Presently there came a wheezy whistle and the little train panted laboriously into the station. Its three grimy non-corridor coaches looked of 1905 vintage, the only spot of color being the vivid "British Railways" medallion recently painted exactly in the centre of each. It seemed surprising that anyone should have wanted to claim them. The compartment which Edward got into was bare and narrow, with broken window straps and a slashed seat. A cloud of dust rose from the faded upholstery as he sat down. Framed under the narrow luggage rack opposite him was a streaky photograph of Southend Pier in which all the men wore straw boaters. Edward felt rather at home with it.

*****

"I like your railway line--it's got personality."

"We call it the cuckoo line....I'm afraid it has more personality than passengers."

--The Cuckoo Line Affair (1953), by Andrew Garve

A placid train journey through the country turns into a horror excursion when a passenger spies a woman being throttled by a man....Wait, isn't this the 1957 Miss Marple detective novel 4.50 from Paddington, by the inimitable Agatha Christie (filmed in 1961 as Murder She Said, the first of the Margaret Rutherford Miss Marple mystery flicks)?

Why, no, in this case it's The Cuckoo Line Affair, by Andrew Garve, a detective novel which preceded Christie's novel by four years.

During the four decades that fell between 1938 and 1978, Paul Winterton published forty crime novels, thirty of them under his Andrew Garve pseudonym. The Cuckoo Line Affair was his sixth Garve. The first six Garves appeared in a flurry of foul play between 1950 and 1953. (Another crime novel would follow later in the late summer of 1953, bringing the total to seven.)

Additionally in this period Winterton published his final Roger Bax crime novel, A Grave Case of Murder, in 1951, making the total eight novels in four years. It was the author's busiest period as a crime writer, along with 1956-1961, when he published a dozen crime novels in six years, eight of them Garves and four of them opuses by "Paul Somers." In the final phase of Winterton's career, from 1962 to 1978, he published fourteen crime novels, all of the Garves, mostly at the rate of one per year. (After 1972, he slowed down to one every two years, until he stopped altogether at the age of seventy in 1978.)

Technically Winterton, like Elizabeth Ferrars and Christianna Brand, just qualifies as a Golden Age crime writer in my view, because he published his first two crime novels, both of them "Roger Bax" international thrillers in the early Eric Ambler style, in 1938 and 1940 respectively (Death Beneath Jerusalem and Red Escapade). He was very busy the next few years covering the war in his "day job" as a journalist, but then between 1947 and 1949 he published three more Roger Bax crime novels, an interesting trio of books, and left journalism altogether.

The first of these Baxes, Disposing of Henry, is a quite exceptionally nasty inverted mystery in the style of Francis Iles. (Henry's murder is surely one of the cruelest in the business; obviously during World War Two Garve realized man's capacity for evil knew no bounds.) The second one, Blueprint for Murder, is another inverted, though it is more in the workmanlike style of Freeman Wills Crofts. (It's also, I believe, Garve's longest crime novel, at about 100,000 words.) Finally, there is Came the Dawn, a flight-and-pursuit thriller set in the Soviet Union. It was filmed under the title Never Let Me Go, starring Clark Gable and Gene Tierney (as a Russian).

All of these novels received good reviews, but in 1950 Winterton created a new pen name, Andrew Garve, and by 1952 Garve had completely superseded Bax. Apparently Garve decided he didn't want to keep up two pen names. Confused? Let me list these early books:

Paul Somerton Crime Novels, 1938-1954

Death Beneath Jerusalem (1938) (Bax) (international thriller)

Red Escapade (1940) (Bax) (ditto)

Disposing of Henry (1947) (Bax) (inverted murder novel)

Blueprint for Murder/The Trouble with Murder (1948) (Bax) (ditto)

Came the Dawn/Two if by Sea (1949) (Bax) (international thriller)

No Tears for Hilda (1950) (Garve) (mystery, detection/suspense)

No Mask for Murder (1950) (Garve) (inverted murder novel)

A Press of Suspects/Byline for Murder (1951) (Garve) (ditto)

A Grave Case of Murder (1951) (Bax) (detective novel)

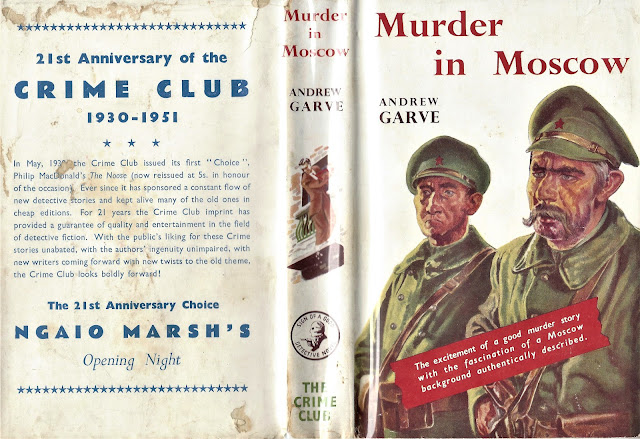

Murder in Moscow/Murder Through the Looking Glass (1951) (Garve) (detective novel)

A Hole in the Ground (1952) (Garve) (suspense)

The Cuckoo Line Affair (1953) (Garve) (mystery, detection/suspense)

Death and the Sky Above (1953) (Garve) (mystery, suspense/detection)

The Riddle of Samson (1954) (Garve) (mystery, suspense/detection)

Out of these fourteen crime novels, really only two, in my view, are straight-up, simon-pure detective stories: Murder in Moscow and A Grave Case of Murder, both of which appeared in 1951. Earlier in his career Garve/Bax gravitated toward inverted murder tales and international thrillers, but by the early Fifties he was shifting more to suspense stories with detection. Of these latter hybrids from this period, the most satisficing, as far as detection goes, is The Cuckoo Line Affair.

The title of the novel refers to the popular nickname for a rather decrepit, provincial, one-track railway line in East Anglia, Garve's favored stomping ground in his domestic mysteries. It would seem that the author borrowed the idea of his Cuckoo Line from England's real-life Cuckoo Line, closed since the Sixties, which was located in East Sussex. Part of that line was single track. The Cuckoo Trail, a fourteen mile footpath, follows the old one-line track by Hellingly Station, now a private residence. I include some pictures of the station because I think it captures the ambience of Garve's charming novel.

|

| Hellingly Station on the Cuckoo Line, several years after the line closed in 1965 The previous year it appeared in the British crime film Smokescreen |

The key train station in Garve's novel is located at the village of Steepleford. I assume this is fictional, although the late English folk singer Roy Harris (not to be confused with the American composer) recorded a rendition of "Steepleford Town" in 1975 and there is a town of Stapleford in Nottinghamshire, about thirty miles north of Leicester, where Garve was born.

In Garve's Steepleford at Lavender Cottage (there's a Lilac Cottage in the title of a John Rhode detective novel) resides sixty-year-old widower Edward Latimer and his unmarried adult daughter, Gertrude, aka "Trudie." Living separately are Edward's two sons, the elder a somewhat stolid lawyer in a nearby town named Quentin, aka "Quent," and the younger a London financial journalist and fledgling mystery writer named Hugh (no nickname this time). Hugh writes his mysteries with considerable help with his pretty and plucky fiancée, Cynthia, secretary to an MP.

Father Edward's great moment in life occurred two decades earlier when he himself, then an "underpaid schoolmaster," was elected to parliament, for a single term, on the Liberal ticket. After that Edward, over forty and with a wife and three children to support, had to make ends meet as a freelance journalist, which he has managed pretty well and contentedly, if somewhat eccentrically.

|

| Hellington Station on the Cuckoo Trail today |

Hugh, having taken Cynthia over on the Cuckoo Line to meet his father and Trudie for the first time, describes his father warmly as follows:

....he had that stab at Parliament and got in and was as happy as a sandboy, meeting people and helping them with their little problems and trying to put things right generally. He's a great reformer, you know, in his quiet way, and the kindest man alive--if everyone were like him the world wouldn't be a bad place to live in.

I go into detail here in part to emphasize the importance in the novel of Edward as a sympathetic, more rounded character (more on this shortly), but also because if you know something of Garve's life it's obvious he substantially based Edward on his own father, George Ernest Winterton, a Leicestershire schoolmaster turned journalist with the Daily Herald who served briefly in parliament as a member of the Independent Labour Party during 1929-31.

Ernest was also a Methodist (I believe, though another source claims he was a Baptist) and a most zealous temperance advocate, a trait which Garve embodies in the novel in another, far less attractive character. I think it's safe to conclude that, much as he may have admired his father in general, Garve did not share Ernest's intense religiosity-- although during the Thirties he did share something of his father's leftwing politics.

Garve--after graduating from the London School of Economics with a B.Sc. degree at the age of twenty in 1928 and spending nine months on a travelling scholarship, probably in 1930, on a farming commune in Ukraine--ran unsuccessfully for parliament in 1931 and 1935 as a Labour candidate in conservative constituencies in southern England. In Mitcham, a south London borough, he managed in 1935 to cut the Conservative majority from 25,000 to 9000, according to John Harrison, so he must have had some appeal. Perhaps he was the Beto O'Rourke of Mitcham.

|

| Andrew Garve presumably in his late Thirties, back when he was briefly known as Roger Bax |

Newspapers described the young, bespectacled financial journalist as an "excellent speaker" with a "keen interest in politics." He garnered sympathy as well when, on the eve of polling, his wife of five years, Margaret Helen Colegrave, expired from injuries suffered in a car accident in which the couple had been involved in Selsdon a month earlier.

Garve got off relatively lightly from the wreck and continued campaigning with his arm in a sling, but his wife was taken immediately to Purley Hospital and never left there alive. Garve remarried in 1936, to Audrey Kathleen Hopkin.

Although as mentioned above Andrew Garve grew up in Leicester, he was living with Audrey in the south London borough of Croydon in 1939. His parents, then resided in the small market town of Spilsby in Lincolnshire. Later they moved south to Chichester in West Sussex, where Ernest died in 1942 and his wife, Garve's mother, passed away the next year.

I'm guessing that Garve rode the East Sussex Cuckoo Line at some point when en route to visiting his parents and that he became familiar with the saltings and fens of the East Midlands/East Anglia during visits to Spilsby.

Garve obviously was a writer who never wasted a scrap of "material." He even made the police sergeant in Murderer's Fen, reviewed here, a grief-stricken widower whose young wife was killed in a car accident by a reckless driver, leaving him with a toddler daughter. (Garve had four children, but I don't know how they were distributed between wives.)

The character of Hugh Latimer in The Cuckoo Line Affair, a financial journalist moonlighting as a mystery writer whose hobby is sailing, clearly is modeled closely after the author himself. There's also a character with the surname of Hopkin, the same as that of his second wife.

|

| much is made of boats as well as trains in The Cuckoo Line Affair |

Like the Cuckoo Line itself, the saltings play a huge role in The Cuckoo Line Affair. Hugh has a small boat, Water Baby, which he shows off to Cynthia early in the novel, and it later plays a great role in the book.

Indeed, this is probably the saltingest English mystery since Henry Wade's Mist on the Saltings (1933). The physical descriptions and a later climactic scene in the book are marvelous.

But what the hell is the book about, you must be asking at this point, where is the mystery? Well, Garve takes these nice people, the Latimers, and this nice village, Steepleford, and plunges everything into turmoil.

An attractive young woman, alone with Edward in a compartment of the Cuckoo Line, accuses him of physically assaulting her. Worse yet, two eyewitnesses, a man actually on the train, and a signalman looking at it, say they saw Edward assaulting the young woman. The signalman dramatically claims that Edward was actually forcing her head out the window.

It looks certain that Edward will be taken into custody, despite the fact that he is highly respectable and insists that the young woman threw herself upon him (there are those independent witnesses, you see), when the woman suddenly drops the charge. This seems a happy ending, but Edward now finds himself shunned by the village. (Villages do love to shun.) And then, worse yet, the woman, a Londoner named Helen Fairlie, is shortly afterward found dead from manual strangulation, at a lonely spot on the saltings where Edward had made an appointment to meet her!

Edward, who is subject to sunstroke and blackouts, has no memory of having actually met Miss Fairlie, but is he going mad, or is he a calculating sex fiend and murderer...or, perhaps, the victim of a wicked frame-up? But why? And who? And how?

It's up to the Latimer boys to save their Dad, ably assisted by plucky Cynthia. (Trudie is an oddly negligible character, disparaged by Hugh and Quentin for her general dullness in the book's only sour note.)

Fortunately Hugh and Cynthia, being mystery writers, have considerable imagination!

This is a terrific mystery, highly praised by, among others, highbrows Jacques Barzun and Eudora Welty and mystery writers Frances Crane and Rex Stout ("This one is a doozy," the latter individual.) It is also a notable example of Garve's approach to the crime fiction form. The suspense element is heightened considerably from traditional detection, because one of the main characters, one whom we come to like very much, is actually arrested and charged with the murder.

The reader, in other words, is not just idly enjoying a chess problem, peopled by pieces of wood or stone; they are vicariously involved in a suspenseful situation, feeling anxiety for the players. Yet there is a quite cleverly plotted problem here, with some very clever twists which you have to watch out for. It's a model of post-WW2, midcentury mystery, possibly even a Mystery You Have to Read. (I will think that over, but I already have picked one by Garve, as you will recall, Murder in Moscow.)

Some today have deemed the book that dread word "dated," but I think that's part of its charm, rather. It's pretty to think that a nice English family can work together to save one of their members in trouble and solve a murder along the way. All you need is grit and a bit of brains, it seems!

There are also some fun meta moments as Hugh and Cynthia discuss the craft of mystery writing. I think I will devote a short separate blog piece to this sometime. One thing I will mention here is that Hugh grouses about being contractually obligated to write 80,000 word books. By my count Cuckoo Line is about 75,000 words. Garve, having become a big name in mystery, would soon liberate himself from this requirement, penning books as short as 50,000 words. Personally I like Garve's short works, but I think the 75,000 word books work quite well too. People like blogger Jason Half who want more flesh on their novels probably should look at the earlier books of this length. (On the other hand, Blueprint for Murder at around 100,000 words feels far too long to me.)

|

| Miss Marple saw it herself in the film version Margaret Rutherford in Murder She Said (1961) |

Two decades later, over the years 1973-75, Eudora Welty corresponded with her great author friend, American crime writer Ross Macdonald, about a series Macdonald was editing, Ross Macdonald Selects Great Stories of Suspense. Welty wanted to help with his selection of four novels for the series, but she kept deciding that her suggestions weren't quite "good enough" in retrospect. She reported having the "fondest memories" of The Cuckoo Line Affair, but she still didn't think it quite measured up to the series standard.

What finally made the cut? Ross Macdonald's own The Far Side of the Dollar (modestly he had wanted instead to include Beast in View, by his wife, Margaret Millar, but the publisher deemed that book too literary); Dick Francis' Enquiry; Kenneth Fearing's The Big Clock; and Agatha Christie's What Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw!, aka:

4.50 from Paddington

Them's the breaks! Dame Agatha always wins. But surely everyone here has read that already? Give the Garve a try, why don't you?