Introduction

I'm already doing cleanup on my last, extremely long blog post, which is all about vintage crime writer

Nigel Morland (1905-1986). For example,

The Phantom Gunman was not actually the first Morland Mrs. Pym mystery as many sources state, but rather

The Moon Murders (as

John Norris states in his review). That's my mistake, made because I have neither of those (very rare) books; but another possible error in my last post, indeed I think a probable one, would be due to a major misrepresentations made by Morland himself, along with his publishers.

Was Nigel Morland really Edgar Wallace's private secretary at some point, as was claimed? Even as I typed this assertion I tended to doubt it. When would this have happened? But authors--and publishers--don't ever lie, do they? Perish the thought! Yet...

I.

As explained last time, Nigel Morland was born Carl van Biene in London on June 24, 1905, putting him at the younger age range of GA crime writers, along with, for example,

Margery Allingham (1904-1966) and

John Dickson Carr (1906-1977). He grew up at a nice address in Tooting, northern London with his presumably Protestant mother,

Gertrude Ada Brown, evidently the daughter of a civil servant. His Jewish father, a musician named

Benjamin (formerly Benoit) van Biene, a son of famed cellist and actor

Auguste (formerly Ezechiel) van Biene, seems to have left his wife and child not long after Carl was born. By 1911 he was living apart from his family and declaring himself single, while Gertrude was maintaining that she was still married.

After the Great War Benjamin had his name officially changed to

Barton van Biene (new name, new life) and in 1922 he married, presumably legally, another woman, Edith Myra Wesley, also a daughter of a civil servant. Maybe in the UK the thing was civil servants' daughters rather than farmers' daughters? This marriage stuck, however. Barton, as he called himself now, died in 1939 at the age of 58 in the north London suburb of Muswell Hill, leaving in modern worth the modest sum of about 8300 pounds (about 10,300 dollars) to his widow Edith.

|

teller of tales (in more way than one?)

Nigel Morland (1950s?) |

What were Carl aka Nigel and his mother Gertrude doing in these years? Well, according to Nigel (I'll stick to this name now), Gertrude became associated sometime around the start of the Great War with famed crime thriller writer

Edgar Wallace, in the Twenties the bestselling author in the UK. (It is said that in 1928 one out of four books sold there was by Wallace.)

Wallace lived with his wife and children at a flat in swanky

Clarence Gate Gardens, next to

Regent's Park in

Marlyebone, about six miles due south of the Van Benoits, mother and son, resided. Frequently, according to Nigel, his mother was there, often with Nigel in tow. Nigel later wrote of this experience in a 1981 article, "

A Day with Edgar Wallace," which is referenced in

Neil Clark's recent biography of the Thriller King.

According to Nigel, Gertrude had been employed by Wallace during the latter years of the Great War as a "

presiding Mother-Friend-Counsellor-Manager--PRO or what have you." (This is rather amorphous--What have you, indeed!)

Young Nigel, who would have been about ten to fourteen years old at the time, thereby spent a great deal of his time at the flat at Clarence Gate Gardens in the company of the Great Man, whom he idolized. (He even had his own key to the flat.) According to Nigel, Wallace called him "Niggie"--I hope the first "i" was long--and once Wallace even bought "Niggie" an expensive scooter at Harrods when the poor lad was convalescing from an illness.

|

Edgar Wallace (1875-1932)

"He was like a human dynamo to be with--

you just could not get enough of his company."

--Nigel Morland (1905-1986) |

But where, pray, does Nigel being Edgar Wallace's secretary come in exactly? Presumably Wallace did not hire adolescent boy secretaries. To be sure, his longtime secretary,

Robert George Curtis (1889-1936), who typed all of Wallace dictated novels, had joined the armed forces in 1915, when Nigel was ten. However, Curtis' replacement was eighteen-year-old

Violet Ethel King (1896-1933), a brunette bobbed daughter of a Battersea solicitor and newly minted secretarial college graduate. She remained in the position until Curtis returned from the war in 1919. (Two years later, incidentally, the not so shrinking Violet became the second wife of Wallace, who was over two decades her elder.)

Curtis stayed with Wallace for the rest of the author's life, and was

with him at his death in 1932 in Hollywood, where he had been working on

the script of the film

King Kong. Neil Clark does mention that Wallace hired a supplementary correspondence secretary, twenty-three-year-old

Jenia Reisser, an attractive Russian emigre, but nowhere does he mention Nigel Morland performing in any such a capacity. Aside from the redoubtable Curtis, Wallace seems to have been drawn to pretty and pert young women as secretaries.

|

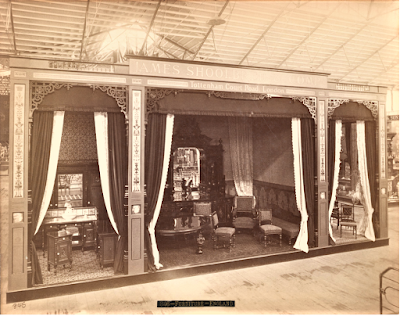

posh Clarence Gate Gardens

where Edgar Wallace lived with

his menage at the time during

the Great War when Nigel Morland

claimed he regularly visited him |

All I really know about Morland's whereabouts in the Twenties is that on December 9, 1922, when he was only 17, he indeed did embark for China, as he claimed, aboard

S. S. Teiresias, listing his occupation as "printer" and his home address as the not exactly posh 19 Crouch Hill,

Stroud Green, London (today the home of

Max's Sandwich Shop, which, incidentally, has produced

this book).

Nigel spent 1923 in Shanghai, where he is said to have worked as a journalist of some sort for the

Shanghai Mercury and where he published his first fiction, including a short story, "

The Thousandth Man," in

Shanghai Stories, the first short fiction anthology published by the

Shanghai Short Story Club, which met every month in the city. Nigel surely must have been about the Club's youngest member.

Nigel

seems to have spent some considerable time in the United States too, on

the West Coast. (Certainly Nigel's books evince familiarity with the

good old U. S. of A.) By 1930, however, he was back in the mother

country, where he had made the acquaintance of the artistically

inclined Peggy Barwell, a daughter of a wealthy furniture store

executive. For a couple of years the two together published several

books (non-criminous) before marrying in 1932, the same year Edgar

Wallace died.

So when it was that Nigel might have been employed as Wallace's secretary, I just don't know. Perhaps Nigel used to fetch cups of sweet tea for the Great Man, a notoriously copious imbiber, back during the Great War? But it's rather a long distance to go from Edgar Wallace's private secretary to Edgar Wallace's

chai wallah.

|

| 19 Crouch Hill, Stroud Green (today home of Max's Sandwich Shop) |

As mentioned I don't have a copy of

The Moon Murders,

the first of Nigel Morland's Mrs. Pym mysteries, which when it was

published in 1935, when Nigel was 29, made his name in the crime fiction

genre, however equivocally. On the jacket, I see from internet images,

it says nothing about Edgar Wallace, though the symbol on the jacket,

which Morland used for the rest of his life as a mystery writer, bears a

marked resemblance to Wallace's famous crimson circle. However,

John Norris

in his review of the novel notes that Morland dedicated the book to the

memory of Wallace and credited Wallace with inspiring the character of

Mrs. Pym.

That notwithstanding, the real push for Nigel Morland as the western

world's "new Edgar Wallace" seems to have come with the first

publication of a Mrs. Pym novel in the United States,

The Clue of the Bricklayer's Aunt

(review coming soon), in 1937. (It was the fourth Mrs. Pym crime

novel, published in the UK the previous year, immediately after

The Street of the Leopard.) To an English crime writer, snagging American book sales was a very big deal indeed.

Aunt's American publisher,

Farrar & Rinehart, did not hold back on the ballyhoo, no indeed:

Introducing a Mystery Writer whom Edgar Wallace nominated as his Literary Successor....

Edgar

Wallace, before he died, trained a young man to follow in his

footsteps, and furthermore he created and gave to the young man the germ

of a character, "Mrs. Pym of the C. I. D."

Weeellll, this is getting pretty florid and fancy, I must admit. Yet it should be

noted that, however exaggerated this may be, Nigel's mother Gertrude had

at least one definite verifiable connection to Edgar Wallace. In 1927

she married

Edward Ashley Lomax, a 42-year-old "gentleman of independent means"--yes, he's actually described that way--who owned the mansion of

Grouville Court on the

Isle of Jersey. Lomax--or perhaps his wife?--claimed the copyright to the 1928 Edgar Wallace crime thriller play

The Man Who Changed His Name. (With such a title this play could have been about Nigel Morland and himself and his forbears.) Lomax died in 1946, incidentally, leaving Gertrude with an inheritance valued in modern worth at about 1.5 million pounds (1.8 million dollars). So she had come up in the world quite a great deal since her marriage to Benoit/Benjamin/Barton van Biene.

|

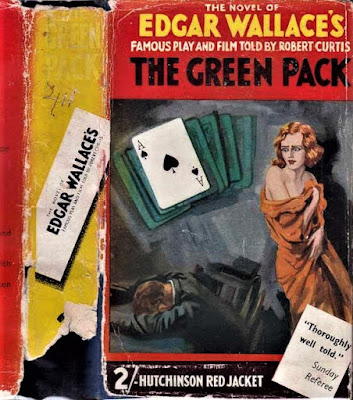

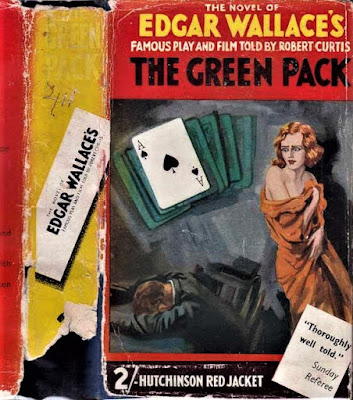

This Robert Curtis thriller was based on

an Edgar Wallace play that opened when

Wallace lay on his deathbed in Hollywood |

The play, which was not one of Wallace's more successful ones, was

later adapted as a novel by Robert Curtis, who in the brief time between

Edgar Wallace's death and his own untimely demise strove to grab

Wallace's crown by publishing thrillers based on the Great Man's plays

and film scenarios, the last shreds of fiction with actual links to

Wallace's own imagination.

I think it's interesting that the more grandiose claims about Nigel's relationship with Wallace only were advanced, apparently,

after

the death of (1) Wallace's second wife (his first wife had already

predeceased him) and (2) his actual private secretary, Robert Curtis.

Indeed, if you want to get bookish, the most untimely deaths of Mrs. Wallace (age 37) and the private

secretary (age 47), following so rapidly on the heels of the Master (age 56)

would make a great plot for a Golden Age murder mystery. It's like something out of

Agatha Christie's A Pocket Full of Rye. Whodunit? I'm

looking at you, Nigel! (Okay, just kidding.)

There were three older Wallace children from his first marriage, who were roughly Nigel's own

age, but the primary heir of the Wallace estate--which when Wallace died

consisted mostly of debts incurred from his lavish spending, though

this was soon turned around from book sales--was Wallace's beloved

daughter from his second marriage, Penelope, who was only eight years

old when her father died. So Nigel may have believed that he was free to

aggrandize himself vis-a-vis Wallace pretty much unchecked. Would

Nigel have done such a thing? The short answer seems to be is heck,

yeah, he would.

|

| S. S. Teiresias |

II.

Decades after Wallace's death, in the mid-Sixties, Nigel had taken over the editorship of

Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine and was promising that he had an Edgar Wallace biography in the works. (The latter was never published.) But his takeover of the editorship of EQMM was not effected without leaving bitter feelings in its wake on the part of the previous editor.

EWMM was started in 1964 by twenty-one-year-old

Keith Chapman, former editorial assistant of the

Sexton Blake Library. For a nominal fee the Edgar Wallace family allowed him the use of the Great Man's name for a crime fiction magazine, and soon EWMM was off and running.

But it didn't get very far. In a few months the company that owned the magazine found itself in a difficult financial position and the Wallace family stepped in, in the event sacking Chapman, who was left quite irate about the whole thing. Forty-four years later, he

complained about the affair at the website

Mystery*File, laying emphasis on what he deemed Nigel Morland's mendacious conduct:

|

the young Keith Chapman with Edgar's children

Brian Edgar Wallace and half sister Penelope

see James Reasoner's Rough Edges |

I have letters on file from Nigel Morland ostensibly offering me support, telling me how "impressed" he was [with EWMM], how it was "first class" and "excellent." But many [of these letters] were written when he must at least have had an eye on taking over my role.

"Dear Keith, I had the new issue, and really do think you are doing it well. You've set a standard, and that is a high one. So far you seem to better it a little with each issue, which, after all, is the heart of all really good editing.

Congratulations. Every good wish, Yours, Nigel."

Two months later after Morland wrote this letter, Chapman was fired and replaced by Nigel, whom, Chapman recalled,

"I was told by Penelope Wallace and her husband...was older and more experienced than me, and therefore would make a better job of the magazine."

Chapman claimed that many crime writers and contributors to EWMM supported him during this tough time, including

T.C.H. Jacobs, another Thirties pretender to Wallace's throne who had been a prime mover, like Morland, in the formation of the

Crime Writers Association. Jacobs wrote Chapman the following commiserating message:

Their choice of an editor astonishes me. I have known Morland for many years and am unaware he has ever had any editorial experience. But I do know that he has always claimed some connections with the Wallace family. Maybe it is true. I don't know. He is certainly older than you, sixty.

Chapman was at the helm of his brainchild EWMM for merely four months. Nigel Morland only made it for two and a half additional years before the magazine failed in 1967. Chapman seems to have seen it as poetic justice.

"...he has always claimed some connections with the Wallace family. Maybe it is true. I don't know."

And there you have it, in the form of T.C.H. Jacob's words, in a nutshell. Jacobs had known Nigel for years as a colleague and presumable a friend of sorts, but he didn't know whether what Nigel said, over and over and over again. about his connection to Edgar Wallace could be believed. Not much of an endorsement of Nigel's veracity.

III.

Other people have expressed similar doubts about Nigel's truthfulness. In the large community of devotees of the

Jack the Ripper murders, known as Ripperologists, Nigel's name, it doesn't seem an exaggeration to say, is mud. Why is this? Because in the community he is generally seen as, well, a liar or, shall we say more politely, a fabulist or fantasist.

In

Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates (2006),

Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow write that Nigel, a "

self-proclaimed criminologist," was one of the Ripper writers who had a habit of "

inventing tales that posed as factual events." In 1978 Nigel wrote the introduction to

Frank Spiering's 1978 book

Prince Jack: The True Story of Jack the Ripper, in which the author strenuously advances the theory that Queen Victoria's grandson

Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence (aka

Prince Eddy) was guilty of the Ripper murders. In it Nigel claimed that as a youngster he had become interested in the Ripper story when no less a personage than

Arthur Conan Doyle (But naturally!) told young Nigel that the identity of the Ripper belonged "

somewhere in the upper stratum." As Nigel put it decades later:

I was interested in the Ripper in a purely academic way when I was a youngster, intrigued by a mention to me by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Conan Doyle remarked to me that the Ripper was "somewhere in the upper stratum," but he would never enlarge upon that statement.

Had Sir Arthur just happened to come to over to have tea at the Edgar Wallaces at Clarence Gate Gardens when young "Niggie," that scamp, was there, or what? I don't know that Wallace and Doyle ever even actually met. (If anyone does, please let me know.) On an internet

message board Stewart P. Evans has commented humorously that the late criminologist

Richard Whittington-Egan "

knew Morland and said that if you mentioned Dr. Crippen to [him], Morland would then tell you how he sat on Crippen's knee as a child."

And, sure enough, Morland did tell people he had sat on Crippen's knee as a child. His nanny just happened to have take him on a visit to the Crippens, you see....Interestingly, one of the book Nigel published with Peggy Barwell was tellingly titled,

People We Have Never Met: A Book of Superficial Cameos (1931).

"

Morland had met just about anyone who was anybody in his day," observe Evans and his co-author Donald Rumbelow sarcastically in their book, before they dig into Nigel's claim of having in the Twenties interviewed

Chief Inspector Frederick Abberline, one of the lead investigators of the Ripper case (this around the time he was running round with Wallace and Doyle). Evans and Rumbelow view dubiously indeed Nigel's account of interviewing the elderly retired policeman in the early 1920s, when he was "

home on leave from his job as a crime reporter on a newspaper in Shanghai." (Remember, Nigel was eighteen at the time.) "

According to Morland," write the authors:

Abberline said, "I cannot reveal anything except this--of course we knew who he was, one of the highest in the land." This alleged statement flies in the face of everything that Abberline had been reported to have reliably said about the case in the past. And why? The answer must be obvious. Morland had made the whole thing up, but the damage was done. This alleged statement by Abberline is now often quoted.

|

Another of Morland's besties?

J. Edgar Hoover (1895-1972) |

I think it's clear that when it comes to Nigel's divulgences many grains of salt must be taken. He also said he was on terms of friendship with American FBI Director

J. Edgar Hoover and he self-servingly dedicated the American edition of one of his Mrs. Pym books to the top G-Man. Perhaps had Nigel lived a little longer, until the claim that Hoover was a cross-dresser surfaced in 1993, he might have confirmed to his public that while living in the US in the 1920s he once had helped fit Hoover

into a dress.

Nigel Morland was a handsome man and he was said to be quite a charming raconteur. I can well believe it. It's clear on meeting the crime writer

Anthony Gilbert (aka Lucy Beatrice Malleson) in 1953 that he rather impressed her. (See my previous post.)

Of course the cynical will suspect that the of-a-certain-age "spinster" Gilbert was, shall we say,

susceptible, having unrequitedly fallen, according to catty

Christianna Brand, for Detection Club colleague

John Dickson Carr. However, there seems to be no question that Nigel had an exceptionally persuasive personality.

Nigel Morland may well have been a serial fibber, in some ways resembling, in a far more limited manner, sociopathic conman and mystery plagiarizer

Maurice Balk. Though unlike Balk, Nigel had some writing ability and his lies, if lies they were, did no harm to anyone personally, unless you count gulling people into buying his books by making the author seem more exciting than he actually was (though admittedly I can see how his treatment of Keith Chapman was hurtful to the latter man). Yet even if many of Nigel's truths were lies, he is still an intriguing person, in part precisely because of those lies. In life as in fiction brazen scallywaggery always seems to be more fascinating than bland goodness.