

Bats in the Belfry,

Fire in the Thatch is the very next entry in Barzun & Taylor's

COC, and B&T are much higher on this one, again I think justly. However, were I making recommendations for future reprints to the BL (which I'm not, unless this blog post counts), my choices would be, among the postwar Lorac titles,

Policemen in the Precinct (previously reprinted in the 1980s by Collins with a nice introduction by

HRF Keating),

Murder in the Mill Race and

Murder of a Martinet. Among the prewar titles which I have read it would be

Murder in Chelsea,

Murder in St. John's Wood,

A Pall for a Painter, and

Death of an Author.

I also would love to see

The Organ Speaks reprinted, as it is an extremely rare title that I have not read and one that

Dorothy L. Sayers, then on her own church musical kick with

The Nine Tailors, praised rather highly, though Martin does not like that one as much as

Bats in the Belfry.

The early, prewar Carnacs also are fantastically rare, and it would be nice to see those reprinted too. Among the Carnacs that I have read my favorite is

The Double Turn. (Another one I like a lot is

It's Her Own Funeral.) Reviewer

Anthony Boucher was of the opinion that Rivett's best work dated from the Fifties, and she certainly had some good titles in that decade. However, whatever I think--or Martin, or Anthony Boucher, or Barzun & Taylor--ideally all of Rivett's detective novels (71 of them, and one that was never published, according to Martin) should be reprinted, so that the vintage mystery fans out there can judge for themselves.

|

| Paddington Station |

Surprisingly little has been written, to my knowledge, about Carol Rivett, as she was known. Even

Martin Edwards' The Golden Age of Murder, for example, gives Rivett and her work little attention, particularly in light of the extensive coverage afforded many other writers. In the book there is much more about GDH and Margaret Cole, for example, who were much less consistent (and committed) detection writers than Rivett, one of the consummate British mystery genre professionals of the era.

To be sure, the Coles led rather more interesting lives, both politically and personally, at least as far as we know.

But just what in fact

do we know about Carol Rivett?

Carol Rivett was born Edith Caroline Rivett in Hendon, London in 1894 to Harry and Beatrice (Foot) Rivett. Harry Rivett was a commercial traveler in silver goods (I'm reminded of the line in

Bertolt Brecht's unfinished novel

The Business Affairs of Mr. Julius Caesar, as translated by

Charles Osborne, "

How often do I have to remind you lot that we waged war in Spain; we didn't do business. Now he wants to march back into town like a commercial traveller in silver goods!").

Harry's wife, Beatrice, was the daughter of Edward Smith Foot, who worked first as a railway cashier for the

Great Western Railway (of

Paddington Station fame, bringing to mind

John Rhode's The Paddington Mystery and

The Murders in Praed Street) and later as a rate collector in the district of Marylebone.

Carol Rivett wrote about London rather well, as Martin notes, because she knew London rather well indeed. Her parents were lifelong Londoners, Harry and Beatrice both having grown up in Marylebone, where Harry's father, John Charles Rivett, owned a china and glass shop, and Beatrice's grandfather, Edward Smith Foot, Sr. served for 35 years as Superintendent of the

Marylebone Baths and Wash-houses.

|

at the baths

a dirty job, but someone had to do it |

John Charles Rivett moved to London in the 1850s, but he was born in the village of Carlton, Cambridgeshire, the son of John Rivett, a farm laborer originally from Hundon, Suffolk. John Rivett's father, Aaron Rivett, had originally trekked with his family about ten miles from Hundon to Carlton. Although the family was a humble one, Aaron Rivett did rate a page in the October 4, 1851 edition of the

Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, on account of his great longevity:

The hill country in this neighbourhood has long been remarkable for the long period of existence allotted to its inhabitants. A year or two since a woman lived to the age of 102 in this village [Carlton], and at the present time a man named Aaron Rivett is 92, and bids fair to arrive at 100. He has one daughter aged 70, living at Twickenham, and so many great-grandchildren that eh finds it difficult to reckon them up. Rivett has been a moderate man all of his life, fond of his glass, but never to excess. It is said that he has not been so well since he tried to do altogether without it.

Alas, Aaron died two years after the publciation of this article, still a half-dozen years shy of a century. He was probably a grandson of a Moses Rivett of Hundon, who died in there in 1753, but there the lineage fades into obscurity. In the Rivett's case, as in so many others, the move from country to city was a hugely significant event for one branch of the family.

The Foots--or the Feet, recalling the Proudfoots/Proudfeet debate in Tolkien's saga--also moved from county to city, though their roots were in trade, not in the land per se. The father of Edward Foot, Sr., Joseph Button Foot, was a saddler in the small Cotswold town of Cricklade, Wiltshire, who after his marriage moved with his wife to the market town of Cirencester, Gloucestershire, where in 1817 he tragically drowned at the age of 26 while bathing in the River Churn, a tributary of the Thames. The family returned to Cricklade, where daughter Frances Foot wed John Hopkins, a tailor, and son John Foot became a draper's assistant, but Edward headed for London, again markedly changing family fortunes.

For much of the 1840s Edward worked as a saddler in London, but in 1849 he and his family moved into the newly-constructed Marylebone Baths and Wash-houses. There Edward would serve as superintendent until his death in 1885 and his wife, Frances (a cousin, I believe), as matron until her death in 1875, when she was succeeded by Beatrice's Aunt Annie.

|

The Rivetts, in the 1890s, probably

shortly before departure for Australia

Gladys upper left, Maud upper right, Carol seated

(photo from "An Account of a Sea Journey") |

Beatrice Foot's 1890 marriage with Harry Rivett produced three daughters, but the union was destined to prove tragically short-lived, with Harry a decade later dying at sea from tuberculosis on a months-long voyage from Australia to England.

This voyage was detailed over six decades later in "

An Account of a Sea Journey," a memorable short memoir by Carol Rivett's sister

Maud Rivett Howson, republished with addenda by her nephew-in-law

George Howson, in

Contrebis, the journal of the

Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society. (See

here.)

The Rivett family originally set out from London for Australia in 1898 aboard the

Oroya, arriving on December 9 in Melbourne, where Harry's older brother, William Charles Rivett, who had been employed in England as a clerk in a wool brokerage business, had previously settled.

Sadly, Harry did not get better in the warm Australian climate, and a little over a year later the family booked a slow passage back to England, the terminally ill Harry hoping to die at sea.

Harry, Beatrice and their three young daughters, Gladys, Maud and Carol, left Australia on March 2, 1900 for England on the

Illawarra, "

an iron-built, three-masted, full-rigged sailing ship,"

commencing a sea-journey of 15,000 miles and five months around

southern Africa that Harry would not survive. In telling this story Maud

Howson speculated that future generations might have difficult

believing that "

an ordinary family, in the opening months of the twentieth century," could make such a journey

with

only the wind as their motive power; with only paraffin for their

lighting; with no heating for the small cabins and saloon in which they

had to shelter from tempestuous weather; with only small signal flags as

a means of communication with passing vessels, who alone could report

their news or condition to a land-based port.

|

| Oroya |

|

| Illawarra |

It is a fascinating short account that I urge you to read. Concerning the baby of the family, Carol, who was about six years old at the time, Maude mentions that despite the supervision of their mother and a merchant navy cadet "

who was absolutely devoted to her," the young child "

took the opportunity of climbing on the taffrail" when the crew were signalling another ship as the

Illawarra neared South Africa:

Mother, happening to look around, just saved her from going overboard, when the ship began to move again. We elder ones all climbed on the taffrail at times, though we were forbidden to: it must have been about 3 ft or 3 ft 6 ins from the deck and a most insecure perch.

|

| off St. Helena |

On June 6 the ship reached St. Helena, once remote home to the exiled

Emperor Napoleon and at the time home to some 2000 Boers, prisoners of the then ongoing conflict with Great Britain. Down to L5 in cash and with her husband near death, Beatrice stayed on board with her children, though she did mail the letters home that were later consulted by Maude when she wrote her travel memoir.

Three days after the ship left St. Helena on June 9, Harry died and was interned in the ocean, 55 miles from Ascension Island. The crew, Maude notes mordantly, was rather glad to see Harry shuffle off this mortal coil:

[T]hey had regarded my poor father as a man with death in his face, ever since he had boarded the ship at Melbourne; and, according to the superstitions of their calling, they regarded him as the bearer of the ill-luck which had beset the voyage. When he had been safely buried, the crew said that the luck would change; there appears to have been something in it [as we had] good weather and no serious setbacks in the North Atlantic.

|

| wide sargasso sea |

Not long after passing the island, the Illawarra crossed into the North Atlantic, giving the crew occasion to prank Maude and her sisters, who

were all hoodwinked by the officer holding up a thread across binoculars at the noon sight, so that we could say we had seen the Line when we crossed it. I think I was suspicious, but Carol said that she boasted for years that she had seen the Equator.

The same month the ship passed into the seemingly boundless Sargasso Sea:

[T]he surface was like a meadow, so thick it was with golden-green seaweeds. Of course, all the children were violently excited, and acquired (or made) hooks and lines of every kind to fish up the seaweeds from the water and land them on the deck of the ship; again, why we never went overboard in our excitement, I cannot imagine.

The soon-stinking mess that accumulated on the ship deck was met with something less than pleasure by the crew and officers, however:

"We got into more trouble...over this business than over anything else on the whole voyage. Luckily, we did not know what bad language meant, but we were often threatened with a rope's end." (Here I am reminded of the title of one of Carol Rivett's detective novels,

Rope's End, Rogue's End.)

|

| underground at Baker Street |

Their home in London, after they finally arrived in the City on August 3, 1900, was 13 Marlborough Place, St. John's Wood, where resided in Victorian patriarchal majesty Beatrice's father, as well as his unmarried children, sons Edward and Herbert and daughters Chloe, Janet and Annie. With widowed Beatrice and her three daughters joining the household, there were ten individuals all told, along with one, no doubt very busy, house-servant.

Maude and her sisters found their arrival in London bewildering indeed:

However, my mother was a Londoner, born and bred, and off we went by rail to Fenchurch Street and thence by the old sulphurous Underground Railway to Baker Street. There, Mother's last pennies had given out and we all packed into a hansom-cab, knowing that there would be someone to pay the fare when we arrived.

It was streaming with rain and heavily overcast when we reached "home." I can remember the crowd of aunts and uncles who greeted us, but only very faintly. My clearest recollection of that night as we all sat around the supper table is Grandpa saying "It's dark; turn on the light": somebody pulled the string of the 'by-pass' light on the fixture of an old-fashioned incandescent gas burner.

I was nearly blinded by the sudden illumination and stared in amazement: it seemed miraculous after the dim oil lamps of Illawarra

. I did not know that such an indoor light existed anyway on sea or land. This must have been what Mother meant by "home."

As part of her father's household, Beatrice was put on the government payroll (joining her sister Chloe) as

an assistant to her borough rate collector father, while another of Beatrice's sisters in

the household, Annie, worked as a draper's assistant.

|

Athabasca Hall

where Maud Rivett lived when a teacher

at the University of Alberta |

The Foot family may seem

rather conventional and "bourgeois," if you will, but one of their

number, Beatrice's brother Herbert, in 1903 was an actuary who was

elected to the

Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures

and Commerce, which puts him in company with

William Hogarth, Benjamin Franklin, Adam Smith, Charles Dickens and

Karl Marx.

(There's even-handedness for you.)

Another of Beatrice's sisters, Edith

Maud Foot, married

James Edward Forty, a freemason and the beloved headmaster, from 1893 to 1926, of

Hull Grammar School. They sometimes were visited by Carol Rivett.

Beatrice's middle daughter, Maud, went into education herself, obtaining a B.Sc. degree in botany the

Royal College of Science, Imperial College London and teaching for a short time at the

University of Alberta before in 1922 marrying

John Howson,

headmaster of Bicester Grammar School in Oxfordshire. A native

Lancastrian, Howson upon his retirement in 1941 returned to Lancashire

with Maud, where the couple was active in local community affairs. This

move greatly influenced Carol Rivett and her later detective fiction,

as we will see.

|

| The Rivett domicile (left half of central building) |

The oldest Rivett sister, Gladys, appears to have become a private nurse. The youngest, Carol, was given a good education at

South Hampstead High School, one of the first girls' day schools in London, and the

Central School of Arts and Crafts, established in 1896 as an outgrowth of the Arts and Crafts movement.

As she did not publish her first detective novel,

The Murder on the Burrows, until 1931, when she was 37 years old, I am not clear how she supported herself up to that point, but her mother Beatrice-- with whom she lived at the now rather posh and pricey 71 Carlton Hill, St. John's Wood up to the outbreak of the Second World War--seems to have made Carol her primary heir when she died in 1943. There seems to have been some money in the family that made its way to Beatrice and Carol.

|

| Thurlestone Hotel |

During part of the war Carol Rivett was evacuated from London to the

Thurlestone Hotel, a luxury establishment in Devon still in operation today. There Carol shared space with students from

Ravenscroft (this possibly the boys' prep school at Yelverton, Devon, which was requisitioned as an officers' mess in 1941), causing her to remark in a letter (dated 8 November 1940) that "

the combination of boarding school and luxury hotel is even more fatuous than the establishments separately!" (See

here.)

After the war, Carol moved away from the world of "fatuous" luxury hotels to an isolated locale in rural Lancashire (where her sister Maud and Maud's husband John already had gone), having fallen in love with the countryside there.

Although many of Carol's prewar detective novels were set in London, her postwar books more often take place in rural England, frequently in the north country. Several novels are specifically set in Lancashire's lovely Lune Valley, along the River Lune.

Indeed, one of her later detective novels is named

Crook O'Lune (

Shepherd's Crook in the US), after a picturesque turning in the river that was painted by

JMW Turner. It is a sequel of sorts to her novels

Fell Murder,

The Theft of the Iron Dogs and

Still Waters.

|

"Crook Of Lune, Looking towards Hornby Castle" (c. 1816-1818)

by Joseph Mallord William Turner |

By the 1950s Carol Rivett lived at an adored stone cottage named "Newbanks" in the Lancashire parish of Aughton. The house itself served as the setting for her novel

Crook O'Lune. Sadly, however, Rivett died at the age of 64 in 1958. She left an unfinished novel behind her (and one unpublished one, apparently completed years earlier). An extremely prolific author, Carol produced 71 detective novels in 27 years. (There were two mainstream novels as well, published under her own name.)

In 1958 alone there appeared, under her two pseudonyms,

Death in Triplicate, Murder on a Monument and

Long Shadows, followed in 1959 by two posthumously published novels,

Death of a Lady Killer and

Dishonour among Thieves (as stated above what was evidently intended to be her third 1959 novel was left unfinished).

Had Carol Rivett been granted the same more generous spans of life as

Agatha Christie (1890-1976) or

Gladys Mitchell (1901-1983), say, and lived until the late 1970s, she might well have published well over 100 detective novels, rivaling

John Street as perhaps the most prolific of true Golden Age detective novelists. It's strange to think that she might still have been publishing into the Thatcher Era.

Carol's sister Maud survived her by a decade and both sisters are

buried, along with eldest sister Gladys, on the grounds at

St.

Savior's Church, Aughton. Although I do not believe, as some notable authorities

of the day urged, that Carol Rivett quite belongs in quite the same rank with

Christie, Mitchell,

Dorothy L. Sayers,

Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, Georgette Heyer and

Christianna Brand,

she is nevertheless most definitely one of the more notable figures in the second tier

of Golden Age British mystery, and I hope that soon enough all of her books will

be back in print, for fans of vintage mystery to enjoy.

Coming soon: a discussion of the matter of Carol Rivett's pen names, and a review of one of her novels.