One intriguing aspect of these birds [ravens] is the collective noun used to describe a group of them: unkindness....there are several other collective nouns used to describe groups of ravens including conspiracy and treachery.

--Birdfact

It seems ravens then are tailor-made for a mystery novel, even without the association with Poe's famous gloomy poem, published 180 years ago this month. Although even more fitted are their relatives, crows, as in a murder of crows.

In a review of Sheila Radley's detective novel The Chief Inspector's' Daughter, Kate Jackson at Cross Examining Crime commented that she hasn't much liked detective fiction from the 1980s (was this before she was born) and that this book certainly did not change her opinion of the stuff. This led me to wonder whether the Eighties is the dull detective fiction decade?

At the time, anyway, Sheila Radley was seen as one of the promising up-and-comers of English crime fiction, but I think it's safe to say that her star has considerably dimmed. I myself, who was a teenager of the 1980s, reviewed this Radley mystery on my blog, along with the author's debut effort Death and the Maiden (actually published in the late 1970s), and of them I commented on how dated both books seemed.

Growing up in the 1980s I certainly recalled the so-called greed decade as a more vibrant time than was depicted in the The Chief Inspector's Daughter, but then I was a teenager, Radley a woman well into her fifties, almost old enough to be my grandmother.

|

| Women of the World unite! You have nothing to lose but your feminine mystique. A radical feminist notice from 1976, almost a decade before Ruth Rendell published Ravens. |

Of the novel I commented in my review: "All the stuff about women's lib seemed dated in a bad way and the big surprise, which wasn't as original in 1981 as the author seemed to think (and certainly isn't today), I could see coming a mile off."

I also noted that there was much hysteria over pot smoking as well as some really nasty anti-queer sentiments expressed by her cops of gay men, without any real signal of disapproval of this from the author (who herself was probably a lesbian).

Women cops are an anomaly, limited to serving coffee and consoling bereaved women and minding children. Luddite male cops view computers with hostility. Police forces are almost entirely lily-white. People make calls at pay phones, compose letters with typewriters and watch TV on boxy, chunky sets.

It all barely seems different from the 1970s, a decade I can remember as well. No one talks about music videos or new wave music, but I suppose 1981 was just a little shy of all that. If the author had portrayed any of this, however, there probably would have been sneering references to it all, like when PD James in one of her detective novels at the end of the decade made a withering, completely gratuitous reference to a gyrating English "pop star," whom, she, anyway, didn't deem sexy at all, mind you!

The truth is writers like Radley and James, both of whom who could well remember the Second World War, didn't really have a clue what young people in the Eighties (this means people my age) were like, judging from their writing. In James' case especially she was better when sticking to her middle-aged, white-collar, elitist white people, the kind with whom she was at complete comfort.

|

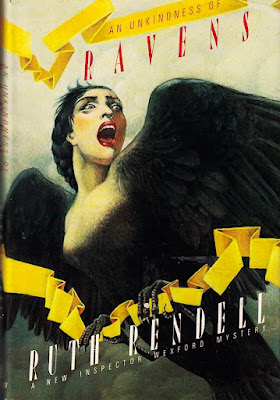

| the American first edition by Pantheon one of the most striking jackets of the 1980s in my estimation |

I don't believe there were any really significant changes in her Adam Dalgleish crime fiction between her masterpiece, Shroud for a Nightingale (1971), and her last AD mystery, The Private Patient, published the year the US elected its first (and only) black president in 2008, aside from her introduction into the series of cop Kate Miskin, which never really amounted to much because Kate remains rather an earnest, dull, goody two shoes. James was as out-of-touch, and hostile to, the modern era as ever Agatha Christie had been four decades earlier.

How did James's sister Crime Queen, Ruth Rendell, a self-proclaimed socialist, fare on this matter?

Rendell was a decade younger than James but only a couple of years younger than Radley. She too had vivid memories of the Second World War, when she had been an evacuee. But she strove to be rather more "with it," I think, in her books, taking a strong interest in morbid psychology, alternative sexualities and youth culture.

Rendell set one of her early Seventies Inspector Wexford detective novels at an outdoor rock festival and even provided rock music lyrics, composed by a cousin, for it. One might conceivably imagine Rendell at a commune in the Sixties wearing beads and puffing some marijuana, where with PD James that would be like imagining Queen Elizabeth snorting a coke line.

|

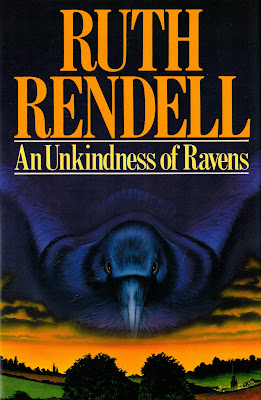

| the British first edition |

I was interested to go back and look at Rendell's seminal Eighties Wexford mystery, An Unkindness of Ravens, which, truth be told, I did not remember that favorably but honestly remembered very little about at all except that it is her so-called "feminism Wexford." From this point on Rendell organized her Wexford mysteries about some topical issue: feminism, nuclear energy, racism, environmentalism, spousal abuse, pedophilia, surrogacy and, in the first decade of the 21st century, female genital mutilation.

So how does Rendell handle feminism and youth culture in Ravens? Well, the answer is...somewhat ambiguously. Her attitude to young people, with their dyed hair and decayed morals, seems to be on the disapproving side, though at least Rendell takes notice of Eighties social trends.

Rendell hates television and "cathode culture" as Wexford calls it. Although the "boob tube" had been around for three decades television was more of a presence in our lives than ever in the Eighties, getting to the point where there was something on every hour of the day, even if it was just infomercials at three in the morning.

It often seems to come up here when I post about Rendell how she seems to have been a "man's woman," as several people, including myself, have put it, someone who identified with men frequently and could write from their point of view. She once said she made her series detective a man because the default social attitude was that "men are the people and we [women] are the others."

Sure, there were spinster detectives, most famously Miss Marple and Miss Silver, but though Miss Marple was enjoying her heyday when Rendell published her first Wexford in 1964, Miss Silver's creator, Patricia Wentworth, had passed away three years earlier (though Miss Silver remained in print). Police detectives were the thing, but even when Emma Lathen, say, created an amateur detective, John Putnam Thatcher, it was a man.

Over 1959-66, PD James, Patricia Moyes, Sara Woods, Catherine Aird and Rendell all created male detectives to headline their series. (Anne Morice in 1970 was a little more daring here, with her actress amatuer sleuth Tessa Crichton.) Women investigators were much more often found in domestic suspense fiction, which Rendell also wrote for a time. Her first suspense novel, Vanity Dies Hard, she later professed to despise, speaking contemptuously of it as I recollect as a "brave little woman" novel. (It's definitely written according to women's magazine serial conventions, but I rather liked it.)

However, when Rendell created a female cop, Hannah Goldsmith, she promptly became the most hated character in the Wexford canon I think, a walking model of "political correctness," an ideological construct coined by the Right in the 1980s which Rendell obviously bought into and which she clearly hated. (The term has since been replaced by the politically correct Right with "wokeness.")

Of course just because a woman has a male detective in her mysteries, it doesn't mean she is an anti-woman arch traditionalist. Wexford, in my view, reflects the author herself and definitely comes off, certainly by the Seventies, as a model liberal Englishman of the day. (Even his reactionary underling, Mike Burden, thaws somewhat after he marries his liberal second wife.) So what happens in Ravens when Wexford confronts a youthful radical Marxist feminist cell in his very own town of Kingsmarkham?

|

| I Want My MTV! The blondish kid could have been me but parents watched a lot of television programs too. |

Rendell published Ravens in 1985. It was the mystery author's thirteenth Wexford detective novel, and the first one to take place entirely in England in seven years, since A Sleeping Life (1978). (There were two partial travelogue mysteries, Put on by Cunning and Speaker of Mandarin, in the interim.)

The formal mystery plot of the book concerns Wexford's and Burden's investigation into the disappearance of Rodney Williams, an actual neighbor of Reg and his wifely "stay-at-home" spouse Dora. An apparent model family man, married with two children, Rod, it turns out, is (was?) in reality a cheating bigamist with another, younger wife and a daughter in the same area. So much for Eighties "family values"!

Rod's Wife No. 1, the ironically named Joy, is a miserable, bored woman who spends most of her day compulsively watching junk television programs and popping a prescription pill or two. She obviously didn't care about her husband, who was absent much of the time (he had two households to keep), nor does she like her teenage daughter, but she lavishes attention on her son, who is away at college. The teenage daughter in turn evinces no concern with her parents' problems, her absorbing interest being her upcoming college entrance examinations. (She wants to be a doctor.)

Rod's Wife No. 2, Wendy Williams (!), unlike Joy has a salaried job, but she is mostly interested in being a womanly woman and is very house proud and conventionally feminine indeed. Neither one has any interest in feminism or rethinking relations between the sexes, despite the fact that both had been duped by a designing male.

|

| the American first edition drawing on an image actually described in the novel |

Joy's daughter Sara, however, belongs to a militant feminist group with around 500 members, most of them high school girls like herself, called ARRIA (Action for the Radical Reform of Intersexual Attitudes), whose symbols are a raven and a harpyish figure, half-woman, half-bird. To say that ARRIA is anti-male is something of an understatement. Over the course of the novel there are several knife attacks on men by women assailants--could this be ARRIA terrorism? Was Rodney Williams one of their victims?

As a mystery Ravens on a second reading seemed to me rather better than I remembered. It's shorter than her books were soon to become, around 80,000 words, which generally is, I think, all to the good in a detective novel.

It actually reminded quite a lot of a Freeman Wills Crofts detective novel, oddly enough. It seems one of her more procedural novels and a great deal of time is devoted to the investigation of typewriters! This took me right back to the Twenties, another link with the past rather than the future, with typewriters in the Eighties soon to be made obsolete by personal computers.

Rendell actually manages a good twist on what for many pages seems a rather obvious outcome. I was fooled, and I had read the book before! Best of all, the twist is fairly clued. If you don't see it ahead of time, like me, you will think, I should have seen that! At this stage of her career Rendell was still interested in writing detective novels in the classic puzzle form.

|

| Was An Unkindness of Ravens the last of the great typewriter identification mysteries? |

As a social document, however, this mystery has generated hostile attention from modern-day internet reviewers at goodreads, some of whom have denounced the novel in strong terms as not only anti-feminist but anti-woman (or is that the same thing). Even the contemporary Kirkus review back in September 1985, which was probably written by a man, criticized "often-dated feminist themes" in the book, along with an overly Freudian solution. On the other hand, the New Yorker deemed the novel a "suspense mystery of the highest order" that put "most of its like to shame" and the New York Times proclaimed it as "exciting as anything Ruth Rendell has written," revealing the author's "usual mastery of middle-class folkways.

One of the criticized elements in the book is the subplot about Mike Burden's second wife becoming hysterically upset when she finds out her baby will be a girl. I think this is a bit of a misread hoever. Jenny Burden herself is a liberal and as I understand her anxiety it's based on the notion that women cannot get a fair shake in life in a male world. Yes, it's a defeatist attitude, but it's not really an anti-feminist one. It still sees men as a problem, perhaps THE problem.

Really Jenny's attitude is akin to those people concerned about climate change who don't want to have children because they there is no future for anyone in a sadly doomed world. Additionally I know Rendell was quite interested in in postpartum depression (perhaps she went through it herself with her son in the Fifties), and Jenny's behavior seems related to the mental stress of her pregnancy. .

|

| Ruth Rendell in 1985 Highly sinister! |

For the most part, however, Rendell does portray women unsympathetically, but the wives she actually dings for being very traditionalist "wifey" women. ARRIA would make the same criticisms of these two ladies as having been brainwashed by white hegemonic masculinity as the jargon goes. Many years later Rendell said that a woman has to be feminist to some degree, "unless she is sleeping."

On the other hand, Rendell obviously doesn't like the leftist jargon either. It's a mainstream liberal perspective, I would say, not necessarily anti-woman per se. Unfortunately I can't really talk about the outcome of the plot from an ideological perspective, cause, you know, spoilers; but I have to say that looked at purely as a technical construction the whole thing is pretty damn clever.

In an English newspaper interview in 1985, Rendell said that in her mysteries she liked to have "one climax, then a drop, another climax, then a twist right at the end, one last surprise--if possible in the last paragraph--so you sit right back and say "Wow, that's amazing."

I'm not exactly sure how many, ahem, climaxes Ravens experiences, but it does indeed have a fine late twist, along with an ironic little surprise in the last paragraph. This is the mark of a remarkable mystery craftswoman who takes plotting construction seriously.

Good review! Nick Fuller recommended this as one of the best Rendell's, and I've been meaning to read it for a while.

ReplyDeleteAnd what in the world was up with that last picture?

She looks like she just poisoned someone's tea, doesn't she? Some of her pics definitely played up her "sinister" look. Good look for a Crime Queen.

DeleteI think pretty much all her Wexfords up to this point are good detective novels, one exception being A Guilty Thing Surprised, which I reviewed here.

Delete