Rebecca Rego Barry is a writer and editor who lives in New York’s Hudson Valley. Her articles and essays about books, history, and collectibles have appeared in Financial Times, Literary Hub, CrimeReads, Atlas Obscura, Lapham’s Quarterly, Smithsonian Magazine, The Guardian, The Public Domain Review, Fine Books Magazine, and elsewhere.

Her first book, Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic

Finds in Unlikely Places, was published in 2015.

Nearly a decade later, in February 2024, she is publishing a book about popular

Golden Age mystery writer (and many other things) Carolyn Wells, called The Vanishing of Carolyn Wells: Investigations into a Forgotten Mystery writer, about which I

interviewed her a few months ago.—The Passing Tramp

INTERVIEW

PT: It is so nice to talk with you Rebecca. So, just how did you get interested in Carolyn Wells?

|

| Carolyn Wells |

RRB: I have always

loved "old books," and am something of a collector.

In 2011, my

husband bought me a first edition of Walden that had Carolyn Wells’

bookplate in it. I had no idea then who she was, but I began to see her name

(as author) on books at the antiquarian book fairs I attend. It took years for

me to figure out that they were one and the same!

Carolyn was an author, also a

librarian before that, and a book collector later in life. Needless to say, I began to buy some of her

books, and some of the books she had once owned.

When that new edition

of Murder in the Bookshop came out -- the one for which you wrote the

introduction -- everything really came together, and I became more interested

in her as a person, and a writer who had been almost entirely forgotten

PT: I remember you

published an article at Crimereads about her.

RRB: Yes, that was

really the turning point. Once I wrote that, I thought, hmmm, this could be a

bigger project. I had just finished or

was reading Mallory O'Meara's book called The Lady from the Black Lagoon

that was all about revitalizing the legacy of a creative woman. (http://www.malloryomeara.com/theladyfromtheblacklagoon)

The Lady from The Black Lagoon — Mallory O'Meara

|

| Carolyn Wells |

PT: I wrote an essay

on her crime fiction in 2014, which was published in a tribute book to John

Dickson Carr biographer Douglas G. Greene.

Carr, the great locked room mystery writer, was as you know a great fan

of her work in his earlier years.

RRB: Yes, of course

I've read your essay! Oh, but Carr...! He ended up stabbing her in the back. He was a fan--until he wasn't.

PT: Well, that brings up an interesting point: Carolyn Wells’ literary

reputation. Ups and downs you might

say. But back in the Twenties and Thirties

she was really tremendously popular in the United States at least. All during the Golden Age of detective

fiction. Why do you think she was so

popular?

RRB: I think the

phrase you used once was "critically bulletproof," and I borrowed the

"Bulletproof" part for one of my chapters. She was very popular, and

not just because of the mysteries; she had a built a reputation as a witty

poet, a puzzle master, and a Young Adult author, so her name was really

everywhere. But to your question: she

said many times she merely wanted to entertain and amuse (and make money). She

wasn't in it to be a literary "genius," even though I think it is an

arguable point.

PT: She wrote in so

many genres, didn’t she? What were the

children’s book series, Marjorie and Patty?

A few years back I found a blog devoted to those books where the

commenters, who I imagine all were women, were fondly discussing how much they

loved Marjorie and Patty tales, probably into the 1950s and 1960s.

RRB: Definitely.

There were several series ... Patty, Marjorie, Betty, Dorrance, etc. Patty was

the longest running and most successful. They were middle/upper-middle class

manners stories, very sweet. Librarians liked them, and that helped. There

weren't many girls' books at the time (1901-19). When I looked at digital copies -- through the Internet Archive, etc. -- so many had sweet

inscriptions to young girls from mothers, grandmothers, aunts. They were

cherished books.

PT: Sort of

forerunners of Nancy Drew and Judy Bolton, I suppose, except that Marjorie and

Patty, et al, didn’t actually solve mysteries, I suppose.

RRB: Right. They were

on adventures, on holidays, learned how to 'homemakers,' that kind of thing.

PT: And then there was

the so-called “nonsense” literature Wells wrote. Can you explain that genre to people. Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll?

RRB: Lear and Carroll

were her absolute favorites. Actually, I

own one of the editions of Lear that was Carolyn's--what a treasure! The

nonsense is hard to define, but it’s combinations of puns, witticisms, limericks,

etc. She actually created five anthologies for Scribner, all various forms of

light verse. Nonsense is how she cracked

into the literary world, pitching magazines like Puck and The Lark in the mid-1890s.

PT: She had a novel Ptomaine

Street I recall, a satire of Sinclair Lewis’ celebrated novel Main

Street, that I have meant to read for years.

RRB: She didn't seem

to hold grudges, but she had no problem poking fun at authors -- Henry James

was another target -- and she could be deliciously mean. Parody, she loved!

PT: So, it seems like

Wells had this really humorous outlook on life, but in real life she faced

tragedy that she concealed behind a smile.

Can you tell us about that?

RRB: True. I mean,

it's important to note that her upbringing was rather privileged. Big house,

maids to help. But she also lost siblings to disease, and, in one case, where

her sister died of scarlet fever, she too contracted it which caused her nearly

complete hearing loss in one ear. That troubled her for the rest of her life. Also, she stayed in her parents' home in NJ

until she married, late in life, which probably speaks to her traditionalist

ideas. She married late, and sadly he died only eighteen months later, so that

happiness was fleeting.

PT: That was to Hadwin Houghton? I always loved that name! Like a character from an English mystery.

RRB: Yes. And everyone

always thinks he worked in publishing -- but he didn't!

PT: He was a cousin of

the publisher or something like that?

RRB: She says cousin

in her memoir, but I think it was second or cousin x removed, because I tried

to find more information on him and so little is available. I traced his

parents and brother, but none were in publishing. Unless you count a trade magazine called Varnish

that he and his brother worked on.

PT: He worked for a paint company?

RRB: Yes, Valentine

& Co. (merged and melded, now Valspar). Made a great living. How they met

is something I discuss in the book because there are two origin stories. The

one I prefer describes him as a puzzle lover, and she made puzzles. Supposedly

he would mail in his answers and they started corresponding. Another odd bit of her life: crossword puzzle

maker!

PT: I thought she

wrote some of her best books during the short time she was with him. I gather

it was a very happy union.

RRB: Yes, I think so,

he moved her to NYC, and she loved that. Loved living there, and stayed there

until her death.

PT: Well, that brings

us to the mysteries. Carolyn was writing nonsense lit, she was writing parodies

and children's books, how did she get started on mysteries?

RRB: I think the short

answer is: she loved reading them, especially Sherlock Holmes, and like all the

other forms she tried, so just figured she could do it, and she did. Her first

mystery story appears in 1905, and the first book form, The Clue, in

1909. She saw the market for mysteries,

and worked to fill it. Same with Young adult. Same with film scripts. She was

quite savvy that way. Side note: one of the things I love about CW is that she starts this entirely

new career in her mid-forties.

PT: What was her first

published mystery story?

RBB: The first I could

trace is called "Christabel's Crystal" published in a Chicago

newspaper on October 15, 1905

PT: I see that ‘Christabel’s

Crystal’ was published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine in 1997. https://the.hitchcock.zone/wiki/Carolyn_Wells

RBB: Yes! I bought

that 1997 mag recently to read the story for myself. She wrote 81 mystery novels in total; 61 of

which were her "Fleming Stone" detective novels. Although, then

again, there's one Fleming Stone novella, “His Hand and Seal,” from 1911

published in Lippincott's and made into a film, but never published in book form.

So, maybe more than 81/61.

Carolyn was involved

in 16 films, to varying degrees: mainly, writing the 'scenario' as they called

it. Half of those were with Edison. The

film His Hand and Seal came out in 1915.

It was done by the Biograph Co.

PT: So these were

filmed in the New York area? I just checked imdb and saw I think five mystery

films, all from the 1910s, based on her work. Any of those survived?

RBB: Most were filmed

in the New York area, as it was largely before the industry's big move to

Hollywood. I devote a whole chapter to this part of Carolyn's life and my

endeavors to track down one of the films she worked on. Here's another neat film she worked on: Dearie

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0017795/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1. That was the last one.

PT: So her detective

Fleming Stone was an early film detective too. Let's talk in some more detail

on her mysteries, since this is a mystery blog! Some academic writers have

written in the last decade or so about how Wells actually helped establish some

of the tropes of the Golden Age mystery. Can you elaborate on that?

RBB: That is part of

my argument, though not just with mysteries. She has helped to define so many

genres, really putting in the world, only to be overlooked later on. But yes, locked-room mysteries and

country-house mysteries -- that was her bread and butter. It's true characterization wasn't her strong

point; she felt the puzzle was the best part of a mystery.

PT: Well, people

really valued the puzzle at that time. I think my friend Bill Pronzini helped

undermine her reputation with his book Gun in Cheek--ironically, the

sort of humorous book she might have written--because he made fun of the lack

of realism in her books, the reliance on secret passages--a no-no in many purists’

eyes.

RBB: I can see from

contemporary media accounts that she was one of two women credited as a popular

mystery author during the WWI era. The

other being Mary Roberts Rinehart. I

appreciate Pronzini's insight though, and at least he included her in the

discussion!

PT: Yes, Mary Roberts

Rinehart was hugely popular and later many critics--male critics--undermined

her for writing what they dismissed as Had I But Known mystery, all full foreshadowing

and grim forebodings.

RBB: Yeah, there was a

lot of sexism even in the reviews of time, like this book was good, "even

though it was written by a woman." Seriously! Not sure Carr helped on that score, calling Carolyn

and others "lost ladies."

PT: I look at my own

evolution on Wells as people can see on the internet, where in 2009 at

MysteryFile I'm taking the line like Bill that she was kind of this magnificently

"silly" writer, but by 2014 I had read Vicky Van and I

actually quite liked that one. And then over the next several years I found

some more by her I liked, a couple of these The Furthest Fury and The

Daughter of the House. So then I do this blog piece in 2018, "How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Carolyn

Wells."

RBB: She definitely

wrote some good mysteries! Another blogger, John Norris, has written a good bit

about her and he quite likes her Pennington Wise and Zizi series, though it's

much shorter than the Fleming Stone one. I too liked Vicky Van, also Murder

in the Bookshop. It's funny though, I'll hear how one person (scholar,

collector, vintage mystery buff) loved one of her novels, only to have another

person say it's terrible. It's all subjective!

But for me the point

of the biography was not necessarily to delve into which books are the best,

but just to give credit where credit is due. Obviously, the readers of her time

loved her, so that's important to look at.

PT: Yes, I think people need to remember she was really very popular. I was just reading, for an article I wrote on Eden Phillpotts, a contemporary author who also wrote mysteries, about how they were corresponding in the late 1930s and Phillpotts dedicated his mystery Monkshood to her.

She made some very positive statements about his writing that were blurbed in the press, because her opinion mattered to people.

RBB: That's so

interesting. She did say he was one of her favorites, and they were pen pals --

a packet of their correspondence went to auction after her death. Chesterton was a fan of Wells, too. As was Van Dine. Vincent Starrett, however, hated her!

PT: I wish I had that

correspondence! If you look to Twenties and Thirties America, three of the most

popular prolific mystery writers were Wells, Phillpotts and JS Fletcher, the

latter two Englishmen.

They were all born around 1862 and later, certainly by the Forties, came to

be seen as terribly old-fashioned, but when people get to read their books today, they often

enjoy them.

Starrett was not a fan of Wells though?

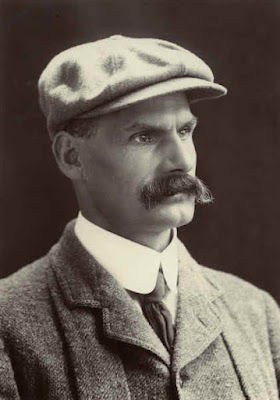

|

| Vincent Starrett |

RBB: Oh, did Starrett

hate her work. Starrett was a book

collector, like Wells, and I think he was jealous of her wealth and that she

could buy whatever rare books she wanted.

He also said nasty things about her books, like: "It would give me

pleasure to annihilate Carolyn, if not for her Atlantic article, for her

abominable detective novels probably the worst ever written.”

PT: Ouch! I'll have to

get the citation for that Starrett review. He made his opinion clear!

I found one record

that indicated Wells averaged about 13,000 copies sold per mystery, which

actually put her in the higher echelon of mystery writers throughout the

Twenties and Thirties. So something in her work struck chord with people. And

that is just actual sales, not library rentals. Her reading public must have

been much bigger.

RBB: I agree, and I

found some archival documents -- royalties, etc. showing some of her books

selling that many and more. Also, a public library survey from 1936 that put

her among the most circulated.

PT: Very interesting, I

am not surprised about her sales and circulation. I think the thing is, though, that she wrote

a lot and was quite varied in her book quality. I especially like the ones with

Fleming Stone's Irish boy sidekick Fibsy MCGuire. They are the Batman and Robin

of GA mystery.

|

Fibsy in action in

The Mark of Cain (1917) |

RBB: Yes, reviewers

liked Fibsy too. Alas, Mary Roberts

Rinehart always sold more!

PT: So you published

an article about Wells in 2020 and then you wrote a book about her. What is it

called and when is it out?

RBB: It's called The

Vanishing of Carolyn Wells: Investigations into a Forgotten Mystery Author

and it will be out Feb. 13, 2024. Title

based on one of CW's mysteries, The Vanishing of Betty Varian.

PT: I've been meaning

to read that one! Who is publishing your book?

RBB: PostHill Press: https://posthillpress.com/book/the-vanishing-of-carolyn-wells-investigations-into-a-forgotten-mystery-author

PT: I congratulate

you. I certainly found myself getting fascinated with Carolyn Wells over the

years, though of course I look mostly at her mysteries. How notable a figure do

you think she was in American writing, and do you think she will ever get her

due?

RBB: Thanks! I hope

this book will go some way toward bringing her "out of the shadows"

(see this article from earlier this week: https://www.nysun.com/article/poem-of-the-day-how-to-tell-the-wild-animals) Poem of the Day: ‘How To Tell the Wild Animals’

I think she was

notable in many ways -- a woman who really earned her place in the literary

ecosystem, who not only crossed genre but helped build those genres into what

they became. She has an incredible

legacy that deserves attention.

PT: I think the thing

is, critics come and go, but readers remain. I was checking on Amazon, one of

the Carolyn Wells Mystery Megapacks has almost 270 reviews of her copyright

free mysteries, average 4 stars. A lot of favorable reviews. And HarperCollins has reprinted Murder in

the Bookshop as you mentioned and I think Otto Penzler at Mysterious Press

has done some of hers as well. It would be nice to see get some more quality

reprints.

RBB: I have been

trying to jumpstart a reprint or two. One of Carolyn's stories is in Otto's new

anthology of bibliomysteries, so that's cool.

Otto actually blurbed my book! He said I changed his mind about Carolyn

Wells. It reads:

“The Vanishing of

Carolyn Wells is a remarkably compelling narrative about this astonishingly

prolific author who had great success in numerous genres. While I have never

been a great fan of Ms. Wells’ mystery novels, the sprightly and perceptive

prose of Rebecca Rego Barry’s worthwhile study has convinced me to give her

another try.”

Little by little her

name will get out there.

https://www.amazon.com/Golden-Age-Bibliomysteries-Otto-Penzler/dp/1613164203/ref=asc_df_1613164203

PT: Very nice! Well, I

wish you and Carolyn both great success. I always enjoy getting the chance to

talk about her work. One more thing I wanted to mention, Carolyn's first job

was a librarian in her hometown of Rahway, New Jersey, correct? I wanted to

make a shout-out to all the hard-working librarians out there.

RBB: Yes, she was a

librarian in Rahway for a decade, another interesting facet to her life!

PT: Bless the

librarians in the censorious times. Thanks, Rebecca, enjoyed it!

RBB: Me too! Thanks so

much!