Seventy-two-year-old Sidney Toler was less than seven months away from death when shooting on The Trap--his last Charlie Chan film for poverty row Hollywood film studio Monogram Pictures--wrapped up in August 1946. The film would premier on November 30, by which time the actor was bedridden with terminal cancer. He died on February 12, 1947, about ten weeks shy of his seventy-third birthday.

The Trap was the fifth Chan film Toler made for Monogram in 1946, following The Red Dragon, Dark Alibi, Shadows over Chinatown and Dangerous Money. Rather like actor Bruce Willis in more recent times, Toler soldiered on despite precipitously declining health, though by the time of the filming of The Trap he was said to be constantly exhausted and in considerable pain, making the ongoing effort challenging. After The Trap he finally could not go on with it anymore, though the Chan film series would be revived yet one more time with another caucasian actor, Roland Winters, playing the Chinese detective for six more films between 1947 and 1949.

In the late 1950s Chan would be played on television by J. Carroll Naish in a year-long series, The New Adventures of Charlie Chan. There was even a brief early Seventies Charlie Chan cartoon series, with the actor who back in the Thirties played Chan's number one son, Keye Luke (now in his sixties) at least getting to voice Charlie Chan. (Jodie Foster voiced one of the daughters!)

English actor Peter Sellers parodied Charlie Chan (or more accurately Caucasian actors portrayals of him) in the 1976 satirical mystery comedy Murder by Death. The character's last film appearance was five years later in Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen, which starred another Caucasian English actor, Peter Ustinov, who was coming off his success playing Belgian Hercule Poirot in Death on the Nile (1978), in the title part.

For nearly forty-five years now there have been no new screen Chans, but the world has not gone Chanless. Like the Forties Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes films, the Charlie Chan films from the 1930s and 1940s have maintained a loyal following among mystery film fans, despite decades of criticism of the flicks for having Caucasian men--Swede Warner Oland and Americans Sidney Toler and Roland Winters--playing Chan.

Sidney Toler took over the Chan franchise in 1938 after Warner Oland--who starting in 1931 played Chan in sixteen films (four of which are lost)--died in 1937 at the age of 58. Beginning with Charlie Chan in Honolulu, which premiered in January 1939, Toler made eleven Chan films for Twentieth-Century Fox before the studio canceled the series after Castle in the Desert, which premiered in February 1942.

|

| If looks could kill: a fiendish face in Dangerous Money |

Toler, a long time character actor in films, enjoyed his three years finally playing lead and he shopped around the Chan series to other studios, only getting a taker in 1943 with Monogram, a so-called poverty row (i.e., el cheapo) studio. For Monogram he would live to make eleven more Chan films, beginning with Charlie Chan in the Secret Service, which premiered in February 1944. All told he would spent about three years doing Chan at Fox and another three years doing Chan at Monogram, making 22 films which constitute a rich legacy for mystery fans, even if the Monogram flicks admittedly have much cheaper production values and some undoubted rough patches.

In six of the Monogram Chans, Charlie's primary "assistant" offspring was number three son Tommy, played by Benson Fong, who was in his late twenties when essaying the role. In Charlie Chan in the Secret Service he shares assisting duties (admittedly dubiously) with number two daughter Iris (Marianne Quon), while in the films Black Magic and The Jade Mask he is displaced respectively by another Chan daughter (number three?), Frances Chan (played by, how about that, Frances Chan), and number four son Eddie, played by Edwin Luke, real life younger brother of Keye Luke.

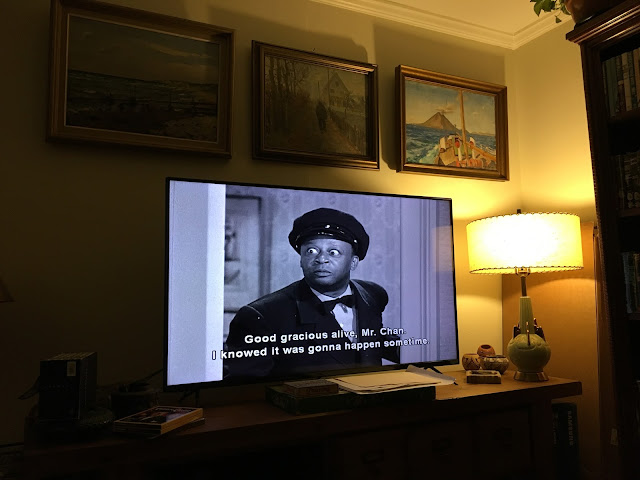

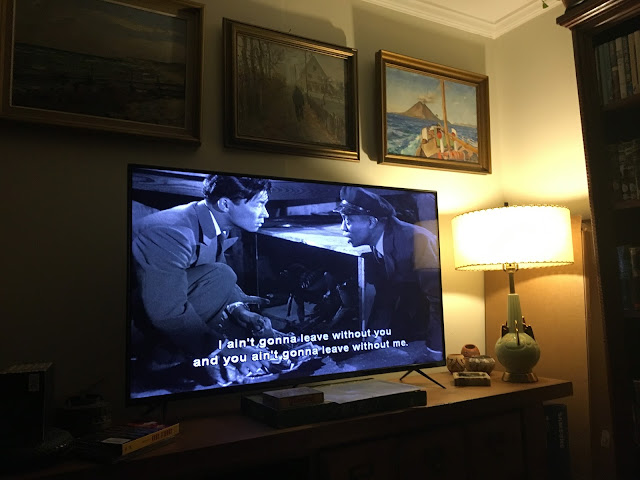

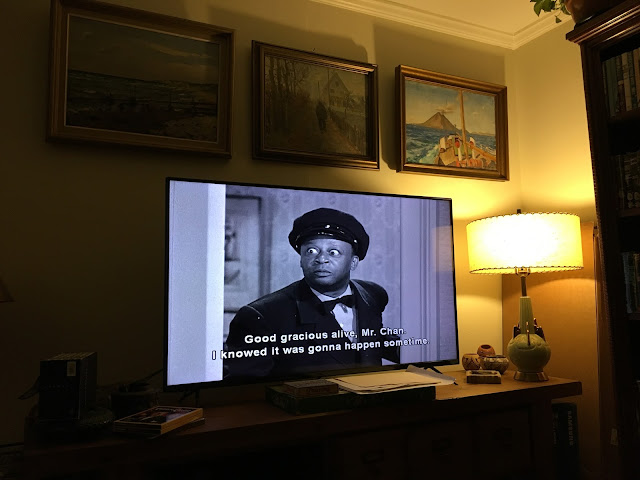

This suggests to me that Monogram was a little doubtful of Benson Fong's thespianic abilities, but Fong actually improved over his next four appearances and developed a good rapport with Charlie's other "assistant", introduced in the Monogram films: chauffeur Birmingham Brown, played by brilliant black comic actor Mantan Moreland. Like Stepin Fetchit and Willie Best and other black actors of the Thirties and Forties, Moreland was confined to comical servant roles, but somehow he triumphantly bursts out of stereotype and really comes off as a true individual, and not at all dumb. He was genuinely popular with black audiences and it's said that on movie marquees in black neighborhoods his name was placed above Toler's. In the worst of the Monogram Chan films he actually supplies the most entertaining moments.

The eleven Monogram Charlie Chan films (rated by me on a ten poverty row scale as a B-mystery junkie) are:

1944

Charlie Chan in the Secret Service (february) 7

The Chinese Cat (may) 6

Black Magic (august) 4

1945

The Jade Mask (january) 6

The Scarlet Clue (may) 5

The Shanghai Cobra (September) 5

1946

The Red Dragon (february) 3

Dark Alibi (may) 8

Shadows over Chinatown (june) 4

Dangerous Money (october) 6.5

The Trap (november) 6.5

Five films in 1946 suggests a really accelerated production schedule and I suspect they tried to get in the last two films while Toler was still able to do them. There's some indication of haste to the last two Toler Chans, which have often had detractors in modern times. Maybe it's the contrarian in me, but as you can see these are two of my favorites in the Monogram series, after what seems to me its clear summit, Dark Alibi, and its debut outing, Secret Service.

|

| Not a case of thousands, quite, but there is no shortage of suspects in The Trap. |

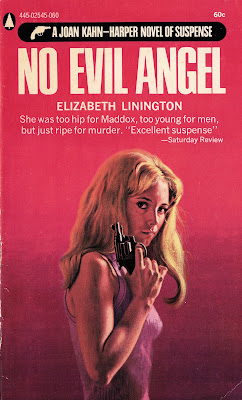

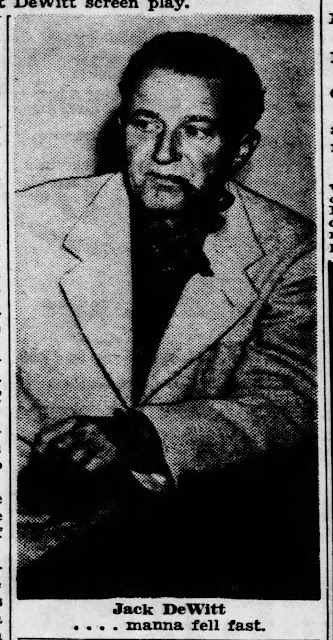

The last two films in the series, Dangerous Money and The Trap, are unique in having a credited scripter named Miriam Kissinger, about whom no information is given on imdb, She has no other credits to her name. Presumably she was Miriam Kissinger of Santa Barbara, California, who was married to then neophyte screenwriter Jack DeWitt. Possibly the Chan scripts actually were written by him, using his wife's name for some reason. DeWitt, the son of Methodist minister Jackson Dewitt, was born in Morrilton, Arkansas in 1900. I have no idea what this man did over the next three decades, but in 1930 he was living in Council Bluffs, Iowa and working as crime reporter for the Daily Nonpareil.

DeWitt also served as a Justice of the Peace. One of the cases that came up before him concerned a teenager named Herbert Rosenthal, a delivery boy and son of an immigrant Lithuanian Jewish grocer who in 1932 was charged with the offense of driving his car 45 miles an hour on the wrong side of the street. (I don't know whether he was making a delivery at the time--maybe he worked for Domino's Pizza and they had a guarantee.)

The Nonpareil reported that at the bench the youngster faced the JP confidently, pertly informing him: "I can't be sent to jail because of my age, and if you fine me my Dad will have to pay it." Justice DeWitt had young Rosenthal copy a sentence he had written down, then told him to go home and write that sentence 3000 times and hand it in to the sheriff within three days. The sentence was "Delivery boys drive dangerously." DeWitt retained his sample of the boy's handwriting to make sure that the 3000 sentences he turned in were from his own hand.

At least Rosenthal put his devil-may-care recklessness to good use, like Tom Cruise in Top Gun. Rosenthal family history records that Herbert, who would become a colonel in the US Air Force during the Second World War "lived large" and was "a daredevil that loved thrills and chills--physical challenges, fast cars and fast boats and motorcycles, the tang of danger. He liked to smoke and drink and party all night. On two occasions he walked away unharmed after his Air Force jet crash-landed. He won accolades in fistfights, wrestling matches, sharpshooting competitions and motorbike races."

|

| Miriam Kissinger |

Rosenthal was appointed US Air Attache in Athens, Greece in the Sixties and was decorated for maneuvering the US Ambassador through a dangerous coup d'etat. Back in the US in 1969 he assigned Lt. Joseph Caudle to escort Miss Colorado, one of the princesses in the DC Cherry Blossom Festival. Caudle took the opportunity to criticize the ongoing omission of "Negroes as princesses and escorts," for which statement he was relieved of his duty as an escort by an Air Force major. Rosenthal, however, declared that no disciplinary action would be taken against Caudle. The DC Board of Trade promised that efforts would be made to achieve racial diversity.

Sounds like Colonel Rosenthal had his head on straight and his heart in the right place. Maybe those 3000 sentences Jack DeWitt made him write had a good effect.

Another case DeWitt heard in 1932 was a suit brought by a man, John P. Kelley, against American President Herbert Hoover, demanding eighteen cents, the current market price for a typical chicken, because the president as a candidate in 1928 had promised Americans a chicken in every pot and he, Kelley, never got one.

Jack DeWitt married in Council Bluffs, but his wife died from a heart ailment after only a few years of marriage. (There's one for the crime writers.)

DeWitt decided to try to succeed as a freelance writer and moved to Bandon, Oregon. Over the rest of the decade he produced scores of true crime articles for pulp magazines. In 1936 he married again, this time to Miriam Kissinger, a radio dramatist in Lincoln, Nebraska. In the late Thirties the couple moved to Santa Barbara, California where Miriam had the couple's first child and Jack began writing for the film industry.

In 1941 he produced his first filmed script for International Lady, a spy thriller starring George Brent, Basil Rathbone and Ilona Massey as the lady. The same year he published a crime novel, Murder on Shark Island, which was optioned but not actually made into a film. The next year he wrote the script for Beyond the Blue Horizon, a South Seas melodrama starring Dorothy Lamour.

Both these films were from major studios. However, DeWitt's next official screen credit is not for four additional years, with the script for Don Ricardo Returns (1946), a Zorro-esque drama for PRC, the cheapest of the cheapo studios. After this DeWitt seems to have scripted almost exclusively for Poverty Row and later for television, except that he had an odd late in life resurgence after writing the script for the modern Western classic A Man Called Horse (1970), starring Richard Harris. He died eleven years later at the age of eighty.

Surprisingly given his background in true crime and early work in mystery, DeWitt's film and television scripts on the whole were not for crime and mystery movies. Probably his next most famous film after Horse is the adventure flick Bomba the Jungle Boy (1949). But it is certainly plausible that he and not Miriam Kissinger wrote the script for the two last Toler Chan films, Dangerous Money and The Trap.

Yet in that case why would not DeWitt have used his own name, rather than his wife's, if she had nothing to do with the scripts? It is hard to believe he would have been embarrassed to acknowledge publicly having written Chan films for Monogram, when the same year he wrote, under his own name, the script for a PRC adventure film. It seems to me more likely that the spouses might have collaborated on the scripts, Miriam having background as a radio dramatist and actress at a Lincoln, Nebraska radio station.

In any event the two Chan films scripted by either or both of the spouses strike me as some of the best of the series. Flaws in the films probably have to do more with cuts made to the scripts and scenes edited out of the film, rather than the scripts themselves.

In Dangerous Money, Charlie Chan is on a Pacific liner on his way to--well, now I forget where (Australia?), but there is to be a one night stopover in American Samoa. All the Monogram Chans ran slightly over an hour and in this one the first forty minutes take place on the ocean liner, making it essentially a shipboard mystery film. It's filmed pretty convincingly, though there are lots of nighttime fog scenes, which, aside from being atmospheric, were cheap to shoot. The few rear screen daytime scenes to suggest that the cast is really on a ship as opposed to stage sets are actually fairly well done though.

|

| On the deck PT Burke bores the minister and his wife and the professor and his entourage |

|

Chan questions lovers Gloria Warren, daughter of a renowned art collector,

and George Brace, the ship's purser |

The plot concerns the machinations of a gang of counterfeiters, who during the late war stashed their hot money somewhere on Samoa and now with the cessation of hostilities want to get it back again--and they will kill to do so. When the film opens an attempt is made on the life of the American treasury agent investigating the matter (dependable Tristram Coffin) and when he suggests to Charlie that they go back to his room for safety, the Great Detective brilliantly suggests that they instead go sit in the dining room where they can scope out the suspects. The evening entertainment is a knife thrower and, sure enough, the treasury agent shortly ends up dead from a knife thrown into his back by someone on the deck. It wasn't the knife thrower though (or was it).

The knife thrower, by the way, is played by John Harmon, who played the "crusty lighthouse keeper"--Is there any other kind?--in The Monster of Piedras Blancas, one of those rubber suit monster films from the 1950s (don't know whether this one is radioactive, but I love monsters and lighthouses). Harmon's last film was 1979's Microwave Massacre, which likely is every bit as bad as it sounds. Same year he did Malibu High, which is apparently considered a Seventies sexploitation classic. Old dude really hung in there! Like most of the actors in Dangerous Money, however, Harmon is another solid contributor.

|

| Chan learns someone is trying to kill treasury agent Scott Pearson |

|

| knife thrower Freddie Kirk (John Harmon) provides entertainment |

|

| Stabbed in the back! |

Charlie investigates on ship, mostly by observing or eavesdropping upon other people. For their part, Chan's assistants, his No. 2 son Jimmy (Victor Sen Young) and his chauffeur Chattanooga Brown (Willie Best, subbing for Mantan Moreland's infinitely superior Birmingham Brown), bumble around as well. The weakness of Dangerous Money lies primarily in the poor comic relief bits with Jimmy and Chattanooga, which aren't really integrated for most of the film with Chan's investigation.

Jimmy wants to gets everyone's fingerprints so there's a bit with that and then the pair follow the trail of a cook's assistant who has been flashing a big wad of bills. Ultimately this does go somewhere, though strictly accidentally. There are also a couple scenes where the two bumblers use walkie-talkies, taking on the respective codes names Chop Suey and Pork Chop. Guess which is which?

|

| Number two son has a new toy |

|

| Chattanooga lays it on the line. |

Benson Fong, who as mentioned had appeared in six Monogram Chan films as number three son Tommy Chan, had actually developed a pretty good rapport with Mantan Moreland's Birmingham Brown by this time and I missed them both in DM. Never does the film explain why these characters are absent, or even why Chan needed any assistants with him on the cruise in the first place (though Tommy does send his pop a telegram).

The last time we saw Jimmy, in 1942's Castle in the Desert, he was on leave from the army. Although he was only a year older than Benson Fong (thirty at the time of this film), Sen Yung looked older than that and the role of enthusiastic comical juvenile doesn't sit quite as well with Jimmy in 1946 as it had in 1942. Sen Yung is still good, however, though he has no chemistry with Willie Best.

In his two appearances in the series, Willie Best unfortunately is pretty cringeworthy. Mantan Moreland was able to transcend the "frightened negro" routine, but Best, for whatever reason, doesn't. I remember him as being good in the Bob Hope fright comedy The Ghost Breakers, but that film probably gave him a better role to work with. It's the biggest flaw of this script that it gives Best nothing.

On the other hand, the mystery plot is enjoyable. There's a lot going on and most of it, red herrings and all, is adequately disposed of. There is some evidence, however, that some cuts were made to the film, leaving some things unexplained. There are surviving stills from the film that show things that you don't see in the actual final cut.

At the start of one scene we see Jimmy and Chattanooga with the bound and gagged native guard of the ichthyology museum and we never actually see the encounter that led to the affray which must have taken place. There's also the unsolved mystery of the turtle and the strap-on flashlight. (Nothing naughty, I assure you; see film.)

I suspect sometimes that when people complain that these mysteries are confusing, it's due to edits. This film was edited down to about an hour and five minutes, when it probably was something more like and hour and twenty originally. Incredibly, the last murder takes place at the hour mark, with only five minutes left to wrap up!

On the plus side, though, the performances are quite good for this sort of film, on the whole. Standouts are Rick Vallin as Tao Erickson, a smooth, if not oleaginous, Samoan trader (I think he's supposed to be a half-caste--half Samoan, half-Swedish or something--he looks like Fox News' smarmy and insincere Jesse Waters here); roly-poly Dick Elliot as PT Burke (Barnum?), a fast-talking, cigar-waving textiles executive from Dixie with all sorts of opinions about the murder (I will always think of him as Mayberry's mayor on The Andy Griffith Show); Gloria Warren as female "juvenile" love interest Rona Simmons (a personable actress who had a very brief film career and died about two years ago); and Leslie Denison as scolding missionary Reverend Dr. Whipple, who with his equally censorious wife disapproves of all the sketchy shipboard goings-on around them.

|

| Freddie Kirk and PT Barnes |

|

| PT Burke gets a surprise |

|

noted absent-minded ichthyologist Professor Martin,

his handsome secretary and his pretty younger wife |

|

| the Reverend and Mrs. Whipple, walking in harmony as always |

Denison, a reliable native British actor who I'm not sure had any really standout role though his face looked very familiar to me as a watcher of B-films (he looks a lot like Henry Daniell), is probably best known today for providing testimony in the murder of actor David Bacon in 1943. Supposedly a closeted homosexual in a lavender marriage with cabaret singer Greta Keller, Bacon had a trysting pad in a Laurel Canyon duplex shared with Denison, who lived in the upper half of the building. Reading between the lines, Bacon may have been killed by a short blond pickup from the merchant marine.

Definitely not a scenario you will find in a Charlie Chan film! Did Denison play on both sides as well? I have no idea. He seems to have married later in life, and divorced.

At its resolution Dangerous Money does have one very cute and ahead of its time twist, which, unfortunately, I can't give here. And the last scene, in which Jimmy literally provokes his pop into strangling him, is an amusing one, because we fans have been seeing that coming for a long time.

|

| Will Charlie finally commit his own murder? |

People have said that Toler began to feel sick during the filming of Dangerous Money, but his performance seems up to the Monogram par. He even has a two minute dance sequence with Tao Erickson's lovely wife Laura, played by Egyptian actress Amira Moustafa, whose credited film work consisted of this role and Queen of the Amazons from the same year, where she played the titular queen Amazon, Zita. This film gets a 3.6 on imdb, so must really be something. Amira dropped out of film work right after it. Yet she's perfectly fine in the Chan film.

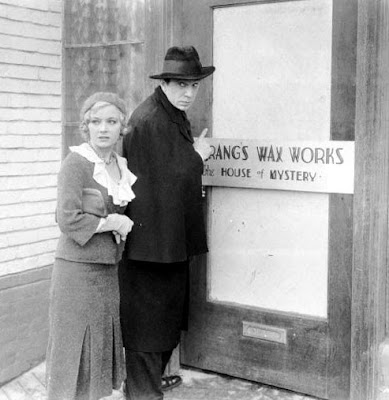

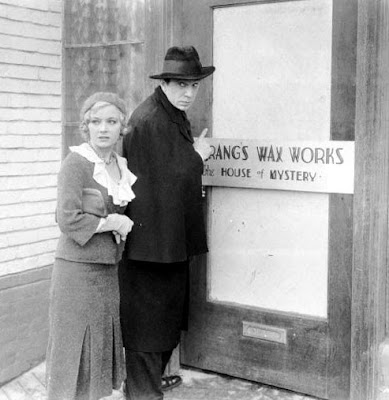

|

Daddy issues

Viva Tattersall in Whispering Shadow with her "father"

Bela Lugosi (who was eight years younger than

her future husband Sidney Toler) |

Truth be told, I think Toler had been showing his age and declining health from the start of the Monogram series in 1944, when he was 69 years old. Just two years earlier in the final Fox Chan film, Castle in the Desert, he looked noticeably younger and more energetic.

Toler's first wife, Vivian Marston, died at age 65 in October 1943 and a month later Toler married Vera "Viva" Tattersall, a beautiful blonde native English woman who was 24 years younger than he.

A former actress probably best known today for playing Bela Lugosi's daughter in the crime serial The Whispering Shadow (1933), she had been Toler's mistress, I suspect, for years. When he died in 1947, Viva told newspapers that her husband of less than four years had never really recovered from an operation in 1943.

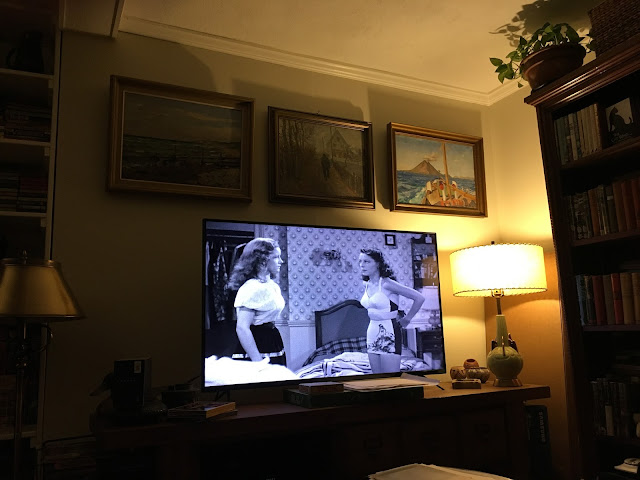

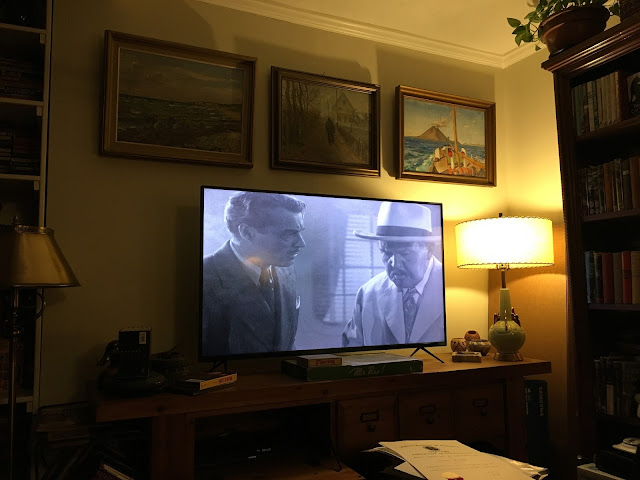

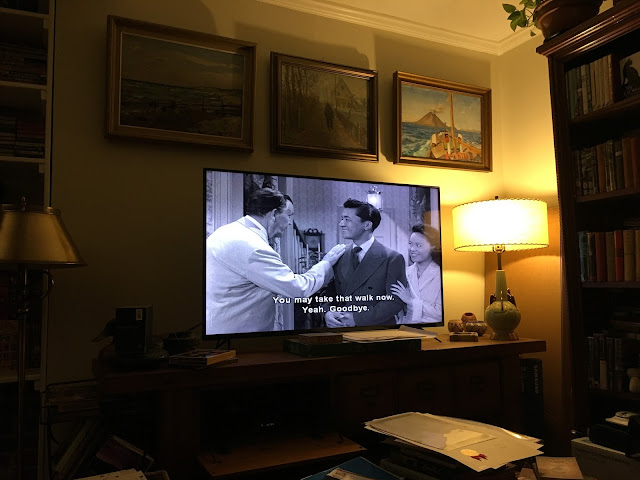

By the time of the filming of The Trap, Toler's energy level had noticeably declined. Much of the screen time in the film is handed over to the supporting players, including son Jimmy and Birmingham Brown (Mantan Moreland is back, thankfully) and a hunky young (or youngish) motorcycle cop who improbably heads the murder investigation.

|

| Kirk Alyn playing a different sort of lawman |

The cop is played by thirty-five-year-old Kirk Alyn (aka John Feggo), who a couple of years later would become the first man to play Superman on film. Alyn is sixth-billed, but it's probably his most substantial part in a regular film, his Superman and other leading performances all being in serials.

Most of the film roles of Kirk Alyn--who started his entertainment career not long out of high school in the late 1920s as a stage choirboy in New York and moved to LA around 1940, marrying there a few years later--went uncredited. Yet prior to The Trap he was in fact credited in 1943's The Man from the Rio Grande, Overland Mail Robbery and Pistol Packin' Mama and 1944's Forty Thieves, Call of the Rockies and The Girl Who Dared, the latter a decent adaptation of Medora Field's mystery novel Blood on Her Shoe, reprinted by Coachwhip with an introduction by me.

Despite all this, in August 1947, LA Times drama columnist William Schallert reported that

Kirk Alyn, husband of [singer-actress] Virginia O'Brien, seems all set for a movie career. It's a new venture for him, though he modeled for physical culture propaganda for a long time, being a strapping sort of chap.

Monogram has signed him for the leading juvenile part in "The Trap," and that was because he was observed by James S. Burkett, producer of his Charlie Chan whodunit, while screening as John the Baptist in A Voice in the Wilderness, one of Cathedral Films' 16mm Biblical subjects.

Engagement in "The Trap" will be only a break-in, because it is believed his career will proceed a lot further.

I've never seen reference anywhere else to Alyn as a physique model, but as an old man he liked to tell the story about how when he auditioned for Superman that they asked him to take off his shirt and then his pants and he was like, "Wait a minute....I thought this only happened to women." When playing John the Baptist he runs about with a fake black beard in a short, sleeveless tunic like a peplum film extra, showing off some well-developed arms and long legs, though his voice is ludicrously dubbed in a booming bass voice.

In The Trap Alyn stands out a lot, towering over the rest of the cast in his motorcycle cop outfit (complete with jodhpurs). There is even considerable focus, it struck me anyway, on Alyn's, um, ample bum, shall we say. I guess the producer indeed was impressed with his physique, likewise the director and photographer.

|

| Reynolds doing justice to his jodhpurs |

|

| Reynolds revs up his engine |

|

| Reynolds investigates. (I think he's looking for a secret passage.) |

|

| okay, this butt shot was completely gratuitous |

|

| Reynolds confronts Rick |

|

| Jimmy comes out of the closet |

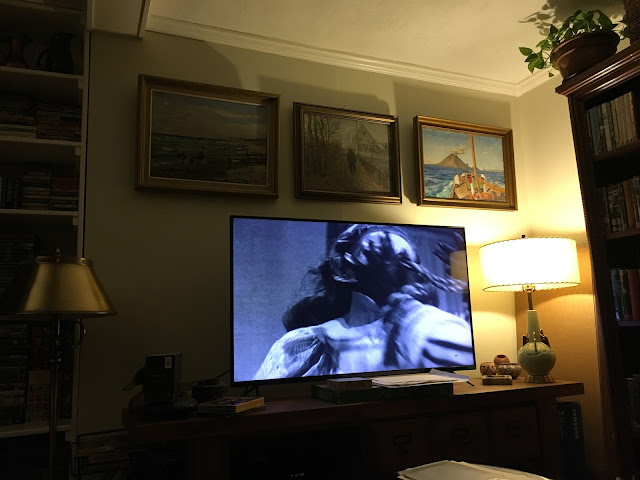

But, fear not, in this Chan installment there are also a lot of pretty showgirls, who get some time in between murders to run about in bathing suits on the beach with their flabby, pale middle-aged male bosses, which is probably a realistic enough depiction of Hollywood, then and now.

Sergeant Reynolds never dons a bathing suit throughout the film, only ever appearing in his cop clothes, but then they say women love a man in uniform. Ruby, one of the showgirls, certainly does!

|

| Another dead body is discovered |

|

| A subtle hint that Winifred and Rick are an item. Winifred's role was edited down to the bone. |

|

| Even after carousing on the beach, Clementine is still nervous |

Malibu Beach is an hour or so down the coast from where Jack DeWitt and Miriam Kissinger lived in Santa Barbara. In fact the working title of the film was Murder at Malibu Beach. It opens with a shot of our strapping motorcycle cop standing at the porch of Malibu Beach Real Estate (a very recognizable actual place) and observing a car speeding down the highway. He hops on his bike and stops the car, to find that it's filled with a troupe of show people heading for a Malibu Beach mansion they've rented for a few weeks to enjoy some fun and sun. Off they go on their merry way, getting let off with a warning, but we'll be seeing police sergeant Reynolds again.

|

| Ruby gets a good look at a Malibu native |

|

| the building where the movie's opening film was filmed (see above) |

When the show troupe arrives at the mansion they encounter forbidding housekeeper Mrs. Weebles, who seems like something right out of Rebecca, maybe Mrs. Danvers' older sister, as she disapprovingly sneers about "show people." She's played by Minerva Urecal, a fun character actress who specialized in this type. There's actually a scene where, seemingly frightened, she throws her apron over head and runs away, something I had read in books but never actually seen in a film.

Some people have complained about the large cast of show people, and indeed it is, so I will helpfully list them all here for you:

|

sinister housekeeper Mrs. Weebles with her toasting fork,

like she's ready to roast sinners |

|

| Hearing a scream Mrs. Weebles throws her apron over her head and runs off in panic. |

|

Women from left to right:

Winifred, Clementine, Ruby, Adelaide, Mrs. Thorne, San Toy, Madge Mudge

Men from left to right:

Rick Daniels, George Brandt, Sgt. Reynolds, Cole King |

The Women (Nine):

Adelaide (Tanis Chandler)--the very French one, oui, oui! She's in love with the troupe physiotherapist (see below). The native French Tanis Chandler appeared in the mystery film Lured, with Lucille Ball and Boris Karloff, and she played "waitress" in The Big Sleep

|

| Adelaide professed her love for George. Pork pies? She means pigsties, get it? |

Marcia (Anne Nagel)--the biatch who you know will get killed off. She knows secrets of Adelaide and the troupe's "maestro" and knows too much for her own good all round. Marcia--or Mar-cee-a as the maestro calls her (I don't know whether this is a nod to the character's pretentiousness or whether the actor simply didn't know how to pronounce Marcia)--is not in the film very long, I'll just say, but she makes an impression with her all round hatefulness.

In real life Anne Nagel married closeted gay actor Ross Alexander, who committed suicide in 1937 after a year of marriage to her. Nagel was thirty by the time of The Trap and thus older than the other girls. She plays her witchypoo character with conviction.

|

| Marcia looks daggers at Adelaide |

|

| Marcia looks daggers at Lois |

Clementine (Rita Quigley)--the screamer who you want to see killed off but it never happens damn it. Clementine is always frightened, not to mention terribly racist, and she screams at everything. I've seen Rita Quigley in another film, Whispering Footsteps, and she played a perfectly normal rational adult human being there, so she's not at fault here, she was playing the character as was wanted.

Oddly enough in Whispering Footsteps it was her real life younger sister, former child star Juanita Quigley (aka "Baby Jane," I kid you not) who did all the screaming. In my view goofy Clemmie adds zest to the film, though a lot of people just hate her.

|

| Clementine has a premonition of doom |

|

It's a Chinese trick!

Clementine goes all racist on San Toy |

Ruby (Helen Gerald)--the flirt. Ruby spends the film coming on to Sergeant Reynolds and can you really blame the girl? Born in 1926, it appears that Helen Gerald is still around today, maybe still pining for Kirk Alyn. |

| Well, hello sergeant! |

|

| Sergeant Reynolds is modest. |

Lois (Jan Bryant)--the ingenue forced to do Marcia's bidding who actually gets bumped off first. Actress Jan Bryant may still be around today too; little is known of her.

Winifred (Bettie Best)--the nonentity who probably should have been cut from the film. Yet another actress with a brief career, Bettie Best is given very little to do here. She is supposed to be the publicist's girlfriend, but not much is made of that accept as related to the publicist. The actress is fine, just needed an actual scene to herself.

San Toy (Barbara Jean Wong)--the "little Chinese girl." She's very spunky and spirited and brings Charlie into the case and looks to become Jimmy's girlfriend at the end. Barbara Jean Wong is best known for playing Arbedella Jones, daughter of Amos Jones on the hugely popular radio series Amos and Andy. She was a child actress known as the Chinese Shirley Temple. She's pretty and very fluent in English--a good catch for Jimmy.

Madge Mudge (I kid you not) (Margaret Brayton)--the troupe's deadpan masseuse. Over her career Brayton played a lot of nurses, secretaries, policewomen, manicurists, so this role was right in line.

Mrs. Thorne (Lois Austin)--wardrobe mistress and house mother.

The Men (three)

Cole King (Cole Porter?) (Howard Negley)--the troupe's leader, or maestro as they call him. Negley capably played lots cops, tough guys, bad buys. I thought he was only so-so here though.

George Brandt (Walden Boyle)--the troupe's physiotherapist and Adelaide's boyfriend.

Rick Daniels (Larry Blake)--the troupe's excitable publicist. His acting career on film and television ran from 1937 to 1979. He has some fisticuffs with Sergeant Reynolds in this film and later told his son disliked Kirk Alyn during filming. Jealous?

When you throw in the housekeeper, Jimmy, and Birmingham and Charlie Chan himself, you have sixteen people running around this house (one of them the murderer) and, frankly, I was impressed that the camera managed literally to keep track of them all. Really the photography of the film is quite good and the beach shots (on a real beach) and studio shots (the house and backyard) are well-integrated. The murder of Lois is quite effectively staged, for example, as are the scenes in the cellar.

By the way, the set decorator, thirty-four-year-old Raymond Boltz, was on only his fifth film here, but he did a good job with the house. (He had previously done Dangerous Money.) His last work was in the early Seventies when he decorated the sets for the Mary Tyler Moore Show's first three seasons, which I think it pretty cool. I swear to God some of the stuff in The Trap looks like it ended up in Mary's and Rhoda's apartments.

|

| Charlie has an audience |

|

| Birmingham tries to keep count of the cast. |

|

| Poor Lois gets done in. |

|

| in the cellar |

|

Jimmy falls down the coal chute and make a discovery.

Thankfully no blackface joke was made here. |

|

| San Toy meanced |

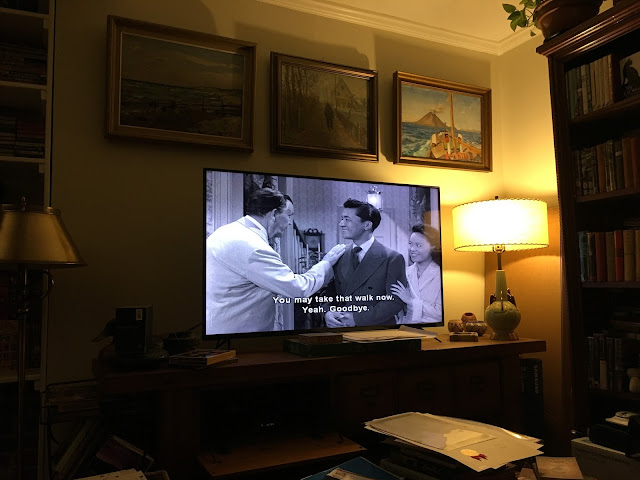

For some reason Chan is living near Malibu (LA?) in this one, along with Birmingham, who actually does get to chauffeur this time, and Jimmy. No mention is made of the wife and family back home in Honolulu. When showgirl Lois is strangled to death at the rental house in Malibu and Clementine starts screeching that murdering with a silk cord is a "Chinese trick" and looking meaningfully at San Toy, the latter decides to call Jimmy, who has been bragging about his detective work to her. He will defend his country woman she cries! So Charlie gets involved in yet another case, albeit nearly halfway into the short film.

Truthfully Toler doesn't get nearly as much screen time as he normally did and he does seem more tired (there's a scene with Kirk Alyn where he stands with his one hand on the fender of a car as if to support himself), but he's still enjoyable to watch. Mantan Moreland gets the fading shot, but Charlie has a nice moment with his son at the end. With the case solved, he's eager just to get out of the house and get home to bed--kind of a poignant metaphor for what Toler was going through in real life.

The solution is reached very quickly after the hour mark and a car chase and the motive is pretty wooly, I'll allow, but I enjoyed the fact that this is a genuine detective story rather than a crime thriller. In the end, though, Charlie admits he has to resort to a trap to catch the killer (hence the title). I didn't find this a bad sendoff for Toler at all. To the contrary I thought it one of the better films in the Monogram Chan line. Again it would have been nice had it been able to run another ten minutes or so.

|

| chasing a murderer |

|

| Crash! |

|

| Charlie says goodbye to his son in Toler's last few seconds in the long-running series. |

The Trap was directed by Howard Bretherton, who seems to have done little work in mysteries, though a year earlier he did direct the mystery serial Who's Guilty? Dangerous Money was directed by Terry Morse who helmed the undistinguished Shadows over Chinatown, the previous Chan feature, as well as Fog Island (1945), a cheapo B mystery fan favorite. However he's best known for directing the Raymond Burr scenes in the classic Fifties atomic creature feature Godzilla King of the Monsters.

So that's my take on the last two Toler Monogram Chans. I'm glad Toler stuck with the series as long as he could, because in my view they ended on a mostly delightful note, at least by Monogram standards.

|

| murder reenactment with Jimmy playing corpse and Charlie murderer |

|

| Moreland's best lines in the film |