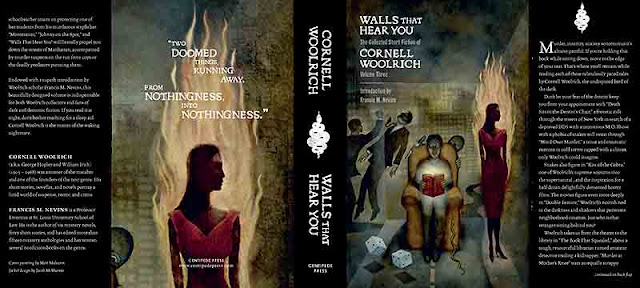

Centipede Press is still going full bore with its remarkably attractive, high-end reissues of Cornell Woolrich volumes. They have reprinted the great American crime writer's six "Black" novels as well as his William Irish novels Phantom Lady, Deadline at Dawn, Waltz into Darkness and I Married a Dead Man and four volumes of short fiction: Dark Melody of Madness (a collection of supernatural tales), Speak to Me of Death (reviewed by me seven years ago here), Stories to be Whispered and, most recently from this year, Walls That Hear You. (Woolrich's two George Hopley novels, Night Has a Thousand Eyes and Fright, and his last Irish novel, Strangler's Serenade, have not yet been reissued by CP.)

Cornell Woolrich has the reputation for being the bleakest of crime writers, both in terms of what he wrote and how he actually lived, and there's certainly a lot to that. Certainly too that's the view stressed in the introduction to this new Centipede volume, where Francis Nevins hits all the usual black notes which he has stressed (and stressed) for decades now about how miserable Woolrich was, primarily because he was, Nevins believes, a "self-hating homosexual" filled with, yes, "homosexual self-contempt." Or as he bluntly put it again, Sam, over at Mystery*File in 2010: "Woolrich was perhaps the most deeply closeted, self-hating homosexual male author that ever lived."

Indeed, it seems that Woolrich was so deeply closeted that he left no actual evidence that we know of that he was gay, self-hating or not! (No one today can say whether the infamous purported Woolrich sex diary ever really existed.) The truth is that it is Nevins who has interpreted Woolrich this way, the gay part coming from hearsay evidence from two elderly women he interviewed back in the 1970s and the self-hating part from his own inferences. He also has written about Milton Propper and Patricia Highsmith as self-hating homosexuals, so it seems to be the theme with him when looking at queer crime writers.

However, we don't actually know whether Woolrich really was gay and while he well may have had contempt for himself, we don't know whether or not this feeling was motivated by homosexuality (if he was really gay). Woolrich, to be honest, had a lot of issues, as they say, stemming in my view both from inheritance and a dysfunctional childhood upbringing which produced in him extreme social anxiety. He had trouble dealing with with people generally, putting aside the matter of his own sexuality.

I've written an 11,000 word essay on the writer based on my own original research, which is shortly to be published elsewhere, and in it I take considerable issue with how the episode of Woolrich's short-lived, unhappy marriage has been portrayed in the vintage mystery media. I hope the piece may prompt us to take a more nuanced and sympathetic look at the author than what has usually been the case, regrettably. That Woolrich's story for decades has been held firmly in the hands of someone who so evidently holds him in contempt as a person (though he loves his writing) is an irony which the mordant author himself likely would have keenly felt.

But enough about that, how are the stories (really mostly pulp novelettes, a form of which Woolrich was a master) which have been collected in Walls That Hear You? Well, there are seventeen of them here and I really liked about eight of them so I suppose you can say we are batting fifty-fifty. It's not as good a collection as Speak to Me of Death in my view, but still pretty good.

It opens up with Woolrich's first published piece of short crime fiction, "Death Sits in the Dentist's Chair," published when Woolrich was thirty years old, way back in 1934 in Detective Fiction Weekly. It's been collected several times before, but it's a fun story, well worth reading again.

Fun I say? Cornell Woolrich fun? Well, in a grisly sort of way, yes. It's about a devilish murder conducted by a diabolical dentist and there's genuine detection in it, of the Wills Crofts/Austin Freeman sort, and a good suspense passage at the end. Yes, there is some Thirties social consciousness in it, an awareness of the problems of poor ethnic minorities (although it's also a necessary plot device). But really it's a clever gadgety murder tale of the sort that John Rhode might have constructed. It also uses the suspense devices of the wrong accused man and the friend trying to help him, which you often see in later Woolrich stories.

The title story, "Walls That Hear You," is another one, very pulpy and lurid, which I have to admit was a bit much for me. (It involves a man who has his fingers and tongue removed but still lives--no thanks!) Equally wild is "Kiss of the Cobra." We are a long way off from noir here and more in purple pulps land, where the words may turn your stomach but they certainly won't break the heart.

"Hot Water," published in Argosy in 1935, is more in the hard-boiled vein, about the kidnapping of an actress at a gambling den in a Mexican town across the border from California. Despite being about crime and violence there's a rather humorous edge to it and it's cleverly plotted and quite entertaining indeed.

|

| nightmarish nights and daze |

We're in more noirish territory with "Johnny on the Spot," about a girl who will do anything to rescue her man from gangsters. It's both tender and tough, with true love and some really nasty scenes of violence, which I suppose Nevins would attribute to Woolrich's "homosexuals' self-contempt" even though it's the sort of thing you get in hard-boiled tales.

"Double Feature" is one of Woolrich's better-known tales, about what happens when a cop out on a date with his girl at the movie theater realizes they are sitting next to a "most wanted" criminal. It's a great suspenser, crying out to be televised, but rather less noirish that "Johnny on the Spot."

"One and a Half Murders" is about a superannuated private detective who investigates on his own dime when his nephew is arrested for a murder he didn't commit. The prevailing tone here is a bit humorous (the retired detective wanting to prove he's still got it), but when he finally resorts to terrorizing the guilty party to get his confession from the real murderer it's not very funny to me.

Nevins thinks this reflects Woolrich's bleak world view, but again it's the sort of thing you see in a lot of crime fiction from that era, when crime writers tended to look sympathetically on private individuals taking the law into their own hands. Many of us still feel this way today. (Look at the reaction to "hero" Kyle Rittenhouse, for example.)

Woolrich's famous tale "Momentum" appears here as well and this is authentic bleak Woolrich, about how murder, Macbeth-like, dreadfully accumulates. The protagonist has sympathetic qualities, but makes a series of disastrous choices, and it's all very dark, much more so that most of the stories in this collection. The story was televised as an Alfred Hitchcock Presents episode that somehow utterly failed to capture its power.

"Mind Over Murder," about a woman living in the tropics who comes up with a plot to frighten her hated husband to death, is really nasty and a corrosive portrait indeed of a marriage. Perhaps Woolrich was looking back on his own! This feels more like a Roald Dahl or John Collier piece.

Then there are my favorites in this collection, "The Book That Squealed" and "The Penny-a-Worder."

|

| A librarian throws the book at criminals and finds love too in one of Cornell Woolrich's most heartwarming tales, "The Book That Squealed" (1939) Yes, I said heartwarming. |

I first read the former in the anthology Women Sleuths, which Bill Pronzini and Martin Greenberg co-edited. "Squealed" features an intrepid librarian (naturally!) as amateur detective who ends up investigating crime by herself when the police don't take her concerns seriously. How she cottons on to the crime is really ingenious. It recalls Agatha Christie's Postern of Fate, oddly enough, except that it is much cleverer and, well, coherent. Let's face it, Postern was not Agatha's greatest moment.

There are some very nasty criminals indeed in "Squealed," but really the whole thing is not far removed from the world of the British crime story from that era. It makes one realize that Woolrich really could have written what we think of as British-style manners mysteries, and probably would have had he grown up in England.

There are a couple of stories here which are very similar indeed to "Squealed." "Murder at Mother's Knee" features a schoolteacher as amateur detective and is an obvious reworking of "Squealed." (The former was published two years after the latter.) Authors often repeat devices in their work but here Woolrich essentially published the same story twice under different titles, though "Squealed" is the cleverer and more charming of the two. "The Body in Grant's Tomb" features as narrator and detective a spinster aunt of the sort associated with Mary Roberts Rinehart's Had-I-But-Known school. She's portrayed well but the plot itself kind of just peters out uninterestingly. When you wrote as much as Woolrich did, you're going to have some comparative duds.

For me the best story in the collection, "The Penny-a-Worder," is not even a genuine crime story, but it is a brilliant little tale about a pulp crime writer. Francis Nevins, who is convinced that Woolrich had no sense of humor, appreciates the fine quality of this story, but somehow himself apparently doesn't see the humor in it. (You would have to have a sense of humor, I think, to see it.) I've written about this story before here, but I think I will write about it again in a successor blog post. It's such a brilliant little story that shows a lot of witty self-awareness on the part of an author whom a lot of people seem to think had capacity only for myopic misery.

Indeed the misery level in Woolrich's pulp fiction generally has been somewhat overrated. Many of the stories in this collection even have-gasp!--happy endings, if not without some considerable bruising for our protagonists along the way. Perhaps this simply reflects the popular medium for which Woolrich was writing here (Thirties and Forties pulps, primarily)--or perhaps the author wasn't quite as relentlessly gloomy as people think.

I'm 66 and I wonder if this self hating homosexual nonsense will ever end. How many self hating heterosexuals are there, and what the heck does it have to do with what people write? This seems a little like the current insistence that only an actor of the appropriate ethnicity/sexual orientation can play a part. It seems to somewhat negate the reason that many people become actors in the first place. Oh well, Woolrich still a genius, Francis Nevins still not a genius.

ReplyDeleteIts been kept up for a long time in Woolrich’s case. Whats frustrating to me is that we have no actual evidence from the author himself, yet people state categorically that he was a “self-hating gay.” Its like people feeling certain that Edgar Hoover was a transvestite. Nevins has convinced himself, but theres no need for the rest of us to go along with him.

DeleteI've come across your blog multiple times, but never bothered to comment before, but I just wanted to (finally) drop a line to say that it's always interesting to read your Woolrich content. (I discovered Woolrich rather by accident at the age of thirteen, when I read I Married a Dead Man, and--since giving it a reread in 2020--have slowly been working my way through more of his writing, short stories and all.)

ReplyDeleteIt's exciting to see him getting something of a revival when it comes to recent reprints, and I can only hope it might lead to some new takes on his work/life. (For instance, I would personally love some good feministic analyses of his stuff, as I think he writes women really well, and he overall strikes me as less misogynistic than a lot of his male contemporaries.) While I appreciate Nevins' efforts over the decades to keep his writing from being completely forgotten, it's also extremely frustrating to see that his take on Woolrich's sexuality has--seemingly--never really been challenged, just echoed over and over again as ABSOLUTE FACT, instead of as the theory that it actually is. At the very least, as you alluded to, it does seem awfully reductive, if not outright offensive these days, to assume that any self-loathing he might have felt must have been related to his sexuality--whether he was gay or anything else.

Anyway, suffice it to say, I'm curious as hell about your upcoming Woolrich essay, and definitely look forward to it!

Well, I agree with all your points, as you will see at greater length in the article, which will appear in tomorrow. I'll post a link.

DeleteAs late in 2021, in the Eddie Muller intro to the attractive Mysterious Press edition of Bride Wore Black, it's stated that due to Nevins' research we "know...that Woolwich was a self loathing gay men." Of course we don't "know" anything of the sort even though people keep saying it.

Nevins "research" on this point consists of retailing hearsay info he gleaned from two interviews with old women about events from long ago. This hasn't established that Woolrich was gay, nor did anyone even say that Woolrich loathed himself on account of his supposed homosexuality, except Nevins. Woolrich may have loathed himself (obviously he had lots of negative thoughts), but that this was on account of his supposed homosexuality is Nevins' own view.

And Nevins seriously failed to perceived how Woolrich's wife subjected him to terrific national humiliation in the newspapers. She didn't accuse him of being gay, just a eunuch essentially. It's hard for me to believe that he missed the magnitude of this. I think Woolrich's wife was not exactly the beatific innocent he makes her out to be.

I think Woolrich often does have interesting women characters and can write very well from a woman's POV. Which doesn't make one gay! He wrote well from men's POV too. My own personal view is that Woolrich was asexual or very low sex drive. I have real trouble with the sailor suit cruising story as you will see! I hope my article gets people to take a fresh look at Cornell. And thanks!

By the way, it must have been very interesting to read Woolrich at 13! I was much older than than when I started reading him, though like many I was exposed to him unwittingly long before that through films and television.

DeleteLooking back, it was definitely an odd thing to read at the age of thirteen, that's for sure! That said, it did stick with me (to the extent that I ended up rereading the book a few years later, when I was 16-17).

DeleteI'm tempted to say more, but I think I'll just wait until your article gets posted. :)

Coming out on Monday now. The article, I mean!

Delete