The Menace on the Downs is a frustrating book to me, because one feels that it should be better than it is. While there are some good parts to it, the novel is more "interesting" than it is "good," I would say. Interesting for its material, that is, rather than for how the author handles the material in an entertaining fashion. It's really rather plodding, predicatable and dull on the whole, without any compensating ingenuity on the part of the frequently ingenious author.

Miles Burton was noted for the authentic rural settings of his mysteries, and The Menace on the Downs certainly offers one of the most rural of his rural settings. John Street, aka Miles Burton, published the novel in 1931, the year after one of his most memorable detective novels, The Secret of High Eldersham, and its sequel of sorts, The Three Crimes, both of which feature the investigative team of Scotland Yard's Inspector Young and his gentleman amateur sleuthing buddy, Desmond Merrion.

Young exited the Miles Burton books after The Three Crimes, although Merrion would return in 1932 in Death of Mr. Gantley and remain until the the Miles Burton books came to an end in 1960. In the meantime there was this odd little number, The Menace on the Downs, in which neither Young nor Merrion appears but where we do see the debut of Inspector Arnold, who features in almost all of the Miles Burton novels from here on out, usually in the insouciant company of Merrion.

|

| What menace lurks on the English downs? You'll never guess! (Actually, you will.) |

Like The Secret of High Eldersham, Menace on the Downs draws on European folklore, but where Eldersham is exciting and moves at a good clip, Downs just trudges along in the country muck. It's a shame because the material should be rather thrilling.

Significantly, the novel opens with a quotation from philosemitic Czech writer Oskar Donath on the Polna Ritual Murder case, in which, in Austria-Hungary at the turn of the nineteenth century, a Jewish man, Leopold Hilsner, was tried, convicted and sentenced to death for ritually murdering a teenaged Czech Catholic girl, who was found dead in some woods with her throat cut and little blood around her body:

The medical evidence called by the prosecution showed that insufficient blood had been found to account for the bloodless condition of the body.

|

| autopsy on victim in the Polna Ritual Murder Case |

At the time an enlightened Czech college professor, Tomas Masaryk, played a major role in having Hilsner's death sentence commuted to life imprisonment by Austro-Hungary's Emperor Franz Josef. Hilsner would finally be pardoned in 1918 by Franz-Josef's briefly ruling successor, Emperor Karl.

Masaryk himself went on to become the first president of Czechoslovakia and one of Europe's most admired between-the-wars statesmen. John Street for his part published a biography of Masaryk in 1930, a year before he published The Menace on the Downs, in which he castigated the Polna Ritual Murder case as an outbreak of pernicious European primitivism.

At the same time, however, he obviously decided he might be able to make use of the case for one of his Miles Burton thrillers. (More recently, the events in the Polna Ritual Murder case were dramatized in the 2016 Czech film Murder in Polna, which is highly recommended to people interested in this dreadful subject.)

|

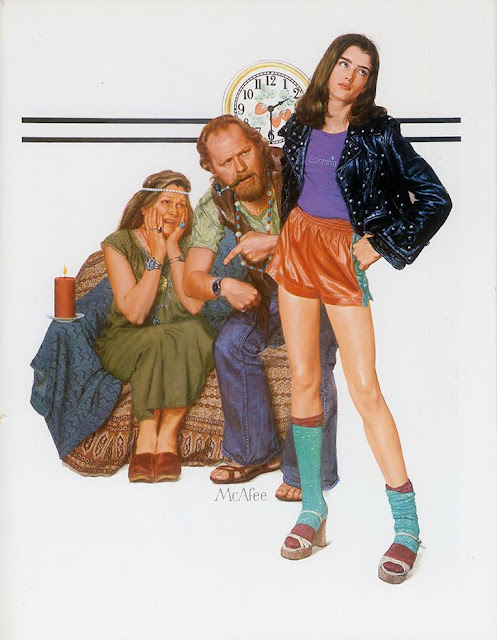

| Leopold Hilsner (Karel Hermanek) charged with the blood libel in the film Murder in Polna |

Let me emphasize that there are no Jews in The Menace on the Downs, so the book is in no way an endorsement of the blood libel, which Street expressly and vigorously disavowed in his Masaryk biography. Rather in Downs the culprit--and this is so obvious that I'm giving nothing away if by chance you ever come upon a copy of this book--is...

the head of a religious group numbering some several hundreds, known as the Dukeites.

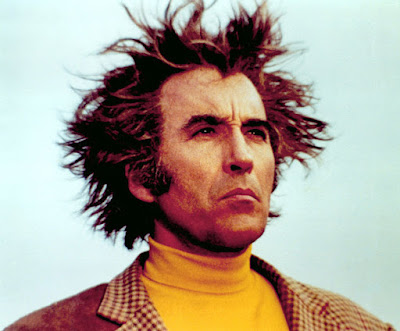

In some ways the book reminded me of the recent horror film Midsommar (2019) and an older one (now nearly fifty years old in fact), The Wicker Man (1973), but unfortunately Street's tale is so ploddingly told that it's entirely lacking in the delicious frissons of fear and unease which distinguish these eerie films.

Where The Secret of High Eldersham is a thriller with a mystery and detective element, The Menace on the Downs is a thriller that gets buried buried by the dullish (in this case) mechanics of detection. In some ways it almost feels like a police procedural, which makes it interesting to the genre historian, but not necessarily entertaining.

It all starts in a rural English district (likely in south central England) with the discovery, on the afternoon of December 22 (hmmmm), the day after winter solstice, of the dead body of Sidney Harper, a teenage delivery boy.

The boy's throat has been cut and his head and neck lie in shallows at the edge of a stream, with a jagged broken bottle nearby. Little blood is present, the fluid presumably having emptied into the stream. Sidney's bicycle is nowhere to be found.

Was Sidney's death accident, suicide or murder? Local police are disinclined to think it's murder, as they can't conceive of any motive anyone might have had for murdering a boy. (No one conceives that it might have been a sex crime, even though sadistic sexual maniac Fritz Harman was executed just six years earlier for assaulting and murdering more than a score of men and boys.)

In fact the only suspect anyone can think of is the boy's no-account laborer father. Nor does it seem likely that young Sidney would have killed himself. If an accident, the boy must have skidded off the road and cut his throat on the broken bottle as he fell. But then where is his bicycle?

Eventually police end up arresting Sidney's father, but the case collapses when Mr. Winterbourne, wealthy landowner and head of the Dukeites, provides an alibi for the man. This takes up the first 160 pages of the book (believe it or not), which essentially up until this time is a rural police procedural, although no one used that term back then.

Veringhame is an expert on Central Europe and has written about Tomas Masaryk and knows all about the Polna Ritual Murder case, although amazingly he fails to connect any of this with the local murder it so queerly resembles--or the one which follows it.

Yes, after the police case against Sidney's father collapses, leaving the boy's death unsolved, yet another boy is found dead in very queer circumstances six months later--on June 22 to be precise (hmmmm), the day after the summer solstice. What's the deal with these solstices, anyway?

Well, the riddle is all-too-obvious to modern readers, schooled on The Wicker Man and Midsommar. Actually even if you haven't seen these films it's all-too-obvious.

It's the time of the season for murder, you might say.

The novel, which is over 80,000 words long, spends so much time on the plodding construction of the obviously misguided case against Sidney's father that we lose the sense of thrill and horror which Street genuinely captured in The Secret of High Eldersham.

After the second boy is found dead and Inspector Arnold from Scotland Yard shows up (three-quarters of the way into the novel), things finally pick up a bit, but it's much too late. Arnold manages to solve the case, but only because he speaks German (a skill never hinted at in later books) and idly reads about the Polna Ritual Murder case in one of Veringhame's history books. Problem solved! Mr. Winterbourne meets a suitably dramatic end. Story over. Yawn.

I just wish the tale had been better told. As it stands it's mostly of antiquarian interest, as it were. Miles Burton had done better in Eldersham and he would go on to do better over a prolific three decade career.

I must say, though, that the thought of the horrific actions performed at a setting like the Great Coxwell Barn is distinctly creepy! It just doesn't translate in this book where the "shocks" are kept too distanced from the reader. If you're going to write a shocker, be sure to shock!