|

| Mary Stewart (1916-2014) |

Symons, however, does not go unmentioned in a letter which Mary Stewart penned, five years after the publication of Bloody Murder, on November 28, 1977. Stewart's letter was written in reply to one from John McAleer, a Boston College English professor and biographer of the late American mystery writer Rex Stout.

An evidently plaintive McAleer had written to Stewart concerning a Symons' review of McAleer's biography of Stout, which had been published in the New York Times Book Review on November 13. Symons' assessment of the book was, to out it charitably, mixed; and it also managed to get in some rather dismissive asides against McAleer's highly esteemed subject, who had passed away at the age of eighty-eight two years earlier.

"No livelier man (than Stout) been the subject of a duller book," pronounced Symons bluntly. "The art of biography rests in selection, and what you omit may be as significant as what you include. This biography gives the impression of omitting nothing....The biographer's own comments are always jejune or banal."

As for Stout, Symons faulted the Nero Wolfe creator for being unwilling to put his soul into his detective novels. "At the risk of outraging an accepted American myth," lectured Symons,

|

| Julian Symons (1912-1994) |

I have devoted a lot of my life now to writing about the people who wrote mystery and crime fiction, but I am a historian by training and have always tried to be a historian first and a "literary critic," if I indeed am one, second. Taste is such a subjective matter that I often have shied in the past from making grand pronouncements beginning with words like "It must be said" and "The truth is." I have found over the decades that the more I have read of mystery and crime fiction, the more catholic and generous my tastes have become. The restrictive dogmatism of the Julian Symonses and the Jacques Barzuns I have increasingly abandoned, though it's interesting to write about it, as I am doing here now.

Certainly Julian Symons brought his own personal biases to bear on his assessment of Rex Stout. (As for the McAleer biography, I will allow, as someone who has written biography myself, that I wish McAleer, an astoundingly proficient pack rat, had been more selective of the detail in his book--however he won an Edgar and I haven't, so there is that.)

As someone who himself never in his crime fiction created a memorable series character (and I say this as someone who enjoys Symons' crime fiction), Symons believed that the commitment to an outsize Great Detective as series sleuth, whether it be Nero Wolfe, Hercule Poirot, Ellery Queen, Albert Campion or Gideon Fell, throttled originality in mystery fiction and kept it from developing into something more akin to mainstream literature. Thus in his view Rex Stout had surrendered his considerable talent as a serious writer to a fundamentally superficial endeavor, even if yielded a character, Nero Wolfe, who would be "remembered as long as people read crime stories." Paradoxically, Wolfe was an unforgettable character who appeared in mostly forgettable stories (at least after 1950).

The truth is (as Symons would say), though I can only speak for myself, I don't find the Wolfe stories generally forgettable, even if they do lack, like most everything under the sun, the "metronomic precision of Ellery Queen" (for some that might be a good thing). Again generally speaking, I don't find the stories forgettable before 1950 or after 1950, to use Symons' somewhat arbitrary cutoff point. (It won't surprise Wolfe fans to learn that Symons really liked Stout's Arnold Zeck saga.)

Indeed, although my favorite Wolfe novel was published before 1940, I find the fecundity of and overall quality of Stout's production in the two decades between 1946 and 1966 astonishing and I personally favor this latter period of his writing as a whole. I don't believe, as Symons declares in Bloody Murder, that after 1950 Stout stopped caring about his characters. The carefully planned culmination of the Wolfe saga in A Family Affair (1975), for example, would suggest otherwise.

|

| Before he died, Rex Stout saw that Nero Wolfe had entered the pantheon of Fiction's Great Detectives |

What's the more memorable book from 1957: Stout's If Death Ever Slept or Symons' deliberately drab and dreary The Colour of Murder, which won the Gold Dagger from the British CWA for that year? (Crime writers' awards groups love all things drab and dreary.)

I know what my pick would be, but that's subjective. All I can say--and it must be said--is that I'm pretty confident more people would choose Stout's novel, even with the recent advocacy of the latter work by the British Library's vintage crime fiction reprint series and its distinguished editor, a great admirer of Symons.

But enough with my opinions! What interests me here is the opinion of Mary Stewart. She took two weeks to get back to Prefessor McAleer with a letter, but when she did, gracious, did she rain down hellfire and brimstone on the head of Julian Symons. If McAleer ever read Stewart's letter aloud, Symons ears surely would have burned.

Stewart urged McAleer to "try to forget" that "silly Julian Symons' article." He knew, and the public knew, Stewart assured him, that he had written a good book. Yet she spent more time defending Stout's reputation and assailing that of Symons:

You also know that Rex Stout is an incomparably better writer than the pathetic and jealous Symons (or any of the grubby merchants he admires), and that this [jealousy] is the motivation of the review....It is typical of the man that he singles out Rex Stout's "sexy" novels as "among the best." I only read one of them, How Like a God, and it was not in the same street as The Doorbell Rang and A Family Affair, or indeed any of the lucidly-written, mature works. It is also nonsense to say that his style was not comparable to, say, Ross Macdonald. To my eye and ear, RM's style is derivative, strained and totally predictable. I can feel him trying. Rex Stout's style was--is--flawless.

....do, please, ignore the man's opinions, even if you can't quite ignore his spite. I have met him; he is a boor, and a second-rate writer, and has no sense of style--I mean, he would not know good English if he saw it. The biggest compliment Julian Symons can pay to any book is to dislike it.

....Believe me, everyone I know rates the wretched little man as I do. Forget him. You did a good job. Have a happy Christmas.

|

| a good murder never goes out of fashion |

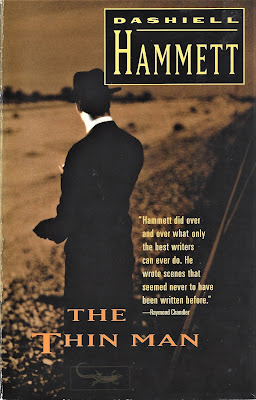

Symons had something of an aversion to the works of genteel lady mystery writers, whether British or American (excepting Agatha Christie, whose puzzle crafting ability he admired), while Stewart expressed disdain for the "grubby merchants" (one suspects the hard-boiled boys) whom Symons admired. If one can but take a broader view and free oneself of one's partialities, one might say that there is merit to go around. Hammett, Chandler, Macdonald and Stout all were fine stylists--and as for Symons and Stewart, well, in coming days I will have something more to say about them.

Note: The Julian Symons review and the Mary Stewart letter both can be found here, though I arrived at them independently several years ago. Other people came to Stout's defense against Symons's critique, and several letters were published in the New York Times. I quote from them here.