"I told him it was a prodigal daughter case."

"God, I despise you Archer! You're a dirty little sees-all hears-all tells-all monkey, aren't you? What difference does it make to you what people do?"

--The Way Some People Die (1951), by Ross Macdonald

Okay, dear readers, are you Team Chandler or Team Ross? No, I'm not talking about the cast of the Nineties TV series Friends, of course, but the hard-boiled crime writers Raymond Chandler (1888-1959) and Ross Macdonald (1915-1983), two of the three hosts, along with Dashiell Hammett, in the hard-boiled triumvirate.

After 'prenticing by writing short crime fiction in the pulps, Raymond Chandler--something of a querulous, alcoholic, middle-aged failure--finally in 1939, when he was 51 years old, published The Big Sleep, one of the cornerstones of crime fiction. He would publish a total of seven Philip Marlowe hard-boiled crime novels between 1939 and 1958. Aside from The Big Sleep, these are Farewell, My Lovely (1940), The High Window (1942), The Lady in the Lake (1943), The Little Sister (1949), The Long Goodbye (1953) and Playback (1958), the latter deemed a disappointing coda to a major body of bloodwork.

It's a small output for a professional crime writer, but Chandler notoriously had great trouble thinking out plots for his novels. Three of them, Sleep, Lovely and Lake, fuse, with varying success, earlier short stories to build the novel structure, while Playback was based on an unproduced film screenplay. Chandler did scripting work in Hollywood, notably working, between 1944 and 1951, on screenplays for the crime films Double Indemnity (Oscar screenplay nomination), The Unseen, The Blue Dahlia (Oscar screenplay nomination), and Strangers on a Train.

Chandler was successful by the standards of mystery publishing in the day, but he felt underappreciated, both by the critics and the public. And it's true that the literary world, including academia at the time, tended to adopt a condescending attitude toward crime writing. Chandler was often very bitter and on lonely nights at his typewriter had a tendency to indulge his sense of snark at the expense of myriad people, places and things, not the least of which were other crime writers. (Were Chandler around today, he probably would have been banned from Twitter numerous times. I can see easily Chandler as an internet curmudgeon, griping about wokeness and cancellation.)

One of the crime writers whom Chandler lambasted was that young up-and-comer Ross Macdonald, a Canadian-American in his thirties who came of an academic background. (He eventually received his PhD in English in 1952, at the age of 37.) After publishing four non-series 'prentice works of crime fiction under his actual name, Kenneth Millar, as Ross Macdonald he published his first Lew Archer hard-boiled detective novel, The Moving Target, in April 1949, to acclaim from crime fiction reviewers.

The influential Anthony Boucher, just starting his two decade long stint reviewing crime fiction at the New York Times, was rhapsodic, proclaiming that the author of The Moving Target stood head and shoulders over his competitors in the hard-boiled field as a weaver of words and observer of people. When critic James Sandoe wrote Raymond Chandler about The Moving Target he called it an "astonishing book," but added that it was a "pure pastiche" of Chandler and "fundamentally phony," though "it disguised the fact better than I could possibly have anticipated."

Chandler himself was not amused, pronouncing the book affected--he famously derided Macdonald's description of a deteriorated car as being "acned with rust"--and synthetic in its emotions. The author, he declared, was just another one of the fancy pants intellectuals, "literary eunuchs" who imitate others and show off with surface cleverness because they themselves "feel nothing."

It could not have soothed Chandler's feelings that when his own first novel in six years, The Little Sister, appeared later that year, Anthony Boucher essentially panned it, writing that the novel presented the unpleasant "spectacle of a prose writer of high attainments wasting his talents in a pretentious attempt to make bricks without straw--or much clay, either."

When Boucher chose selected the best crime novels of 1949, he excluded The Little Sister and included The Moving Target, writing that Macdonald had returned the "much-abused hard-boiled detective story to its original Hammett high level." The suggestion that Macdonald--not Chandler--might be Hammett's rightful heir must have been especially galling to Chandler, who definitely read Boucher's columns in the New York Times Book Review. Chandler not long afterward referred to Boucher as a "pipsqueak," though this was in connection with another matter.

When Macdonald's second Lew Archer detective novel, The Drowning Pool, appeared in 1950, Chandler attacked it in private correspondence, just as he had The Moving Target, calling much of it "pure parody" of his own writing, though he allowed: "The man has ability. He could be a good writer."

Again Macdonald won general critical praise, however, and his next book, The Way Some People Die, received an absolute rave from Boucher, who pronounced it "the best novel in the tough tradition that I've read since Farewell, My Lovely...and possibly since The Maltese Falcon." (The ellipses were Boucher's own.) If the latter claim would true, this meant that Die was better than anything Chandler himself had yet written. Macdonald, not Chandler, would be the real heir to Hammett. This Macdonald book likewise made Boucher's best of the year list.

Chandler would rebound in Anthony Boucher's estimation in 1953 with the publication of The Long Goodbye, which many consider Chandler's magnum opus. The novel would win an Edgar from the Mystery Writers of Americas for best novel of the year, a distinction which no RM novel ever achieved. Macdonald himself would, with The Doomsters (1958) and particularly The Galton Case (1959), move away from from Chandler and the hard-boiled style, writing another dozen or so books about multi-generational family dysfunction, with Archer now acting as a sort of soft-boiled family therapist. Macdonald himself thought that he had achieved something new and important with this shift and many critics agreed, though some damned Macdonald's later books as tedious psychological naval-gazing. The comment was frequently made that Macdonald wrote the same book and over.

Whatever one thinks of the later books, however, the view seems to have crystallized fairly firmly that the early Macdonalds are, as Chandler himself thought. overly imitative of Chandler, that with them Macdonald had not found his true self as an author--the real Ross, as it were.

Maybe not, but I think several of the early books are damn good anyway!

I have reread The Moving Target and found it rather better than I recalled, but in this post I want to talk one of RM biographer Tom Nolan's favorites among the early novels, The Way Some People Die. It really is superb.

*******

Anyway, in Die Archer is hired by a highly proper and traditional widow, Mrs. Samuel Lawrence, the widow of a doctor, to find her beautiful twenty-four-year-old daughter, Galley (Galatea), whom she has not heard from for more than a couple of months.

Right away from this first chapter, indeed the first paragraph, or really the first sentence, the writing grabs you:

The house was in Santa Monica on a cross street between the boulevards, within earshot of the coast highway and rifleshot of the sea. The street was the kind that people had once been proud to live on, but in the last few years it had lost its claim to pride. The houses had too many stories, too few widows, not enough paint....Even the palms that lined the street looked as if they had seen their best days and were starting to lose their hair.

Within "rifleshot of the sea"--love it! Even in his tougher days, Archer is something of a soft touch, as he observes: "The house didn't look as it it had money in it, or ever would again. I went in anyway, because I'd liked the woman's voice on the telephone."

The interior of the house--Victorian, of course--is packed with furniture: "If the lady had come down in the world, she'd brought a lot down with her." Mrs. Lawrence serves tea which tastes "like a clear dark dripping from the past." This last line is a good example of the RM use of alliterative similes and metaphors. His writing often has a distinct poetic cadence--"clear dark dripping from the past"--that really roils off the tongue. As he sits at tea, Archer observes: "My grandmother came back with it, in crisp black funeral silks, and I had to look out of the window to dispel her."

All of this so far could have come out of a classic British mystery (although the keen writing would not have been so common), but when Archer begins investigating Galley's disappearance, he finds himself emerging from the genteel past into the tawdry present, a treacherous world of double and triple cross crosses and multiplying violent murders.

Macdonald is equally adept at portraying this latter world of depravity, with its gangsters and floozies and junkies. And the junkies! RW's biographer Tom Nolan notes the influence on The Way Some People Die of Nelson Algren's recent published novel The Man with the Golden Arm, which won the first National Book Award in 1950. There's an uncommon sober grittiness to sections of Die that really sends it to the head of the hard-boiled class. If Chandler feared being superseded by Macdonald, those fears would have been amplified by Die and its successor in the Archer series, The Ivory Grin (1952). Perhaps it was these works that made Chandler step up his game with The Long Goodbye.

*******

|

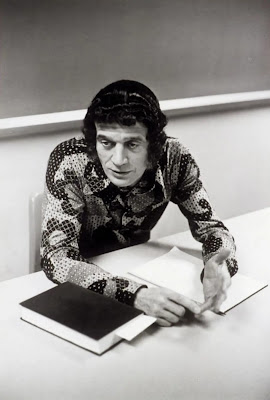

| Ross Macdonald |

When Chandler's comments to James Sandoe disparaging RM were published around 1960, after Chandler's death, RM was furious and his perception of Chandler was forever colored by it. However, even before that time RM had tired of the comparisons of himself to Chandler, as if he were nothing more than an imitator. "I hear on all sides, though I refrain from reading Chandler myself, that Chandler's last book [The Little Sister] wasn't that good, which leaves a bit of a vacuum in the field," RM bluntly wrote his publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, whom Chandler had left when he published The Little Sister with Houghton, Mifflin.

Knopf replied equally that "Chandler's last was just as well written as ever, but it exposed clearly his weakness and satisfied me that there were quite sound reasons why we had never sold him as he thought he ought to be sold. He just can't build a plot; in fact I don't think he even tries."

However, RM's Knopf sales proved disappointing as well, numbering under 4000 hardcover copies per title, only somewhat better than the average for mysteries of 3000. In 1953 Knopf wrote Chandler asking him whether he had retired from mystery writing (this was a year before the publication of The Long Goodbye); and Nolan speculates that Knopf, disappointed with RM's sales, was hoping to lure Chandler back into the fold.

Chandler replied that "in a way I regret that I was ever persuaded to leave you....But I did, and a man can't keep jumping from publisher to publisher. Anyhow, you have your hard-boiled writer now, and for a house of your standing, one is enough." Nolan suggests that Chandler was hinting he might jump back if only Knopf sacked RM!

A few years later in 1958, when English crime writer and critic Julian Symons was compiling a list of the 100 Best Crime Stories for the Sunday Times, he was urged by his editor to solicit contributions from other mystery writers as well, a proposition to which he assented though he wasn't crazy about it. One of the writers he contacted about a submission, Symons later noted in 1973, was none other than Raymond Chandler, who was living in England at the time, drinking himself to death.

"I remember one day at Helga Greene's flat when [Chandler] lay on a sofa talking, with a drink just behind his shoulder," Symons mordantly recalled, "which [Greene] constantly diluted as she replenished it." Somewhat disingenuously Symons writes in 1973 that it was his idea to ask other writers to participate in the Best Crime Story list, though many years later he admitted it was anything but:

I had what seemed the bright idea of getting famous writers to choose three or four books, although this didn't work out too well in practice, so that in the end I chose 90 per cent of the books myself.

It certainly didn't work with Chandler, who for the most part picked tough, little known American thrillers. While we talked about the idea, he sipped a little champagne before lunch, said Helga was a marvelous cook but ate hardly anything, and later sat back with diluted whisky talking pontifically.

It was clear he didn't like being contradicted, at least by me, although he kept saying I was a critic and had read 20 times more crime stories than he had even heard of, so why come to him, and so on....he seemed to me rather fussy and old womanish.

By 1973 Symons had gotten to know RM well and he observed in his Chandler piece that "something about Macdonald's work rankled [him]....When...he sent me his list of books for the '100 best crime stories' (I didn't use any of them), he remarked that he 'omitted numerous gentlemen who have paid me the compliment of imitation,' and this was principally a hit at Macdonald."

It looks like Chandler had just written off RM as a pretentious imitator of himself, which is a shame. Chandler died in 1959, the year RM published what most people consider his breakthrough book, The Galton Case, but I'm guessing the later RM novels wouldn't have appealed to Chandler either, largely because he probably wouldn't have had much empathy for what RM's critics have dismissed psychological naval-gazing. As Symons wrote in 1973:

Macdonald's recent novels dig into the past, looking for a family secret, a distant traumatic event which influences the present. By contrast, Chandler offers a series of sparkling surfaces, below which he doesn't care to look. And he doesn't want us to look below the surface either.

There was a resistance among many Golden Age crime writers, whether of the classic or hard-boiled variety, to looking beneath those surfaces. RM spent years in analysis. Can one imagine Chandler doing so? Or Hammett? Or Agatha Christie? Or John Dickson Carr? Or Edmund Crispin? Or Dorothy L. Sayers?

*******

In contrast with his later books, RM's early work may not dig deep into the lurid pasts of dysfunctional families, but it's damn interesting on its own merits and comparable to or better than Forties Chandler, in my view. Imitative? To some extent, yes.

There's violence, to be sure. Archer gets sapped with the best of the private dicks and is somehow as resistant to serious concussion as Chandler's Philip Marlowe. And Archer at this time was more flippant and wisecracking in the manner of Marlowe "You caught my with my veracity down," he tells a hood. "When you cock a gun at me it breaks up my conversation." On another occasion he comments, "I sneered back," a characteristic Marlowe response.

There are plenty of Marlowe style similes and doubtlessly some of them are overelaborate, like Chandler though of themt, and misfire. But overall the writing is the stuff of of beauty: "a tarnished gold Christ writhed on a dark wood cross"; "The bottles was thickly crusted with the meltings of other candles, like clotted blood"; "boys with hot-rod bowels, comic-book imaginations"; "The night died gradually, bleeding away in words"--there's lots of lines like that and it make the book come alive.

RM was 27 years younger than Chandler, with a brilliant, challenging wife and a precocious though troubled daughter. I think he had more genuine contact with mid-century life than Chandler and that contact informs his writing and enhances the social realism of it. I should mention here that there's a smashing sequence at a "professional" wresting arena.

The plotting is first rate too. RM even deigns to include material clues The Way Some People Die! I've defended Chandler's plotting, which is pretty good in several books in my opinion, but in his heyday RM was the better plotter of the two men.

And Archer does have empathy, particularly for several females he encounters in the case: a young teenage heroin addict and player of the badger game; Galley's mother and Galley herself--though the latter is a more enigmatic preposition altogether. Pious Mrs. Lawrence pronounces of her only child: "She's always been so fascinating to men, and she's never realized how evil men can be," while a doubtful friend of Galley's ("If Audrey Graham was Galley's best friend, she had no friends") tells Archer that, to the contrary, Galley "was crazy for men." What is the story behind Galley, Galatea, whose name recalls the mythical statue carved of ivory by Pygmalion of Cyprus, which springs into beauteous life?

After terming Raymond Chandler "fussy and old womanish," Julian Symons ruefully confessed: "It is disconcerting, to me at least, to find that a a writer of tough crime stories is like this....I suppose I shouldn't have been surprised. Most British crime writers are amiable neutered tabbies, but I expected Chandler to be different." Of RM, however, he added: "Ross Macdonald is a quiet and gentle man, but beneath the gentleness you sense a reserve of streel. I didn't feel this in Chandler."

Symons deemed Chandler and Macdonald comparably important crime writers, though over both of them he favored Hammett, whom he deemed the toughest of them all. Hammett "always behaved," noted Symons, citing a Hammett friend, "as if he wasn't going to live beyond Thursday week." But for me RM in his tough phase was tough enough. I think it's time we started giving the best of his early, "Chandleresque" Lew Archer books more respect. The Way Some People Die is hard enough and strong enough to last long in any crime writers pantheon.

.jpg)

.jpg)