"...he's being deliberately mysterious."

"Well, so are you."

"It's sex, Leo....Sex! The unbreakable taboo!"

"...he wants no traffic with sweeping reform."

"Good for him!"

"I am glad to hear you say so."

"Crime and the sensational!...We have a sufficiency of both in New Orleans."

"How the hell...can a man be shot through the head at the wheel of an automobile when there's nobody there to do it?"

--From The Ghosts' High Noon, by John Dickson Carr

I.

|

| Mystery Girls |

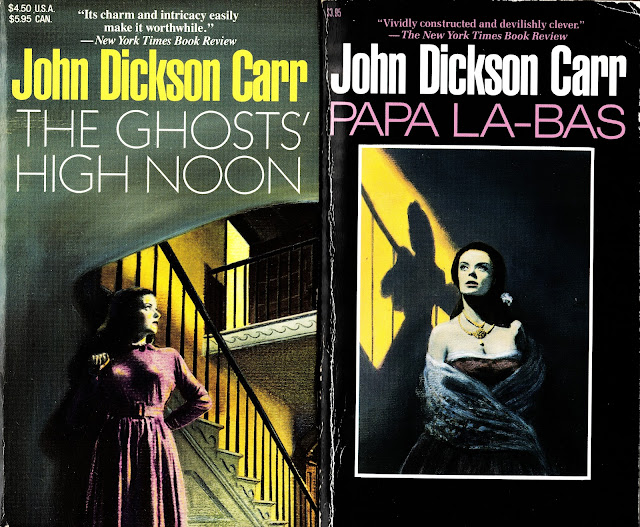

Inspired by some recent sites I saw in Memphis I decided to take a look at one of the last mysteries John Dickson Carr ever wrote: The Ghosts' High Noon, which is set in New Orleans in 1912.

Memphis you may know is about 400 miles up the Mississippi River from New Orleans and is the biggest city on the river between the Crescent City and St. Louis. A few weeks ago in Midtown I came across a short street called Carr Avenue. I like to imagine it was named for John Dickson Carr, even though sadly that is not the case. However most of the homes on it were built around 1912, many of them New Orleans style shotgun houses for streetcar workers. Walking down it, it's like being back in 1912. You can imagine you are in a period Carr miracle mystery, with an automobile incredibly entering the avenue, then disappearing before reaching the end of it.

As Carr fans will know the locked room maestro in his writing turned increasingly to historical mysteries with the publication of The Bride of Newgate in 1950, when he was 44 years old. Over the next 22 years he published only five contemporary Dr. Fell detective novels, these in two brief spurts over 1958-60 and 1965-67, while his Sir Henry Merrivale detective novels petered out with a trio of volumes published over 1950-53. Compared to these eight books, he published fully a dozen historical mystery novels over this two decade period.

Carr suffered a significantly debilitating stroke in 1962 after publishing the historical mystery The Demoniacs, and, while his books had already suffered something of a decline in the 1950s, their quality "fell" more afterward. Like Agatha Christie an annual producer of a mystery tome (a Carr for Christmas), Carr could only put together a collection of previously published short stories for his 1963 outing and in 1964 he revised an older obscure historical mystery from the Thirties for publication. It was not until 1965, three years after the publication of The Demoniacs, that he was able to produce an original volume, The House at Satan's Elbow, in 1965.

While in my opinion Elbow, a Dr. Fell mystery, is the best of the seven mysteries Carr published between 1965 and 1972, the drop-off in writing quality from earlier Fell tales, even In Spite of Thunder (1960), is definitely discernible. Anyone who reads my review of Thunder will see I didn't like it much at all, and the truth is I actually enjoyed Elbow more for perhaps sentimental reasons of my own; but I'll readily concede it's a more lumbering, listless narrative than what is found in his earlier tales. However, compared to the final pair of Fell mysteries, Panic in Box C and Dark of the Moon, which followed over the next two years, it almost seems like a masterpiece.

Panic and Moon share the general problems from which Carr's mysteries had been suffering for some time, elevated to the nth degree: too much talk, too much mysteriousness, irritating, adolescent characters who frequently act like idiots. Despite his insistence that he was one of the pillars of the true, simon-pure detective novel, Carr for some time had been littering his mysteries with as much irrelevant incident as any hard-boiled detective novel. Raymond Chandler may have advised mystery writers that when stumped they should have have a man come through the door with a gun, but with Carr it is more a maddening woman with a silly, overblown secret or a load of some supernatural folderal.

In his heyday, Carr was able effectively to incorporate such business into a mystery: novels like The Burning Court (1937), The Crooked Hinge (1938) and He Who Whispers (1946) are compelling and atmospheric genre masterpieces. But even before his stroke Carr was fumbling the ball, as it were. I'll quote myself in my review of In Spite of Thunder:

Again, for someone who professed to hate hard-boiled mysteries, Carr evidently felt that in his story he had to pile on incident (shouting and screaming if not actual fisticuffs and sex). If "Humdrum" mysteries can err on the side of being too cerebral, Carr's books at this time can err on the side of being too emotional. Carr is always telling us, as if we can't tell for ourselves from all the exclamation points, that the emotional temperature in the room is going through the roof, etc. Yes, there's a very heavy use of exclamation points (!), what with characters shouting and roaring and crying "Yes!" and "No!" You just want everyone to calm the f--- down already.

One of Carr's most irritating quirks is to introduce the woman who is acting mysteriously for what turns out to be a remarkably insufficient reason. The worst of these women is actually Audrey Page in In Spite of Thunder:

Audrey is a stock character too, and not just because she's a young and sexually attractive "heroine" and love interest. There is nothing else to her personality besides that she's a maddening ditz. She's there simply to bewitch and frustrate, to tantalize and tease, the hero, Brian, through a series of annoyingly capricious actions. This sort of thing became a given in Carr novels, but the problem here is that Audrey really is exceptionally irksome even by Carr's standard of irksome women. "I've been very silly, you know, and I've behaved about as stupidly as anyone could behave," she admits to Brian. Yes, indeed you have, Audrey! But does that stop her from continuing to behave that way? As a Carr character would say: "No, no, a thousand times no!"

We learn that Audrey came to Geneva simply to get Brian Innes to chase after her, because, you know, she simply couldn't tell Brian she loved him, I guess. It's interesting that Carr expressed hatred for hard-boiled crime fiction, because characters like Audrey behave a lot like femmes fatales in those books, existing solely to bedevil the hero, though ultimately Carr's young "charmers" usually prove to be good girls after all, just rather maddeningly flighty and childish. She "began to slap at the table like a woman in a frenzy or a child in a tantrum," writes Carr of Audrey at one point, mentally likening women to children in an unflattering comparison.

All Brian and Audrey do the whole book (until the very end) is bicker. This "battle of the sexes" motif is a prominent feature in later Carr (indeed it features in earlier Carr too), but it's so damn obtrusive in this novel. It's hard to understand just why these two love each other--they certainly don't seem to like each other, What they really need is not a murder investigation but a relationship counselor:

"But can't you s-say you love me," Audrey cried out at him, "without swearing at me and looking as though you wanted to strangle me?"

"No I can't. That's how you affect people."

"All right. I don't mind; I love it."

Brian tells Audrey, in the anachronistically stilted language characters in which male characters speak in this book, "You're a female devil, a succubus of near-thirty masquerading as nineteen....I've been looking for you my whole life." What a charmer! I guess Audrey, who seems to have masochistic tendencies, loved that endearment as well.

Audrey is the most tiresome of these she-witch Carr characters, but they pop up over and over again. We'll get to more in the books I'm going to talk about below.

But Carr has all sorts of tiresome quirks in the later books, all of which have been noted by Douglas G. Greene in his masterful Carr biography, The Man Who Explained Miracles, published thirty years ago this year. There are the radio-script style stage directions, a carry-over from his work in that field in the Forties and Fifties. Carr was probably the greatest radio mystery writer who ever lived, even better than Ellery Queen and Anthony Boucher, but what worked in radio doesn't work in novels.

In his narrative Carr will include these long descriptions of house layouts which read like radio stage directions; whether put in his characters' mouths or in the third person narrative, it's tedious writing indeed. Then he will stop a chapter with some sort of contrived climax and then open the next chapter several hours later with characters talking about what happened in the intervening period, promptly deflating his climax.

But there is so much talk generally it's hard ever for Carr to sustain the excitement he is going for. It doesn't help that the characters speak so anachronistically and floridly and oracularly. Carr does a thing I call "dashing," where he has a character about to tell something pertinent to the mystery, only promptly to interrupt him or herself with some sidetrack, like this:

"But you simply must hear this minute what I finally have come to realize, the precious golden key to the mystery that we all in our varying fumbling ways have been striving so desperately to grasp in order to unlock this devilish puzzle box of a conundrum! The reason no footprints were left in the dust in the armaments room room of the castle was--"

"Is that the tea kettle I hear whistling?"

Then five chapters later, if we're lucky, this person, if they aren't aren't murdered in the meantime, may get around to telling what they know.

All of these faults are present in the earlier Fell mysteries In Spite of Thunder and The Dead Man's Knock, but Panic in Box C and Dark of the Moon (and The House at Satan's Elbow to a lesser extent) take these and add some more. At least in the earlier books Carr was able to generate a sort of synthetic excitement, even if he was trying much too hard. These later books are just dull, the characters tiresomely verbose and silly, the narratives prolix, the climaxes duds. The characters behave like juveniles (or immature college students), even calling each other by silly nicknames. In Dark of the Moon Dr. Fell gets called magister, maestro, gargantua, Torquemada and other terms I can't recall. It just makes me want to tear my hair out.

Part of the problem was Carr just could not believably portray the contemporary scene, with which he himself was completely out of sorts. Increasingly he put his heroes' ages in their thirties or even forties, while making his heroines shy of thirty (though they usually "look nineteen"); yet none of them, however old, sound like actual people who could have lived in the mod era.

Happily Carr finally dropped Dr. Fell and the modern world after Moon and his last four novels--Papa La-bas, The Ghosts' High Noon, Deadly Hall and The Hungry Goblin--were set in the past, two in the Victorian era and two in 1912 and 1927 respectively. Are they any better? I haven't read The Hungry Goblin, which the estate oddly has repressed from republication, apparently on the grounds that it is such a terrible book (could it really be worse than Dark of the Moon?), but I would say that the New Orleans trilogy of novels is at least a little better than the final two Fells.

II.

The first of these novels, Papa La-bas, launched Carr's New Orleans trilogy of mystery novels. It's an improvement over Panic and Moon, but it's still not actually good. It exhibits all of the problems of his later books, if somewhat less conspicuously than the previous two.

|

| Delphine LaLaurie (colorized) |

There was actually material here to make a good book, had the younger Carr written it. Set in 1858, shortly before the outbreak of the American Civil War (or War Between the States as Carr, like Raymond Chandler, always called it), the novel draws on the notorious real life case of Delphine LaLaurie, a New Orleans socialite believed to have tortured and murdered many of her slaves.

An infuriated city mob actually invaded and razed her mansion in 1834, forcing her to flee the state and the country and settle in Paris, where she died fifteen years later. In Carr's novel it appears fairly early on that LaLaurie's adopted son--a character invented by the author--has returned to New Orleans to avenge himself on the mob's ringleaders, all of whom are socially prominent men (in Carr's handling).

As stated, this is good material for a mystery melodrama, but sadly none of it ever really takes flight, being held down by the prolix, tedious narrative. Carr introduces voodoo--or more accurately rumors of voodoo--but this never really goes anywhere, despite much mention being made of real life New Orleans "Voodoo Queen" Marie Laveau.

Very quickly the book descends into characters dully orating at each other, including the book's nominal amateur detective, historically prominent real-life southern politician Judah Benjamin (nicknamed "Benjie" in the book). The fictional character Isabelle de Sancerre, a wealthy slave owning matron, goes on and on to similarly fictional English (actually Scottish) consul Richard "Dick" Macrae about various New Orleans legends. Even Carr refers to this lady in the book's Notes for the Curious as "that tireless talker."

Then as love interests there are two young women--Margot de Sancerre, Isabelle's willful southern belle daughter, and Ursula Ede, her steadfast second banana friend (what I call in Carr's books the brunette one and the blonde one)--both of whom are behaving maddeningly mysteriously.

There's not much nicknaming in this one, though Ursula insists on calling Dick "Quentin" for some reason. There are a couple of stock English comic cockney characters who vexsomely speak in ponderously overdrawn dialect. The murder method in the killing of Judge Rutherford (a cameo character who exists only to be killed) Carr presumably cribbed from a Dorothy L. Sayers novel, while the central concealment device for the murderer he probably derived from a certain opus by Cornell Woolrich, an author with whom he had qualities in common. I think it becomes screamingly obvious who the murderer is around page 100, yet unrelentingly the book goes on.

All in all it's another tired work by Carr. One thing this time around I noticed (it's my second read) that I thought was kind of funny, however: Dick has two pals, Tom Clayton and Harry Ludlow, whom he goes to a "quadroon ball" with; and it finally occurred to me this time that together they are "Tom, Dick and Harry."

Speaking of quadroons (people one-fourth black), Carr basically seems to view slavery as more or less on par with the old English class system of masters and servants. (It's how southern slave-holding "aristocrats" liked to view themselves, however self-deceivingly.) This doesn't add one bit to the charm of the book, to say the least. When a character casually mentions having won himself a slave in a card game, no one bats an eyelash. The fundamental inhumanity of it all Carr doesn't seem to get.

At one point our good English consul, the "hero" of the story, so lectures his underling Harry when he thinks (wrongly) that Harry is about to object to the morality of quadroon balls, which are attended by comely free "mulatto" women in hopes of finding wealthy white men to make mistresses of them:

"The situation exists, and must be faced; let's have no moralizing or cant!"

|

| "The Quadroon" 1911 poem by black reformer W.E.B Du Bois |

Well, isn't that special? Actually it's quite clear that all three men are rather sexually titillated by these balls. Of course they are all sexists as well, thinking spanking is a great way of disciplining willful, headstrong women like Margot, who shockingly shows up at the ball too, even though she is not of mixed race. Conversely, little problem apparently is seen with beautiful women having essentially to sell themselves sexually because they have in them some drops of "black blood." The situation, according to Dick, must be faced, but it need not be faced and corrected, apparently. Tell that to W.E.B. Du Bois. (See pic to left.)

Reformers, after all, are just a bunch of self-righteous sermonizers, right? Nothing more than a sourfaced pack of puritanical blue noses and spoilsports.

Did Carr see all moral stances as cant (i.e., sanctimonious lecturing), or just the ones he himself didn't care about personally? What about, say, concern over genocide or pedophilia? (On the latter matter see below.) Elsewhere Dick Macrae sneeringly refers to objecting to slavery as singing "pious hymns" and Harry Ludlow announces: "I can't be as shocked by slavery as people at home think I ought to be."

Judah Benjamin, a real-life character whom Carr clearly admires, when queried about his convictions on the subject, states: "I do not say slavery is wrong, as I do not say any property owning is wrong." In real life Carr like Benjie was a great defender of the rights of property owners and he thunderously damned British postwar taxation as iniquitous oppression. Perhaps he was right about this. But not to appreciate that human property belongs in a different category from mere inanimate objects is what seems truly iniquitous to me. To take away someone's independent personhood through enslavement strikes me as one of the worst sins one can commit.

|

| Judah Benjamin a proslavery Jewish US senator from Louisiana at the time Papa La-bas takes place |

Doug Greene in his Carr biography states that social systems per se did not trouble Carr, though he did think one had an obligation to behave "honorably" within them: i.e., masters should not mistreat servants, freed or enslaved, like Delphine LaLaurie allegedly did. There's a gambler character who behaves badly to Dick's free black servants and is upbraided by Dick for doing so.

Yet surely sometimes social systems are so bad that they ought to be drastically reformed; individual acts of kindness don't do nearly enough to mitigate the overall evil of the system in place. But Carr and the characters with whom he sympathizes in his books are all self-proclaimed "conservatives" who instinctively oppose social reform as dangerously "radical."

Carr himself, like his dearest enemy Raymond Chandler, professed to take the part of the Confederacy in the American Civil War, likening southerners to his beloved English cavaliers; and in his later years he left England to settle in Greenville, South Carolina, of all places, where he praised the southern states as bedrocks of conservatism and sarcastically dismissed concerns about civil rights as lurid exaggerations. (My family moved to Alabama the same year but my parents never deluded themselves like Carr about the reality of the region's endemic racism.)

III.

Compared to Papa La-bas, The Ghosts' High Noon is actually something of an improvement, and not just because we aren't having slavery thrown in our faces. (In slavery's place we get something else odious and objectionable thrown in our faces; see below.) Carr actually repeats some of the plot points from Papa, but he at least comes up, this time around, with a pretty good and apparently original "impossible" murder.

|

| homes along Bayou Saint John, scene of crime in The Ghosts' High Noon |

It's 1912 and our hero, James "Jim" Blake, is an admired journalist turned successful spy novelist. His recently published debut novel, a bestseller, is The Count of Monte Carlo. Carr here alludes, accurately enough, to the English crime writer E. Phillips Oppenheim, who had already become a hugely popular author in the United States with his tales of international intrigue in Monte Carlo and other swanky European locales.

In New York Jim is asked by George Brinton McClellan Harvey, a real life prominent conservative Democrat (soon to become a Republican) and editor of Harper's Weekly, to report on rumors of political intrigue in a congressional race in New Orleans concerning Democratic nominee Jim Clayton "Clay" Blake. "The underground wire has it that some enemy is out to ruin him," Harvey explains.

|

| Carr's kind of guy prominent anti-progressive George Harvey |

Clay, Harvey tells Jim, is "like most southerners...as conservative as you are." (Harvey means white southerners of course.) Jim himself confirms, without explanation: "I'm a conservative, even a reactionary...I distrust progressives and hate reformers."

113 years ago near the height of the Progressive Era, there was much, one might believe, that needed reforming, such as the franchise (women could not vote) and racist Jim Crow laws, but not so to our Jim Blake, who, conveniently for himself, doesn't actually like talking about politics. If he did, he might have to articulate defenses of some of his heinous positions!

But anyway off goes Jim by train to New Orleans, with a stop at Washington, D.C., which allows Carr to indulge himself in some nostalgia about streetcars and such. (He lived in DC as a small boy when his father briefly served as a US congressman--a Democrat!)

Chunks of exposition have already been served up to Jim and the reader by George Harvey; and in DC yet more is ladled out by Charley Emerson, an old bachelor whose interests, sounding a lot like Carr, are "old books and toy trains." Then it's off to New Orleans!

Along the way on his New York trip Jim literally twice runs into fetching, fair-haired Jill Matthews, for whom in Carr tradition he immediately falls emotionally. Yes, it's another one of Carr's age-mismatched romances, Jim being thirty-five and "not ill-looking in a strongly Anglo-Saxon way [?]" and Jill being twenty-seven and "very pretty" with "admirable body proportions" and "a sense of humor struggling through" her delectable "pink mouth." Very soon Jim is rather familiarly calling Jill "my sugar-candy witch," one of those weird anachronistic endearments (even for 1912 I suspect) for which Carr had a penchant. Indeed, this phrase seems unique to Carr. Women also get called "wench" a lot in his books.

|

| suffragist Aimee Hutchinson was fired from her teaching job at a Catholic school for attending a suffrage parade in 1912, the same year as The Ghost' High Noon. (See here.) Carr's hero in that novel is a self-described reactionary who firmly opposes sweeping social reform. |

Jill, however, justifies the endearment (?) when she maddeningly keeps running away throughout much of the book. When she explains her behavior much later on, her explanation hardly seems sufficient. Unfortunately this not very compelling subsidiary mystery around vanishing Jill swallows much of this book, like the proverbial gnat swallowing the whale.

There is eventually a "miracle" murder but it's not until around page 200 in a 300 page book that Carr really gets serious with it. There's also the supposed "miracle" mystery of the person who knocked on the door of the train compartment where Jim, Jill, and a New Orleans bon vivant friend of Jim's, Leo Shepley, are discussing the Clay Blake matter and then vanished, but this little mystery, never very compelling in the first place, fizzles miserably. At least it doesn't take up as much of the book as the matter of Jill's Jilting Behavior.

Jim finally gets to New Orleans on page 84 and the murder of Leo Shepley takes place about fifty pages later. Witnesses, including Jim and Jill, see him drive down the Bayou St. John road in his snazzy red Mercer Raceabout into a barn-like shed on the grounds of a mansion and then hear him apparently shoot himself. But, wait, where's the gun?! Could it be murder?!

I still like miracle problems (Carr at his best is an abiding delight in this regard) and this was an enjoyable one, much better than the shenanigans in Papa La-bas, where there are also a surfeit of mysteries, including Margot's vanishing from a moving carriage, and not a single one of them compelling.

|

| "The Mercer Raceabout is considered the most prized original American sports car. Known for its enhanced design, magnificent handling and high speed, these cars won five of six races they entered in 1911. Mercers came with the unheard of guarantee that each Raceabout would achieve a minimum of seventy miles per hour without modification on public roads." See Heritage Museum and Gardens |

I found the period atmosphere in Noon enjoyable enough, though many of the characters in the book sound more like callow 1920s college students (like Carr, now 63, had been four decades earlier) rather than Edwardian adults. This is how Jim and Leo greet each other on the train:

|

| New Orleans' Hotel Grunewald setting for a late tete-a-tete between Jim and Jill |

"Leo, you old bastard, how are you?"

"Jim, you unregenerate son-of-a-bitch, have you visited any good whorehouses recently?"

Later this boyish pair sits down in a compartment with Jill, have drinks and chat about whores and homosexuals. Jill is Carr's perfect type of girl, the kind that looks prim and proper on the outside, but is really way into sex underneath (even wanton), pally with the boys and sympathetic to all of her beau's charmingly masculine foibles.

She's the kind of girl you can throw up on at the college football game when you're drunk out of your mind and she will gamely smile and wipe your vomit off her dress with a handkerchief (or more likely several of them).

"I want you to do mad things," Jill admiringly tells Jim. "I love it!" Remembering that she's living in the Edwardian era, she won't smoke in public, however, at least until late in the book.

|

| Jim and Jill share a romantic rendezvous at The Cave, a fanciful grotto-like dining room in the Grunewald Hotel |

In a good number of later Carrs, illicit sex between older men and younger women (or "girls" as they are called) is a central interest. And of course in the case of Ghosts' High Noon the setting is New Orleans, which had an infamous red-light district known as Storyville, so Carr has come to the right place! I don't know of any reviews explicitly mentioning this (or Doug's bio either) but the illicit sex in this one takes place between adult men and what Carr refers to as "pubescent girls" around the ages of 12 or 13, which raises the "ick" factor considerably.

Worse yet, Carr adopts the same attitude to child prostitution that he does to the quadroon balls: judiciously neutral, if one wants to be generous, though one might more accurately say pruriently interested. Despite dwelling on this subject at considerable length in his novel, in his Notes for the Curious Carr himself completely avoids the subject of Storyville child prostitution. Did the subject spring entirely from his own mind?

|

| Storyville prostitute photographed by E. J. Bellocq |

The Green Capsule in its review of the novel very delicately and disapprovingly approaches this matter: "There is a particularly vile subject needlessly included in the story, and I'm not even going to mention what it is. That Carr treats it with a "men will be men" attitude is beyond me, and I could imagine some readers just shutting the book."

Well, I'm going to dare to discuss this "vile subject" in depth below, so take heed. You can draw your own conclusions as to what it says about the author. Carr seems to intimate that a sexual predilection for young girls, at least when the girls are ostensibly "willing" participants, is rather less aberrant than homosexuality.

This take first comes up when Dick, Leo and Jill are discussing the Clay Blake affair. The rumors about Clay Blake concern "something abnormal or unnatural," speculates Jim. "The slightest suggestion of homosexuality, for example...." This speculation provokes an infuriated Leo to smite his fist on the table, rattling the glasses and china.

"What kind of friends do you think I have, for God's sake?" Leo roars. "No, Jim, I won't hear that for a minute! It's nothing at all abnormal or unnatural, at least in the way you mean."

So Leo objects to Jim suggesting he might have gay friends, but pedophiles (or near-pedophiles) are a-ok, apparently. Later on in New Orleans Jim discusses with a couple of Crescent City pressmen the criminal case of Etienne Deschamps, a New Orleans dentist who in 1892 was tried and executed at the age of 62 for the murder three years earlier, when he was 59, of 13-year-old Juliette Deitsh. (She was actually, contra Jim/Carr, 12.) Dr. Deschamps had a habit of chloroforming and sexually assaulting Julia, but one day he administered too much chloroform to her and she died.

|

| Jerry Lee Lewis and his "half-grown nymph" Myra |

Jim declares of young Juliette that Deschamps "made the girl his mistress" and that "she seems to have entered heartily into the affair and had all the essential attributes of a woman." Pardon the canting and pious hymning here, but isn't this stance rather on the grotesque side?

Okay, I'll allow that in Mississippi in 1957 22-year-old rock singer Jerry Lee Lewis married a 13-year-old cousin and that under the English common law of rape the age of consent was set at twelve or even ten, meaning that if a man had sex with a twelve-year-old, the girl was compelled to prove that she had not consented to her physical violation in order for the act to be deemed rape. So Carr's attitude is actually a traditional one and we all know Carr loved tradition.

Still Carr was writing in 1969 not 1669, for God's sake. Back in the 1950s Jerry Lee Lewis' career suffered a significant setback over his marriage. (It didn't help that the couple were cousins as well.)

On Carr goes about this subject throughout this book. Later Jim visits Flossie Yates, a New Orleans madam who specializes in procuring young girls for her clients, what Carr calls "pubescent girls," presumably meaning they have "all the essential attributes of a woman." Flossie talks of two such girls, Sue, who is 14, and Billie Jean (had Michael Jackson read this book?), who is not much over 12. Billie Jean, she declares, "is exceptionally mature for her years." She calls her charming girls "half-grown nymphs."

Other characters, when this topic comes up (which it does frequently), call them "the near nubile" and refer to Flossie's "stable of underage ones" and "the joys of the pubescent" and "men with a passion for half-formed bodies and the caresses of the immature." Clay Blake explains that he was "accused of spending my nights in orgies with girls twelve or thirteen years old. Don't look so shocked, any of you." He adds this even though, Carr pointedly tells us, "in fact nobody did look shocked; the women merely looked thoughtful." Women in Carr's books strive hard to look proper, but under the skin, they are, like the colonel's lady one imagines, greatly interested, perhaps even more than men, in sex of all stripes.

.jpg) |

| Storyville |

Let me make clear that I'm not suggesting that Carr was, like occasional mystery writer Eden Phillpotts. a secret pedophile. Actually, to be accurate, I have discovered that the technically accurate term for what Carr is describing, a person attracted to pubescent children (as opposed to pre-pubescent children), is hebephile. I'm not even saying Carr was one of those either, like those fictional clients of Sue and Billie Jean in The Ghosts' High Noon. Yet to me a lot of the notions expressed about sex in Carr's books come off as juvenile, sexist, prurient and occasionally disgusting.

Others have agreed. "Sex amateurish and repulsive at the same time," wrote Humdrum mystery devotee Jacques Barzun in his and Wendell Hertig Taylor's tome A Catalogue of Crime of Carr's 1949 detective novel Below Suspicion, though ironically The Ghosts' High Noon was one of the few Carrs Barzun actually liked. "One of his sober and sustained efforts," he declares. (Barzun doesn't mention the child prostitution either.) Of Noon specifically a nonplussed Keith Boynton at Goodreads avowed, "the story's cavalier attitude towards pedophilia is pretty damn jarring."

Over and over Carr's later novels feature older men attracted to much younger women, often women who "look about nineteen." Then there's this very sexualized and smitten description of Lady Brace in the The Cavalier's Cup (1953), who enticingly looks for all the world like jailbait, though she actually isn't. Evidently a real dream girl fantasy in high heels:

|

| Actress and "small girl" Shirley Temple receiving a corsage on her fifteenth birthday in 1943. Like Carr's Lady Brace, her hair "fell to her shoulders and curled out a little in artless, young-girl fashion." Six years earlier, when Temple was only nine years old, author Graham Greene had scandalously asserted in a film review that Temple's "admirers" consisted of "middle-aged men and clergymen" who were attracted to her "well-shaped and desirable little body." |

The very pretty girl who entered [Chief Inspector Masters'] office, he would have sworn at a first quick glance, could not have been more than fifteen years old, despite her modish clothes.

First of all, even wearing her heels she was only five feet tall. Her soft and silky light-brown hair fell to her shoulders and curled out a little in artless, young-girl fashion....

[...]

"I'm awfully sorry to intrude, Chief Inspector said the small girl, in a warm and sweet voice as feminine as herself. "But do you mind if I sit down?"

[...]

....her figure...was a fine one....for all its innocent and demure appearance, her expression held a quality of the impish. The small girl...used her rather heavy-lidded gray eyes and pink lips in a way which would have inspired speculation in any man who had been married for fewer years than Chief Inspector Humphrey Masters.

1953 was the time, I have speculated, that Carr, a happily married yet perpetually dissatisfied man who engaged in a number of extra-marital affairs or assignations, was having a midlife crisis. (He was 47.) In his books and his life in his later years he seems to have been obsessed with recovering the unrecoverable past, the world's and his own, wanting desperately to relive the joys of his lost youth, when life had more zest.

|

| All the essential attributes of a woman? Brooke Shields as a child prostitute in the 1978 film Pretty Baby |

Back to The Ghosts' High Noon, late in the novel police detective Zack Trowbridge, who calls Jim Franz Joseph (don't ask), admits that the police know all about Flossie Yates and her underage girl harem. Why isn't she prosecuted? It seems that "if the girls are proved professionals [!] it's hard to touch anybody." So these decidedly pro young girls remain readily available to to gratify the lusts of "anybody who's got the dough." Storyville, it seems, is a perfect island of depravity, rather like the late Mr. Epstein's literal one.

(The red light district was finally shut down in 1917 when the US entered World War One and established a military base in New Orleans. The government emphatically did not want the troops dallying with Storyville whores. My then twenty-one-year-old paternal grandfather, incidentally, was stationed down there at the time.)

Interestingly five years after the appearance of The Ghosts' High Noon, Louisiana writer Al Rose published Storyville, a history of New Orleans' red light district which included an account of a young girl who was forced into prostitution by her own mother. The account in turn served as the inspiration for the 1978 movie Pretty Baby, which starred actual twelve-year-old model and actress Brooke Shields as the titular child prostitute. Carr died the year before the release of this flick at age 71, so he never got see how his then forgotten novel anticipated one of the most controversial films of the Seventies. To me all this adds unexpected piquancy to The Ghosts' High Noon, however problematic Carr's take on the subject of child prostitution is.

.jpg)